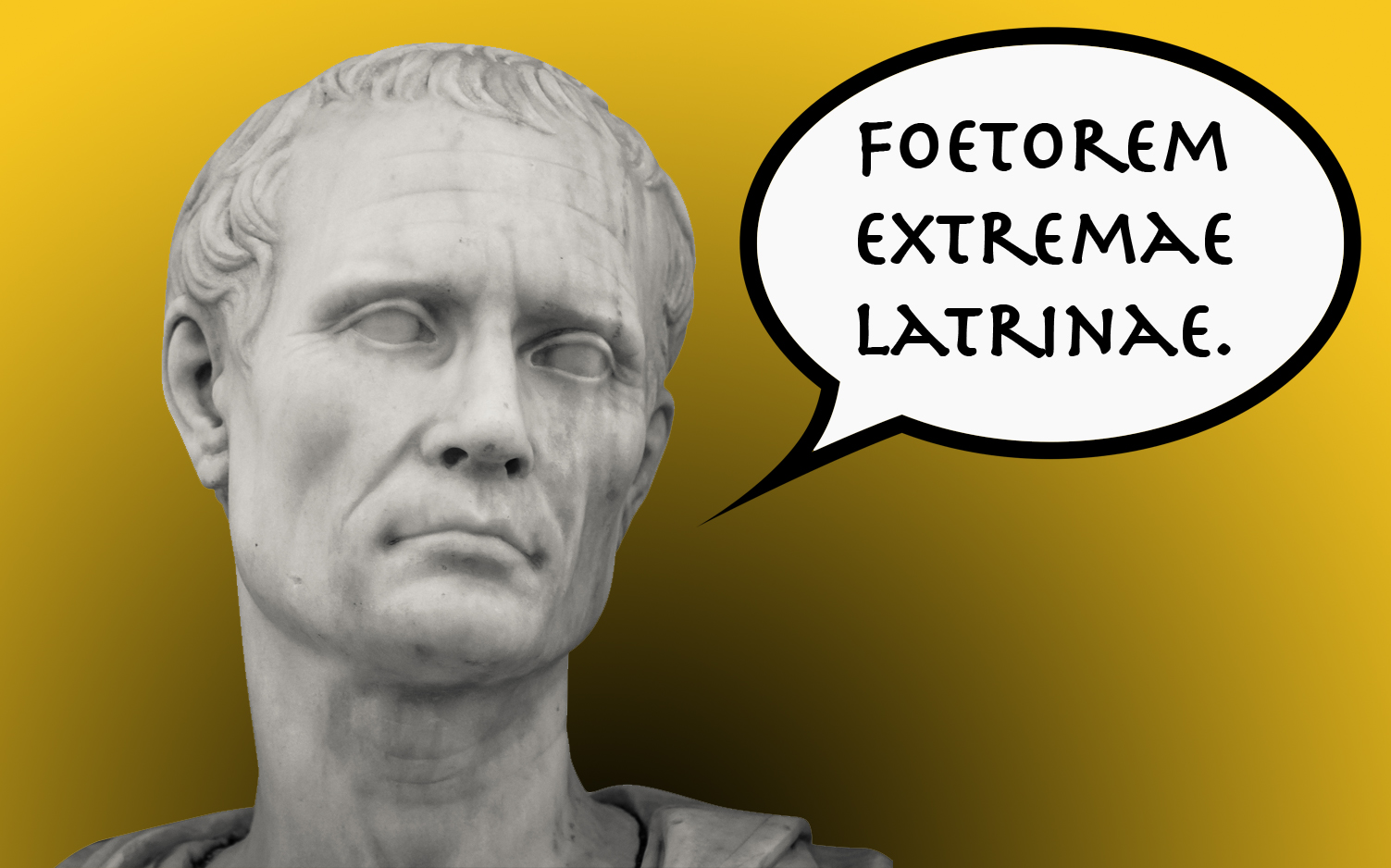

Think Politics Today Is Ugly? Politicians in Ancient Rome Were Insulting, Too

Are ugly accusations and verbal abuse in politics "business as usual"? In recent years, verbal jabs traded between political opponents seem less like discourse between adults, and more like acid-tinged dialogue cut from "Mean Girls" because it was too nasty.

But while such behavior is distasteful and unpleasant, it isn't new — the tradition of politicians indulging in scathing personal insults was widespread across the ancient Roman Republic, and was exquisitely brutal, according to new research.

In fact, Roman leaders frequently traded verbal attacks and flung deeply personal put-downs and scandalous accusations at their opponents. They even endured barrages of insults from the people that they governed, according to Martin Jehne, a professor of ancient history at Technische Universität Dresden in Germany. [Oh Snap: 10 Memorable Political One-Liners]

Jehne will present his findings about insults in ancient Roman politics at the 52nd Meeting of German Historians, taking place at the University of Münster in Germany from Sept. 25 to Sept. 28. The meeting's theme, "Divided Societies," addresses abusive speech and the challenges posed by divisions between social groups from ancient times to the present, according to a conference statement.

According to Jehne, Roman senators used blistering putdowns of an opponent to strengthen their standing among their supporters — a strategy that echoes in today's political arena. Insults then — as now — were used for entertainment value, garnering attention and generating indignation, "similar to insults, threats and hate speech on the Internet today," Jehne said in the statement.

But such a strategy could backfire, if the audience sided with the person on the receiving end of the insults, Jehne told Live Science in an email.

"Insulting in a public context always means to fight for the approval of the audience," he said. "And you never can be sure how people will react."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scathing slander

When it comes to modern-day insults in politics, President Donald Trump is particularly notable, lending belittling nicknames to political figures in the U.S. and on the world stage. He called North Korean leader Kim Jong Un "Little Rocket Man," labeled Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau "dishonest & weak" and mocked Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren by calling her "goofy" and "Pocahontas" (a racist nod to her Native American heritage).

In fact, his roster of monikers — for both Democrats and Republicans — reads like a roll call of rejected names for Disney's seven dwarfs: "Cheatin'," "Lyin'," "Sneaky," "Crazy" and "Crooked" are just the tip of his insult iceberg.

And Roman politicians could be just as savage. Marcus Tullius Cicero, a famed speaker and political figure who lived during the first century B.C., once accused a rival named Clodius of incest with his sisters and his brothers, according to Jehne. Clodius' response — claiming that Cicero was acting like a king — may not sound too terrible by today's standards, but it was a searing slight in the Roman Republic, which shunned pretensions of royalty, Jehne said in the statement.

But as much as Roman senators despised royal airs, they typically came from privileged households, and apprenticeships to older, experienced senators likely taught them how to navigate the political minefield of verbal insults from their peers, Jehne told Live Science.

"They learned how to do the job by observation and imitation. So if they witnessed a harsh argument with insulting parts in it between senators, they also learned how to do that — and how to endure that," he said.

Jeers from the peanut gallery

The politicians of ancient Rome weren't the only ones spewing insults at their fellows. Roman citizens also expressed their displeasure with unpopular figures through public mockery, which was sometimes hurled from the stage, Jehne said.

For example, in 59 B.C., the politician and general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (also known as Pompey), attended a play at a festival for the god Apollo, and the audience and performers used the theater to demonstrate their disapproval of the unpopular leader. When an actor delivered the line, "By our misery, are you great!" the audience turned to look at Pompey and roared with laughter, and insisted that the actor repeat the line, according to Jehne.

The historian Cicero wrote that the actor repeated the line 1,000 times, "which is exaggerated, of course," Jehne said. "But Pompey had to sit there and suffer while the people laughed at him. The whole event was extremely insulting for Pompey and he could not do anything against it."

Different circumstances between the present and the distant past — especially when it comes to politics — make direct comparisons of human behavior across millennia somewhat tricky, Jehne said. However, the persistent use of insults in the political realm does suggest something unpleasant about human nature, he said.

"In our research group in Dresden we rely on the basic assumption that invectivity — our artificial term for the whole complex of insulting, abusing, defaming, discriminating and so on — is a universal feature in human societies," Jehne said.

But even if that's true, people can still decide — as individuals and as communities — when enough is enough. We may not be able to entirely do away with the impulse to be insulting, but humans are still capable of creating boundaries and setting limits, confronting and calling out unacceptable behavior — no matter how high their station, Jehne added.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Scientists built largest brain 'connectome' to date by having a lab mouse watch 'The Matrix' and 'Star Wars'

Archaeologists may have discovered the birthplace of Alexander the Great's grandmother

Elusive neutrinos' mass just got halved — and it could mean physicists are close to solving a major cosmic mystery