Baby Born with Itty, Bitty Tooth … Which a Dentist Promptly Pulled

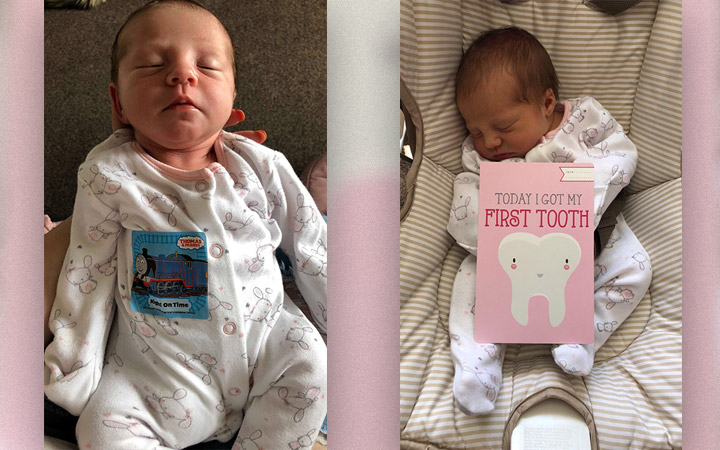

A newborn in England surprised her parents — and her doctors — when they saw that the infant was born with a tiny tooth, according to news reports.

The tooth was wobbly, so when little Isla-Rose Heasman was just 12 days old, her mother took her to a dentist, who put numbing cream on the baby's gum and promptly pulled the tooth out, the BBC reported.

While Isla-Rose's case is rare, the condition, known as a natal tooth, isn't unheard of, said Dr. Homa Amini, a professor of clinical pediatric dentistry at The Ohio State University College of Dentistry, who wasn't involved with Isla-Rose's case. [Chew on This: 8 Foods for Healthy Teeth]

A natal tooth is simply a baby tooth that erupts "very early," Amini told Live Science. But the phenomenon is a bit of a mystery to doctors. "It's really not known why it erupts that early," Amini noted.

Natal teeth happen in only about 1 in 2,500 births, said Amini, who is also a pediatric dentist at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. In about 15 percent of cases, the baby's parents, siblings or close relatives also had a natal tooth, indicating that genetics plays a role, according to a 2012 review on natal teeth in the Indian Journal of Dentistry.

Most babies get their primary teeth, often the lower front teeth, beginning at 6 months of age, an event that "brings immense joy to the parents," the review's authors said. Natal teeth, however, aren't always seen so favorably. These teeth usually have little to no roots, so they're often wobbly and pose a risk to the child, who can mistakenly inhale or swallow the teeth. These teeth can also make breastfeeding difficult and can cut the baby's tongue.

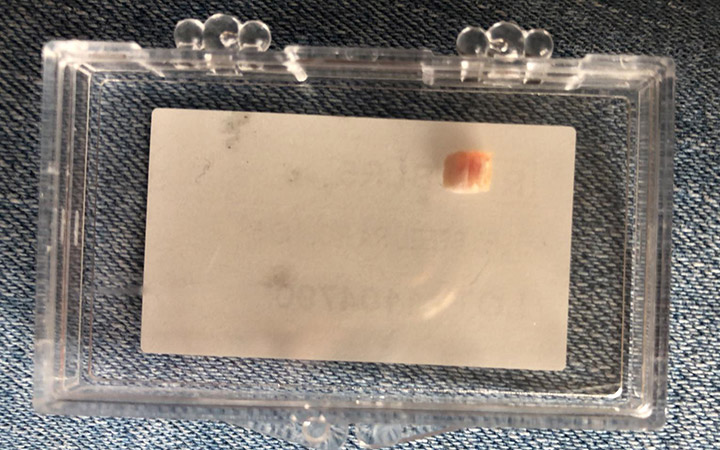

In addition, these teeth are usually not pearly white. "The enamel in natal and neonatal teeth is normal for the age of the child," the review said. "But when the tooth erupts prematurely, the uncalcified enamel matrix wears off because mineralization is not complete. The tooth turns yellow-brown, and the enamel continuously breaks down."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So, doctors usually recommend that the tooth be pulled, just as it was in Isla-Rose's case. When this happens, the child won't grow another tooth in that spot until an adult tooth erupts, usually at age 6 or 7, Amini said.

But even though the child will miss this tooth for a few years, "it's not a problem. They just don't have a tooth down there," Amini told Live Science. "Nothing has been reported as causing long-term problems."

If natal and neonatal teeth are secure enough to stay (and if they're not causing any problems with nursing), they usually remain about 0.07 inches to 0.2 inches (2 to 5 millimeters) shorter than other baby teeth, according to the review.

Historically, natal teeth were seen either as lucky or ill-fated. The Roman historian Titus Livius (born 59 B.C) viewed natal teeth as a "prediction of disastrous events," while Pliny the Elder (born A.D. 23) thought "a splendid future awaited male infants with natal teeth, whereas the same phenomenon was a bad omen for girls," according to the review.

In the past, people in England thought that infants with natal teeth were destined to be famous soldiers, and France and Italy also considered the teeth a mark of good fortune. But in China, Poland, India and Africa, newborns with teeth were usually considered "monsters and bearers of misfortune," the review reported.

These days, whenever a baby's tooth comes in, it's important to take the child to the dentist. That way, parents can learn the best way to care for their baby's little chompers, Amini said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.