Photos: The Power and Beauty of North America's Bighorn Sheep

Iconic animals

The great American West has many symbolic icons, ranging from endless horizons and spectacular sunsets, to the lonely cowboy riding his horse through immeasurable miles of sagebrush and the stately saguaro cactus silhouetted in the light of dusk against the western sky. Yet, arguably another remarkable icon native to North America could be added to this emblematic list — that is the three species of bighorn sheep.

From history

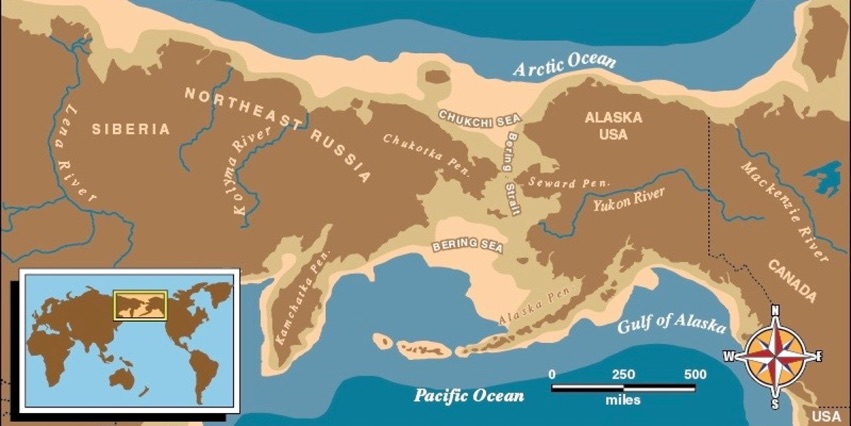

Zoologists believe that the ancestors of the modern bighorn sheep crossed into North America from Siberia using the Bering Land Bridge, shown here, during the Pleistocene epoch some 750,000 years ago. At the time, the Bering Land Bridge was some 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) wide, north to south, and people, flora and fauna, including bighorn sheep, freely moved across it. The bighorn sheep was one of 22 species of mammals, some of which were the musk ox (Ovibos moschatus), grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis), saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica), moose (Alces alces) and woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), that migrated into the Americas from Eurasia.

Family ties

Three distinct species of wild mountain sheep came into North America during this time — the Siberian snow sheep (Ovis nivicola), the Dall sheep (Ovis dalli) and the largest of the wild sheep known as the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis Canadensis). Through the centuries, the Rocky Mountain bighorn spread southward along the mountain ranges into Baja California and the northwestern edge of modern-day Mexico. Zoologists now recognize seven subspecies of bighorn sheep in North America.

Strong and nimble

Male Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep can grow to weigh over 300 pounds (136 kilograms) and stand over 3 feet (1 meter) tall at their shoulders. Females tend to be only half the size of the males. These gregarious animals are most at home in the alpine meadows and grassy mountain slopes, but they never stray far from the protective rocky, rugged cliffs and bluffs. During the warm summer months, they graze at elevations ranging from 6,000 to 8,500 feet (1,829 to 2,591 m), but they frequent elevations between 2,500 and 5,000 feet (762 and 1,524 m) during the cold and snowy winter months.

Family life

Rutting season for the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep lasts from mid-autumn through early winter. Females breed once a year and have a gestation period of between five and six months. Females will find an isolated area to give birth to no more than two lambs. The young lambs quickly learn to walk and follow their mothers along the rocky terrains in which they must learn to successfully navigate. Mothers will nurse their lambs for four to five months. Male bighorn sheep play no role in raising the lambs.

Shows of power

Most unique to bighorn males is the vicious head-to-head combat for breeding dominance that occurs during the rutting season. The horn size of the bighorn rams is a symbol of power and breeding privilege. Dominant males carry horns that weigh upwards of 30 pounds (14 kg). A large male can smash into his opponent at speeds up to 20 mph (32 km/h) with some battles for dominance lasting up to 25 hours. Males do not defend territory and only engage in head butting for mating rights to an estrous female.

Made for the battle

Bighorn sheep have double-layered skulls that help protect the brain from the blows of rutting combat. They also have a series of massive tendons that attach the skull to the backbone and allow the head to recoil as it absorbs the blow from another battling ram. Younger males usually do not rise to mating status until at least 7 years of age.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Quick growth

Within a few weeks of birth, young bighorn sheep form a herd of their own. They seek out their mothers only to suckle; even so they remain nearby their mothers for protection from potential predators. Since bighorn sheep can quickly scale steep mountains with perilous ledges as small as only 2 inches (5 centimeters) wide, they can usually escape the coyotes, mountain lions, golden eagles and bears with which they share their mountain environment.

Adapting to environment

A subspecies of the bighorn sheep family is the desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni). These bighorn sheep have adapted to the arid desert mountain environment and range from the Mojave Desert of Nevada and California, eastward through the Sonoran Desert of Arizona and continue to be found in the Chihuahuan Desert of west Texas and northern Mexico. Desert bighorn sheep tend to have slightly smaller bodies, longer legs and lighter coats than their larger Rocky Mountain bighorn cousins; but the male's massive horns can be just as spectacular.

Evolving to survive

Like all desert animals, the desert bighorn sheep have adapted to their environments lack of free-standing water. They have evolved a nine-stage digestive process that allows for the maximum absorption of both nutrients and moisture from the grasses and other vegetation that they eat. Even with this extremely efficient digestive process, desert bighorn sheep must seek out standing water to drink every two to three days.

Revered creatures

Throughout history, bighorn sheep have played a prominent role in the indigenous cultures of North America. Their ability to survive in some of the West's most inhospitable environments earned them an honorable place in the mythology of Native Americans. Because many native cultures saw the bighorn sheep as a food source, the animals were considered sacred. They were associated with the sky and were often viewed as guardian spirits. They are commonly depicted across the American West on panels of Native American petroglyphs.