That Massive Black Sarcophagus Contained 3 Inscriptions. Here's What They Mean.

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 9:10 a.m. E.D.T. on Aug. 22, 2018

Three drawings, incised on three sheets of gold, have been discovered in a massive black granite sarcophagus in Alexandria, Egypt.

One expert, not involved with the research, told Live Science that one of the drawings may depict the seed pod of an opium poppy within a shrine. The significance of this enigmatic drawing is still not clear, the expert said. [Photos: Mummies and Figurines Discovered in Luxor]

Black sarcophagus revealed

The black granite sarcophagus, which is 9 feet long, 5 feet wide and 6 feet tall (2.7 by 1.5 by 1.8 meters), became a media sensation after its discovery in Alexandria in early July. When the container was opened, three skeletons and a bunch of sewage were discovered inside the sarcophagus. The age of the sarcophagus is uncertain, but archaeologists believe that it could date back to sometime between 304 B.C. and 30 B.C., a time when the descendants of one of Alexander the Great's generals ruled Egypt.

Over the past month, archaeologists and conservators have been going through the stinky remains, and yesterday (Aug. 19), the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities announced in a statement that the three small sheets, with incised drawings, had been discovered within the sarcophagus. Archaeologists with the ministry did not comment in the statement on what the images show or mean.

Researchers also learned more information about the three skeletons. One came from a woman who was between 20 and 25 years old when she died, while the other two came from men who were in their 30s or 40s at time of their deaths.

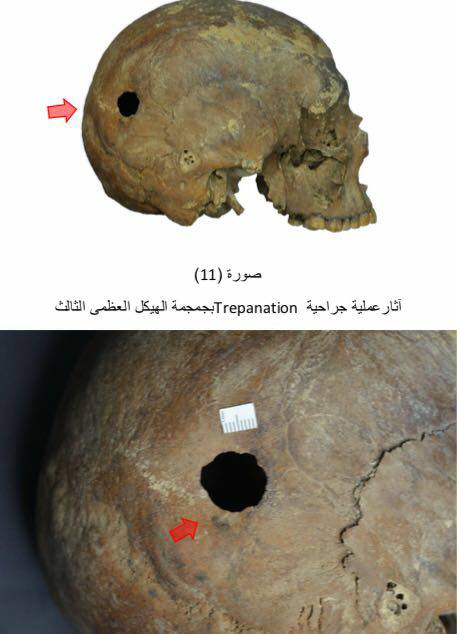

One of the skeletons had a 0.7 inch (1.7 centimeters) hole in the skull, which could mean that the man underwent the surgical intervention called "trepanation," meaning the hole was deliberately drilled, Nadia Kheider, head of the Central Department of Antiquities of Lower Egypt, said in the ministry statement. The procedure was often used in the ancient world, believed to help alleviate a variety of medical problems.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This surgery is the oldest surgical intervention ever known since prehistory but was rare in Egypt," Zeinab Hashish, a skeletal expert who works for the ministry, said in the statement.

Mysterious drawings

Live Science reached out to several experts not affiliated with the research to ask what the drawings found incised on the gold sheets might show and mean.

Few of the researchers were able to respond at time of publication, but one scholar who did was Jack Ogden, the president of the Society of Jewellery Historians. He has conducted an extensive amount of research (including his doctoral thesis) on Egyptian gold jewelry from the period around 2,000 years ago.

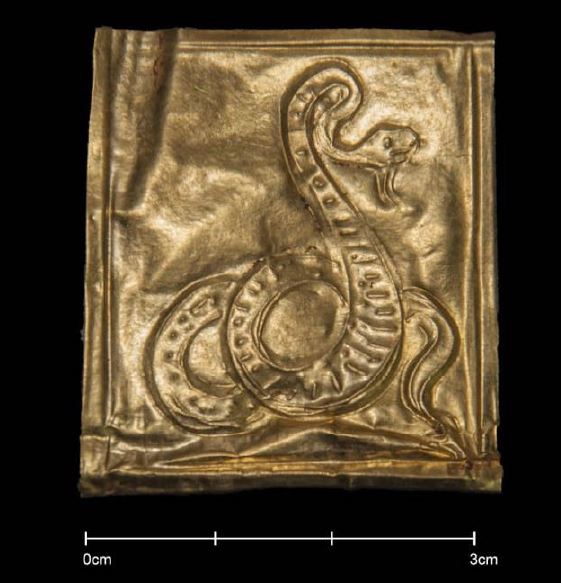

One of the drawings is a snake that doesn't have a hood, Ogden said, noting that this is commonly seen in Egyptian jewelry. Unhooded snakes "had connotations of rebirth — they shed their skin — and thus [are] perfect in a funerary connection," said Ogden. Unhooded snakes "were seemingly connected with the goddess Isis."

"As a rule of thumb, it would seem that snake jewellery was primarily a female thing, but I am not sure whether one could suggest that the presence of a snake here suggests it was connected with the female occupant of the sarcophagus" Ogden said.

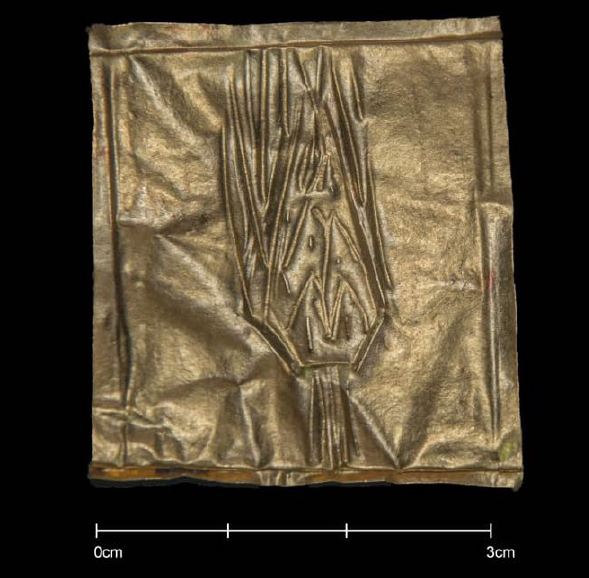

Another drawing shows a palm branch or ear of corn, both of which are common motifs "related to fertility and rebirth," Ogden said.

The most enigmatic drawings show what may be the seed pod of an opium poppy within a shrine, although Ogden emphasized that he cannot be certain what the drawing shows.

"Opium seems to have been quite widely used in Greco-Roman Egypt for medicinal purposes, but there may be some connection — in the ancient mind at least — between its sleep- and dream-inducing qualities and death and rebirth," Ogden said. "It is intriguing."

Additionally, a small gold artifact, whose purpose is unclear, was found in the sarcophagus. Researchers with the ministry did not say in the statement if there are any drawings or inscriptions on it.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the size of the hole in one of the skulls found in the sarcophagus. It was 0.7 inches (1.7 cm) in diameter, not 6.7 inches (17 cm) in diameter.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.