Huge Cache of Magma Hidden Beneath California Supervolcano

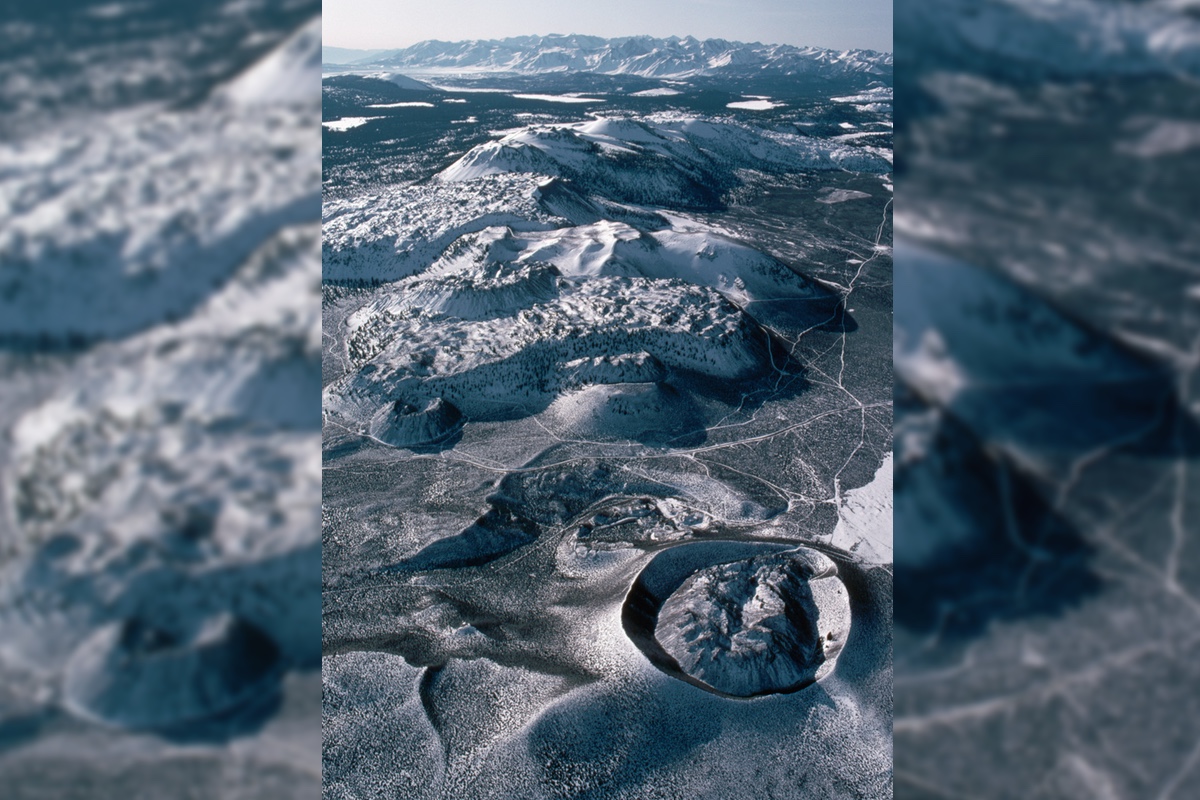

Some 760,000 years ago, before our species took its first steps on Earth, an enormous eruption in what is now eastern California sent high-speed rivers of ash and lava across an area tens of miles across. The event ejected ash as far east as present-day Nebraska.

When the dust settled, six days later, the Long Valley supervolcano had disgorged about 1,400 times the volume of lava, gas and ash as the famous 1980 supereruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington.

And since 1978, Long Valley has shown signs of restlessness, with the depressed valley at the center of the volcano (the caldera) showing uplift, possibly from magma moving toward the surface. (Magma is the hot rock stored beneath a volcano that ultimately erupts onto land and is renamed lava.) Some scientists also argue that liquids from stored magma may be causing the uplift. [The 11 Biggest Volcanic Eruptions in History]

Now, scientists think they've figured out what's happening in the bowels of this beast, finding evidence of a mother lode of magma — some 240 cubic miles (1,000 cubic kilometers) — stored like syrup between the rocks making up a giant stack of "pancakes." That's "enough melt [or magma] to support another supereruption" like the one 760,000 years ago, Ashton Flinders, of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Menlo Park, California, and colleagues wrote online Aug. 2 in the journal Geology.

While the new findings don't solve the mystery of what's causing the recent uplift, they do provide a more detailed picture than ever of Long Valley's magma system, Flinders said.

Beneath the caldera

Until now, studies of Long Valley have fallen into one of two groups: They either imaged small features down to shallow depths (say, down to a few kilometers) or took take images of larger features down to much deeper levels.

"This has left a bit of a shadow zone in the midcrust, where the shallow studies can't see and deeper studies tend to blur anything they do see," Flinders told Live Science. "What we're seeing isn't new. It's just that we're seeing it at this level of detail for the very first time."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To capture that detail, the researchers looked at how ambient noise (the seismic waves that constantly travel through Earth) moved through the area beneath the Long Valley Caldera. "We used physics-based computer simulations to model the way this energy travels through the volcano," he said.

The simulation needed a lot of computer power, so the researchers borrowed time on the supercomputer called Pleiades at NASA's Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California. "To do this research on a single computer like you might have in your home would require that one computer to run for about 22 years," Flinders said.

The resulting 3D image shows quite a trove of partly melted magma beneath the caldera.

But just because there's enough magma for a mega explosion doesn't mean that one is coming, he said.

"While it's impossible to predict when an eruption might occur, we can say that an eruption from Long Valley in our lifetimes is extremely unlikely," Flinders told Live Science.

To be safe, the USGS is monitoring Long Valley and the neighboring Mono-Inyo volcanic chain for any signs of unrest, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.