Sexy Sea Worms Light Up Bermuda in One-of-a-Kind Mating Ritual

Oct. 12, 1492, is remembered in North America as the fateful day an Italian explorer named Christopher Columbus made landfall in the so-called New World. By some accounts, it should also be remembered as the day he and his crew almost crashed a glowing marine worm orgy.

It happened in the wee hours between Oct. 11 and 12. Columbus stood on the deck of his ship, the Santa Maria, peering into the Caribbean darkness, when he saw a faint, flickering glow far out on the inky ocean. In his diaries, he described the glow as "like the light of a wax candle moving up and down," though it appeared too small and disappeared too quickly to be a sign of land.

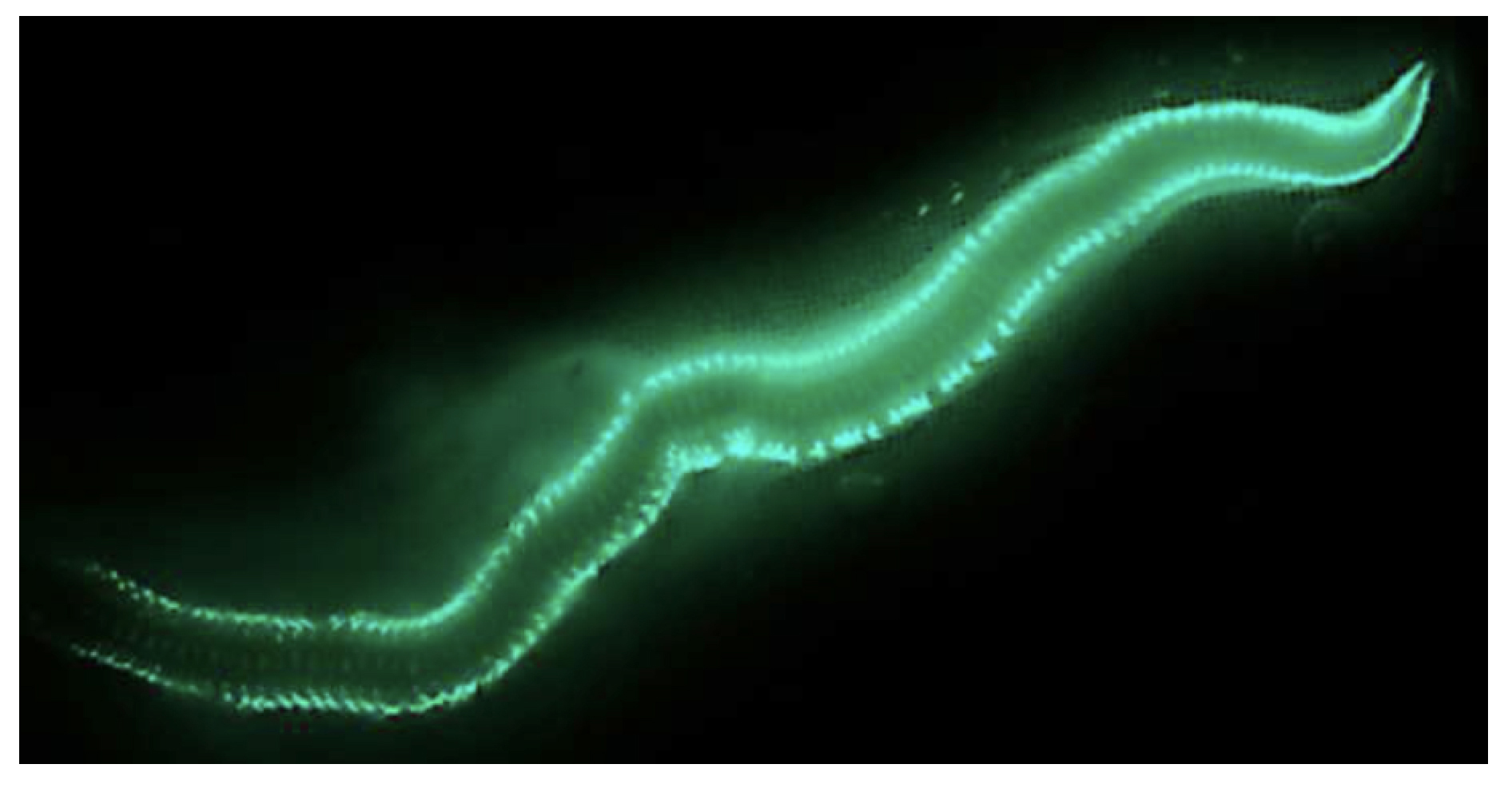

Columbus didn't have much time to study the mystery; a few hours later, his fleet landed at the island now known as San Salvador, in the Bahamas. Today, however, many biologists suspect that Columbus may have been a lucky witness to one of nature's stranger romantic wonders: the massive, green-glowing mating ritual of the Bermuda fireworm (Odontosyllisenopla). Now, a new fireworm study published today (Aug. 8) in the journal PLOS One dives deeper into the chemical processes that make this glowing lovefest possible. [The 7 Weirdest Glow-in-the-Dark Creatures]

Bermuda fireworms are tiny (less than 1 inch, or 2.5 centimeters, long) sea dwellers who live throughout the Caribbean. They're not much to look at on any given day, but catch them at the right moment — approximately 22 minutes after sunset on the third night after a full moon in late summer — and you will see a display of bioluminescence like no other. Here's how Mark Siddall, co-author of the new study, describes the ritual:

"The female worms come up from the bottom [of the sea] and swim quickly in tight little circles as they glow, which looks like a field of little cerulean stars across the surface of jet black water," Siddall, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) Division of Invertebrate Zoology, said in a statement. "Then the males, homing in on the light of the females, come streaking up from the bottom like comets — they luminesce, too. There's a little explosion of light as both dump their gametes in the water."

We know what you're thinking: That's hot. But it's also very peculiar, even among the odd sliver of animals who use chemically generated light to send messages to friends and foes in their ecosystem. What causes this lovely luminescence, and why is it so neatly linked to the full summer moon? Siddall and his colleagues at the AMNH thought about questions like these as they studied the gene expression in three female fireworms plucked from Bermuda amid a mating swarm.

You're positively glowing, my dear

The researchers found that the Bermuda fireworm's signature glow can be traced to a special type of enzyme called luciferase that activates during the mating cycle. Other bioluminescent creatures, such as fireflies, produce luciferase to glow, but the precise variety of luciferase enzyme found in the fireworm has never been detected in any other species, the researchers wrote. This finding not only helps researchers better understand the worm's uniqueness, but may also prove helpful in biomedical research that requires lighting up certain molecules under certain conditions.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's particularly exciting to find a new luciferase because if you can get things to light up under particular circumstances, that can be really useful for tagging molecules for biomedical research," co-author Michael Tessler, a postdoctoral fellow in the Museum's Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, said in the statement.

The team also detected genes that caused the female fireworms to undergo a series of temporary biological changes during the mating cycle. Certain enzymes caused each of the worms' four eyes to enlarge (making them more sensitive to the greenish-blue glow), while others modified the worms' nephridia — a kidney-like excretory organ — to store and release gametes. When it's time for the monthly mating swarm, the fireworms literally have to put on their game faces.

Columbus did not know any this, of course (he also did not know that the Americas even existed, or that manatees and mermaids are two different things), but that's probably for the best. Even worms deserve their privacy.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.