Gallery: Secrets of Mount St. Helens

Secrets of the mountain

Mount St. Helens in Washington state sits about 40 miles (64 kilometers) west of other young volcanoes in the region, like Mount Adams and Mount Rainier. Now, researchers have found that the scars of ancient crustal collisions explain the volcano's position.

Electrical rocks

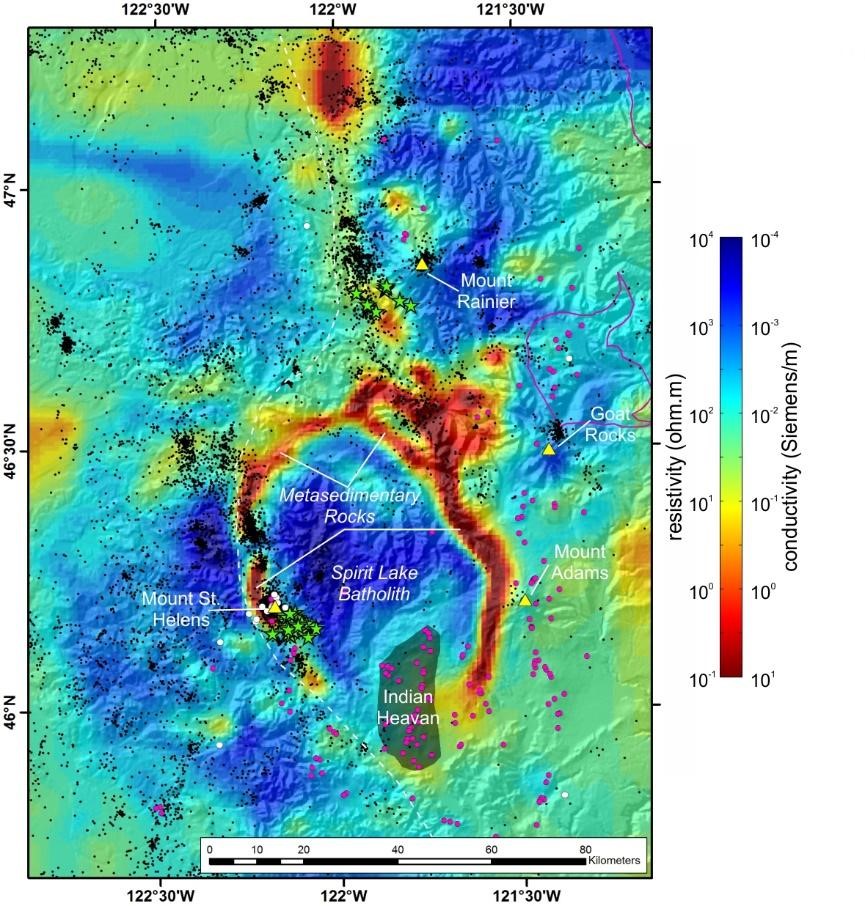

Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey, Oregon State University and the University of Canterbury used a method called magnetotellurics to measure the electrical conductivity of rocks deep below the Earth's surface. In two field seasons, the researchers deployed about 150 sensors around Mount St. Helens, Mount Adams and Mount Rainier to make the measurements.

Cascades Mountain Range

A map of the Cascades range through Oregon, Washington and California shows how Mount St. Helens is offset from the rest of the volcanoes in the chain.

Exploring rock formations

Goat Rocks Ridge in the Cascades of southern Washington, where researchers deployed instruments to measure the electrical conductivity of the crust. Different rock types have different conductivity, allowing researchers to reconstruct a map of the rocks underpinning these mountains and ridges.

Fieldwork

Oregon State University doctoral student Esteban Bowles-Martinez conducts fieldwork near Mount St. Helens. The project was part of a larger collaborating geared toward understanding the magma "plumbing" below the volcano.

Placing tools

Researchers deploy magnetotellurics instruments in the southern Cascades to measure the electrical conductivity of the crust. They discovered that Mount St. Helens sits west to a large chunk of cooled igneous, or volcanic, rock called a batholith that suppresses magma that might otherwise rise to the surface.

Past and current ground

While the area to the west of Mount St. Helens is relatively free of young volcanic vents, the mountain itself sits on a piece of former seafloor that was subducted under the North American continent by tectonic forces. This rock allows magma to rise to the surface.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hidden beneath

A map of the Earth's crust under Mount St. Helens and its surroundings. The seafloor rocks under Mount St. Helens were transformed under pressure when tectonic plates collided 40 million to 50 million years ago. The cooled igneous Spirit Lake Batholith is at least 20 million years old.

Study of the deep

The magnetotellurics method of studying deep rocks of the crust could be useful in other areas of unusual volcanism, said study co-author Paul Bedrosian, a geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey.

Result of eruption

A view of Mount St. Helens in 2008, after a period of mild eruptive activity that built a new lava dome on the mountain. Mount St. Helens erupted explosively in 1980, killing 57 people.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.