Climate Change Could Drastically Change Ecosystems Around the World

For a preview of what's to come for the Earth's ecosystems, look to the past.

In a new study, an international group of researchers analyzed fossil records to track how the planet’s vegetation changed as Earth climbed out of the last ice age thousands of years ago. Then, the scientists used their data to predict how vegetation in the future — and everything dependent on it — will also change. [6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change]

The planet is headed into uncharted territory, with "no analog conditions" in terms of climate, said study co-author Jonathan Overpeck, the dean of the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan. "It makes it a lot harder for us to be sure what's going to happen next."

The fossil records show that the world is very sensitive to temperature changes, which suggests that if fossil fuel emissions continue unabated, accelerated warming could lead to dramatic transformations in vegetation and ecosystems around the globe, the team wrote today (Aug. 30) in the journal Science.

Subsequently, that warming could lead to changes in the amount of carbon that plants can store, the available water supply and the global biodiversity that we depend on not only for a healthy, functioning ecosystem, but also for medicine, food and building materials, Overpeck told Live Science.

From the peak of the last ice age, 21,000 years ago, to the early Holocene epoch — the current geological age — the planet warmed by around 4 to 7 degrees Celsius (7 to 13 degrees Fahrenheit). If greenhouse gases aren't substantially reduced, the magnitude of warming that occurred over the course of 11,000 years following the end of the ice age will happen over a much shorter period: 100 to 150 years.

Rewinding the tape

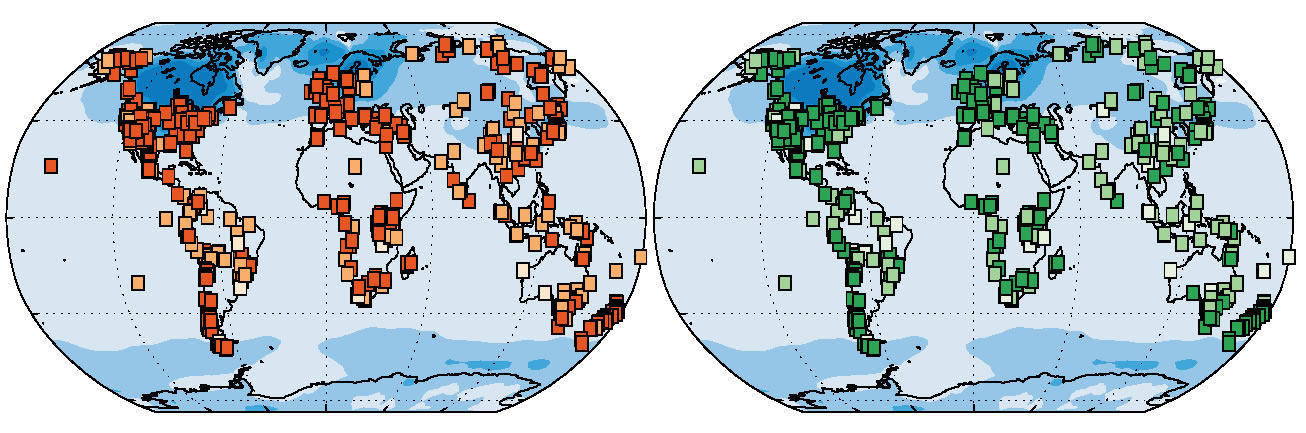

To decipher how plant life changed in the past, the researchers analyzed ancient pollen and plant fossils from nearly 600 sites on every continent except Antarctica. The investigators divided the changes they observed into two categories: compositional changes, or changes in plant species in the area, and large structural changes, like a tundra becoming a forest or a deciduous forest becoming an evergreen forest. The various changes were classified as "large," "moderate" or "low."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, focusing on the sites with moderate or large changes, the scientists further classified the sites, this time addressing the role climate change could have played in the shifts. They used the same scale for the role of climate (low, moderate or large). In other words, the researchers sought to determine whether the large changes were due to climate change or the result of, for example, human activity or large animals.

The researchers found that the warming period after the last ice age played a large role in vegetation changes around the world. Areas that had the greatest temperature changes also tended to be those with the greatest vegetation changes, the study showed.

Indeed, the scientists found that warming temperatures largely changed the composition of the vegetation in 71 percent of the sites around the world and the structure of the vegetation in 67 percent of the sites; rising temperatures moderately changed the composition in another 27 percent of the sites and the structure in 28 percent of the sites.

The changes in plant life were most evident in mid to high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, as well as in southern South America, tropical and temperate southern Africa, the Indo-Pacific region, Australia, New Zealand and other countries in Oceania.

There were also some sites that showed very little compositional or structural change in vegetation, according to the paper. But nearly all sites with low compositional change also experienced low temperature changes.

This shows that our planet is highly sensitive to temperature changes, Overpeck said. Even if we end up curbing fossil fuel emissions and meeting the targets of the Paris Agreement, some change is still inevitable, but it would affect less than half the planet, he said.

In contrast, if we don't meet the Paris targets, "then we'll have much wider change around the planet." And that change will be much bigger and more difficult to predict.

Underestimating change

Peter Verburg, a professor of environmental geography at the University of Amsterdam who was not part of the research, said that it's difficult to extrapolate the study's findings to the present day.

The study was "based on paleo[lithic] conditions, and the present-day vegetation is incomparable [to the vegetation in those conditions] as human activities have changed land cover in some way in about 80 percent of the terrestrial surface," Verburg told Live Science in an email.

"Nevertheless, what we learn is that ecosystems are extremely sensitive to changes in climate," he said.

Indeed, the new study is "another confirmation that climate change will hugely affect the Earth system and the ecosystems we depend on," Verburg said. In other words, it is yet "another call for immediate action."

Overpeck said that the results of this study likely underestimate the change that will happen in the future if we don't curb emissions.

"There are many reasons why these forests are going to have a rougher time [adapting to climate change] in the future than they had in the past," Overpeck said, but perhaps the major reason is that the time frame is sped up so significantly. That makes it a lot harder for the ecosystem to adjust.

And we're already seeing some changes in plant life today, Overpeck said. The warming of the planet is creating dryer ecosystems in certain parts of the world, like the western U.S., Australia and Eurasia. "So what we're seeing in the western [U.S.] are whole regions of increased tree death because of warming and drying," he said.

"We are also seeing a big uptick in insect and disease in forests because these trees are being weakened by the warming," he added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.