9 Reasons We Have an Undying Interest in the Undead

We like considering an apocalypse.

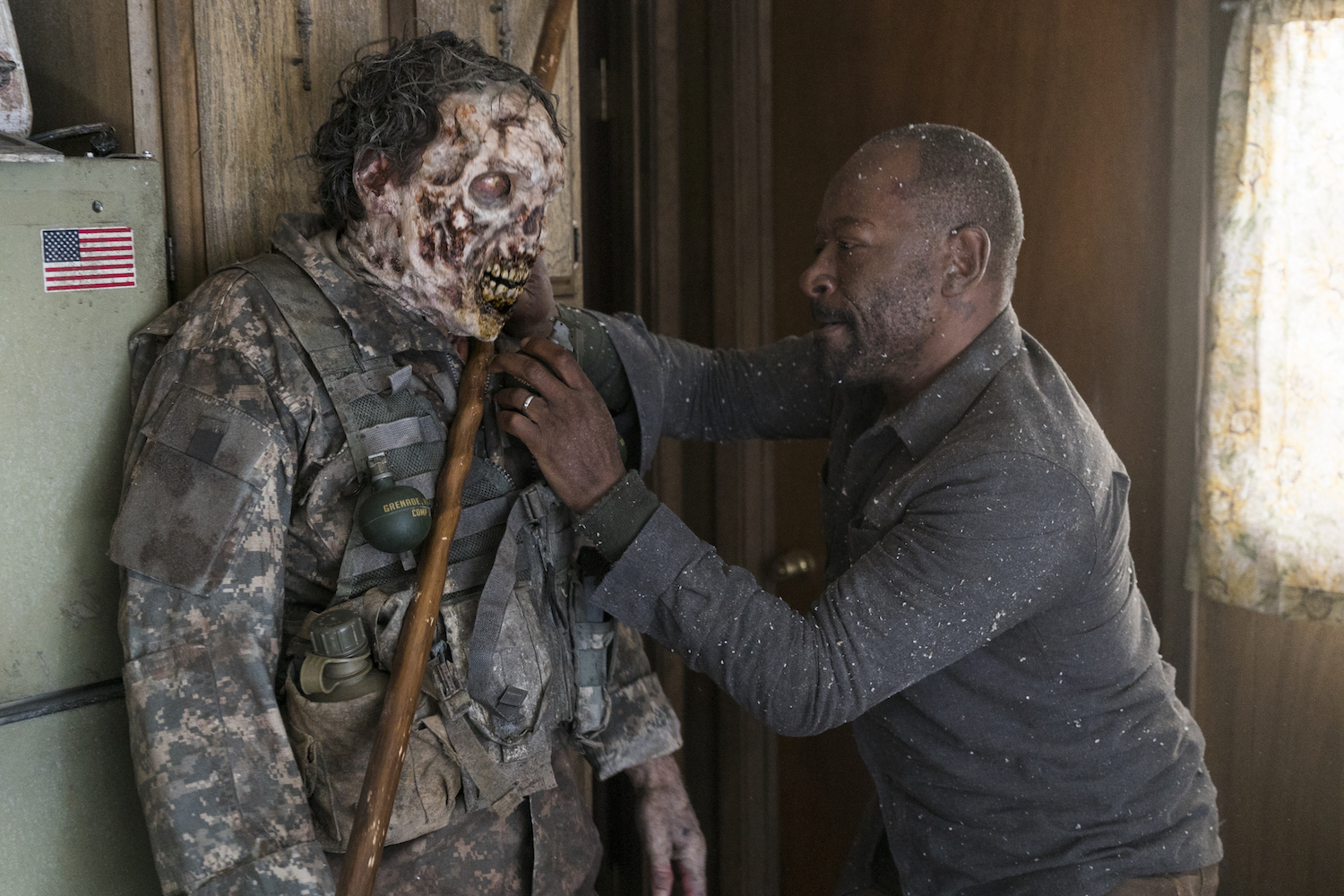

People have been making predictions about the end of times for a very, very long time. They've never been correct, but that doesn't seem to deter modern-day apocalypse forecasters. Live Science previously reported on the growing trend of apocalypticism, and how an increasing number of books, television shows and movies have portrayed postapocalyptic worlds over the past several decades. Among them is AMC's sci-fi series "Fear the Walking Dead" (which airs on Sundays at 9 p.m. EDT/8 p.m. CDT). The show, now in its fourth season, follows characters as they try to survive a zombie-driven apocalypse. [10 Failed Doomsday Predictions]

Zombies are more thrilling than they are terrifying.

Walking-dead humans don't exist, and people know this. They enjoy the scary feelings they get when watching horror shows because they know they aren't really in danger, David Rudd, a psychologist and president of the University of Memphis, previously told Live Science. Because they know the risk of something like a zombie attack is marginal, they experience excitement instead of fear, Rudd said.

Zombies represent a longing to reconnect with humanity.

Humans are naturally good at empathy, but we are bombarded with information from news outlets and technology, which tends to destroy that empathy, especially when it comes to empathy for people outside your personal circle, said P. J. Manney, writer and humanist, in an article she wrote for Live Science. But empathy is restored when people discover things they share, and sometimes that's pain and suffering, Manney said.

In zombie apocalypse stories, people are generally more likely to survive if they seek power in numbers. It's easier to fight off a herd of the walking dead if you have a dozen people by your side. That means you can't disregard other people and face-to-face communication is a necessity — a stark contrast from today's world, in which cellphones and computers allow people to communicate without ever meeting in person.

We're intrigued by the art of survival.

Even if you don't spend your life preparing for the apocalypse, it may have crossed your mind how you might handle things, especially when watching others go through it in a fictional world. After all, the drive to survive is a deeply rooted instinct. Dystopian shows help people work through how they'd act in a survivalist situation, Angela Becerra Vidergar, a literary scholar at Stanford University, said in a statement.

Watching people fight for their lives against zombies "allows the audience to work through some of those difficult, threatening ethical dilemmas, or to think about their own capacity for survival," Vidergar said. "What character would I be like? What would I be willing to do in order to survive?" [7 Perfect Survival Foods]

We're attracted to violence.

Research in mice suggests that the mammalian brain processes aggressive, violent behavior the same way as it does other rewards, Live Science previously reported. "We learned from these experiments that an individual will intentionally seek out an aggressive encounter solely because they experience a rewarding sensation from it," Craig Kennedy, professor of special education and pediatrics at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, told Live Science. And considering that aggression is a highly conserved trait in mammals, it's likely humans crave violence, too, Kennedy said.

We also like fear.

People enjoy watching their greatest fears come to life in a fictional story, Paul Bloom, a psychologist at Yale University, told Big Think. Bloom's theory is that fictional tragedy and imaginary horrors help prepare people for real life by delivering moral truisms. There's not as much to learn from a story about an average person, living an average life and in an average place, Bloom said. [The Anatomy of Fear (Infographic)]

Zombie stories help relieve stress.

The alternate realty of a zombie apocalypse allows people to briefly escape the stress of social pressure and information saturation they encounter in their everyday lives, said Douglas Rushkoff, author of "Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now" (Current, 2014). "People watch zombie shows almost as a dream-come-true," Rushkoff told Business Insider.

"Sounds bad on the surface," Rushkoff said. "But in the zombie apocalypse, there's no Twitter, there's no cellphone, there's no boss, there's no [Internal Revenue Service] IRS." Instead, the only goal is to survive and help the people you care about survive, he said. "It's relaxing on a certain level." [11 Tips to Lower Stress]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's a scary situation we think we could handle.

The zombies in AMC's series "Fear the Walking Dead" are the kind that shuffle along slowly, with limited coordination, and they clearly lack cognitive abilities. They can be deadly, but it's not like a professional fighter coming at you. "We can actually deal with zombies," said Richard Smith, a mathematician at University College Dublin in Ireland who uses zombies to create mathematical models.

Fighting zombies is easier if there's teamwork, Smith previously told Live Science. "If we fight them individually, we're not going to be too effective, because most individuals just aren't good at fighting," said Smith [5 Strange Facts About the Pentagon's Anti-Zombie Plan]

Zombie stories make us feel hopeful.

There are typically at least a few survivors during a zombie apocalypse, and that gives the audience hope that things might work out even in the toughest of times — maybe they'll figure out a way to overcome the zombies! (Of course, if they did, then the thrilling tale would be over.)

Hope is a positive emotion that humans instinctively to want to feel, Helen Fisher, a biological anthropologist wrote previously for Live Science. "Life through rose-colored glasses keeps us healthy, energized and focused on reaching our special goals," she wrote. "We are built to hope."

Kimberly has a bachelor's degree in marine biology from Texas A&M University, a master's degree in biology from Southeastern Louisiana University and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She is a former reference editor for Live Science and Space.com. Her work has appeared in Inside Science, News from Science, the San Jose Mercury and others. Her favorite stories include those about animals and obscurities. A Texas native, Kim now lives in a California redwood forest.