Here's How People First Arrived in the New World … Maybe

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Did the first people to inhabit the Americas hug the coast after crossing the Bering Strait or travel farther inland, between two massive ice sheets?

This question has dogged researchers for decades. Now, a review of archaeological, geologic, anthropological and genetic data argues for both, but especially for the latter: It appears that prehistoric humans favored the inland route, although some traveled along the so-called coastal kelp highway later on, the new review says.

But not everyone is convinced this is the case. Some recent studies have suggested that the coastal route was the preferred path. That's because inland conditions were far too harsh until the ice sheets receded, which some research suggests did not happen until after the first settlements in America were founded. [In Images: Ancient Beasts of the Arctic]

Incredible journey

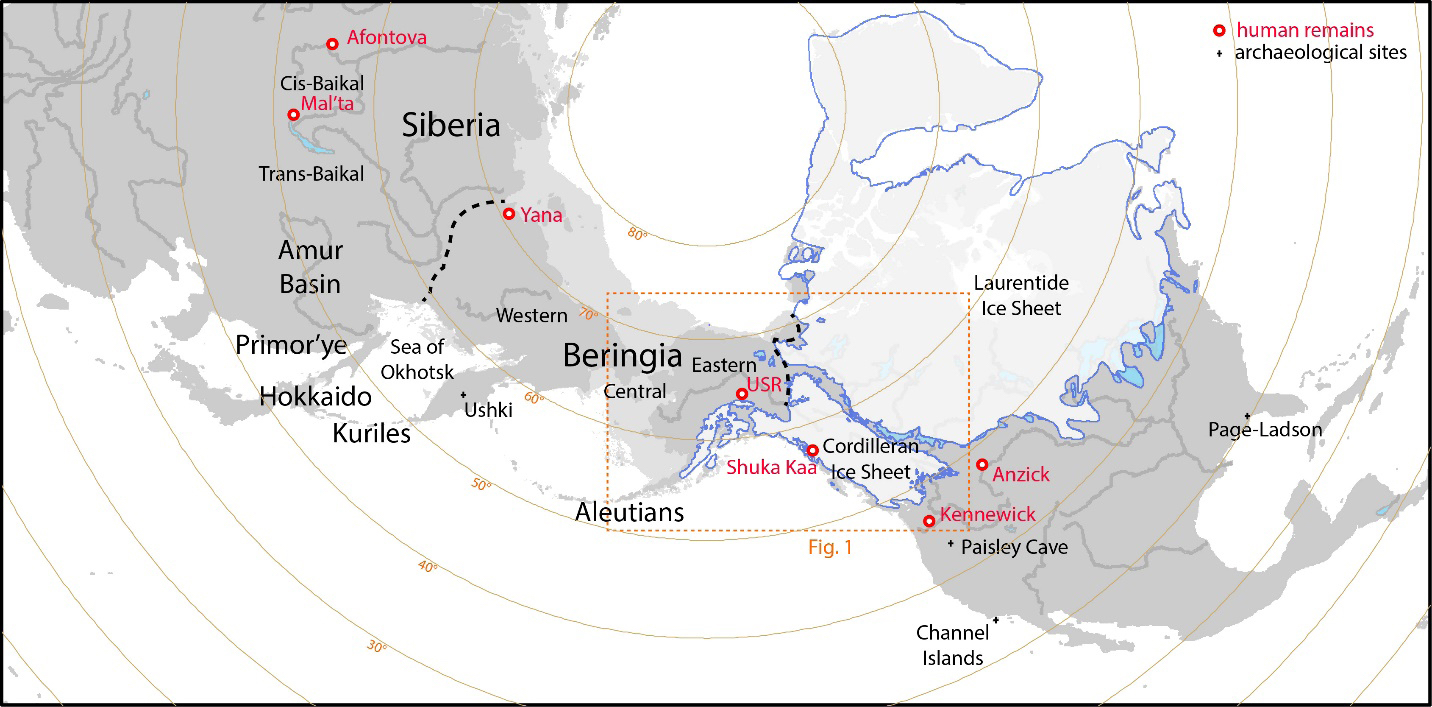

The first Americans began their journey in northeast Asia and southern Siberia. Then, between 25,000 and 20,000 years ago, the ancestors of today's Native Americans split off from East Asians, according to the new review.

What happened next is hotly debated. It's possible that this group immediately traveled across the now-submerged Bering Strait land bridge, or that they hung out in Beringia — a concept known as the Beringia standstill hypothesis. Beringia is the term that describes what then would have been a massive region encompassing parts of Russia, called western Beringia; Alaska, called eastern Beringia; and the ancient land bridge between the two.

The review authors have yet another idea: Maybe this group stayed in northeast Asia, but in a way that led the group to become genetically isolated from other populations there. Then, after they traveled across the land bridge and reached Alaska, the people would have been able to travel inland for the most part through a new ice-free route. (Scientists disagree about when this ice-free route opened, however.)

As the people neared or reached the Americas, their population exploded around 16,000 years ago, said review lead researcher Ben Potter, the department chair and a professor of archaeology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In short, the data show that we've got these Native American ancestors splitting from East Asians quite a long time ago — around 25,000 years ago — with a period of isolation, genetic isolation," Potter said at a news conference. Later, once these people were on their incredible journey, "we see evidence of a population expansion, after 16,000 years ago and before 14,000 years ago, when we see the earliest unequivocal sites in the Americas."

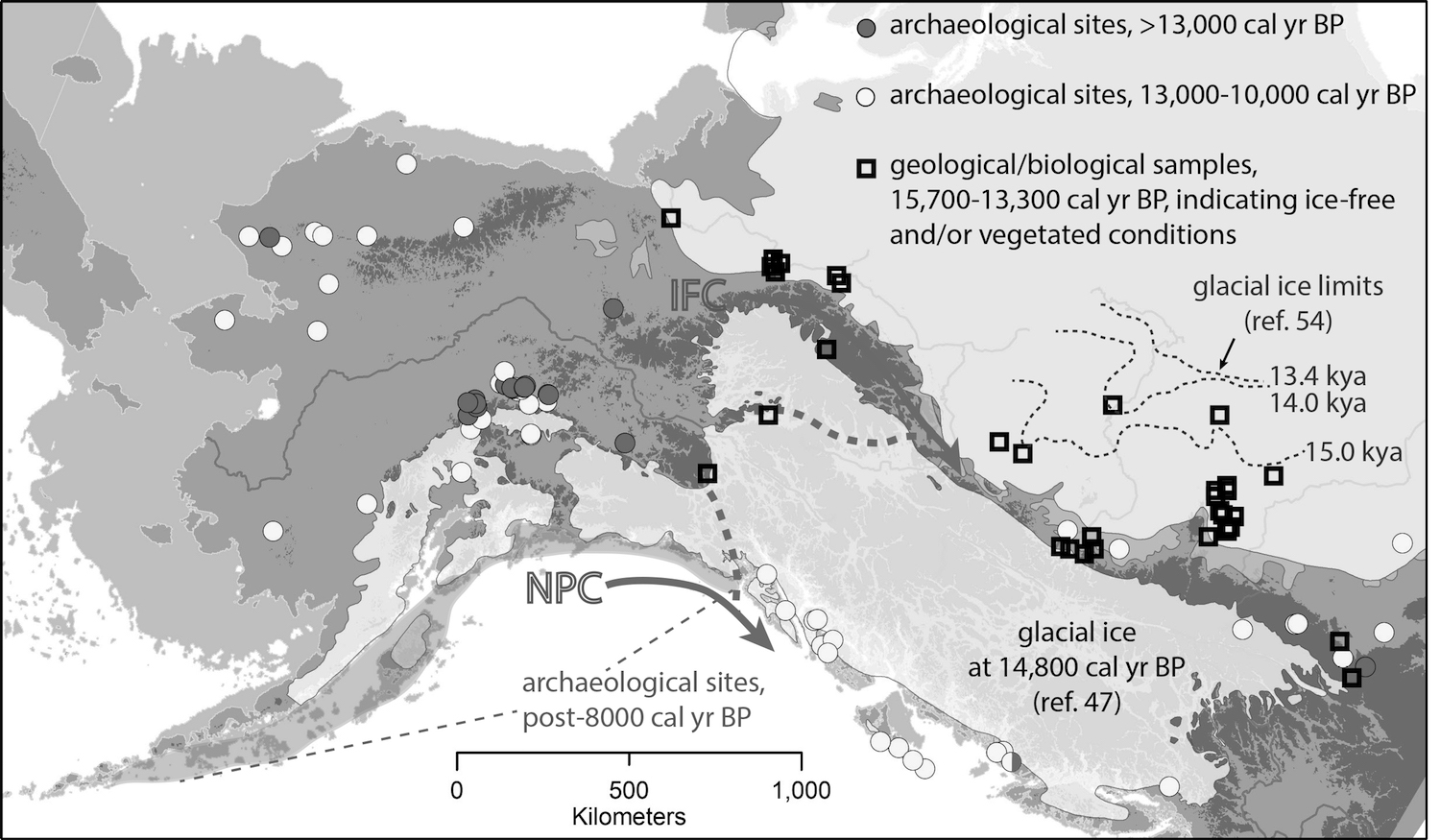

Furthermore, the oldest archaeological sites from the Aleutian Islands to Yakutat Bay, which are now part of Alaska, date to about 8,000 years ago — more than 6,000 years after the dates of the earliest interior Beringian sites, the researchers wrote in the review. This suggests that the first migrants took the inland route, as these sites have older archaeological dates, the researchers said.

Best route

Most archaeologists agree that by 13,000 to 12,600 years ago, the ancient people of the Clovis culture were already living in what is now New Mexico.

But which route did the first Americans take to get there: the inland or coastal corridor? Archaeologists have long debated this issue. For much of the 20th century, scientists thought that ancient people traveled inland, over the ice-free corridor in North America between two massive ice sheets. But over the past two decades, more archaeologists have favored the idea of the coastal kelp highway. That's in part because it's unclear whether the ice-free corridor appeared early enough to fit dates of known archaeological sites in the Americas, and whether this corridor could support a group of migrating humans. [In Photos: New Clovis Site in Sonora]

But newer evidence suggests that the ice-free corridor opened up earlier than researchers previously realized, the review authors said. "The last deglaciated part was ice-free and glacial-lake-free by at least 15,000 years ago," Potter said. "The dates from plant and animal (macrofossils) in the region go back, again, to around 15,000 [years ago]. And I want to emphasize these are minima. The viability of the corridor could be even older; these are just the first actual dates that we have. In any event, these data place the corridor back into contention as a hypothesis for a colonization route."

Other factors also point to an inland route: All of the ancient cultures that these early Americans came from in Siberia and northeast Asia were inland-bound. "They're not coastal; they're not maritime. They were hunting mammoth and bison and horse," Potter said. "The earliest Beringians were doing the same."

Coastal route

While there are a few archaeological sites along the Beringia coast, they are younger than the ones inland, the researchers noted.

Proponents of the coastal-route hypothesis say that many coastal sites that did exist are likely now underwater or didn't survive due to the elements. But Potter and his colleagues argue that large swaths of ice-age coastal land are still above water, and that surveys have failed to find coastal sites older than 12,600 years old, making them about 1,600 years younger than the "earliest unequivocal sites in interior Berginia," the researchers wrote in the review. So, if people took the coastal route that far back, more evidence should have survived.

However, it's also possible that the ancestors of today's Native Americans had a low population density that left behind small sites that either didn't preserve or would be challenging for archaeologists to find, said Justin Tackney, a postdoctoral researcher of anthropology at The University of Kansas who wasn't involved with the review.

In addition, over the past 20 years, some archaeologists have argued that the Clovis people weren't the first culture in the Americas, and that the pre-Clovis existed before them, Tackney said. But the review researchers claim that there weren't many pre-Clovis sites. Rather, they say these sites represent "failed migrations that contributed little genetically or culturally to later Native Americans" or that they were possibly misidentified, and are really the sites of direct Clovis ancestors, Tackney noted. The review also skips some sites that have unreliable dates assigned to them.

"This isn't an unbiased review of the literature, and [people] should be aware of that," Tackney told Live Science. However, the researchers do bring to light "how the archaeological support for the coastal route has weaknesses that need to be explored and explained," he said.

The review was published online yesterday (Aug. 8) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus