Here's How to Make the Sahara Desert Green Again

The Sahara is the world's largest hot desert, but parts of it could be made green if massive solar and wind farms set up shop there, a new study finds.

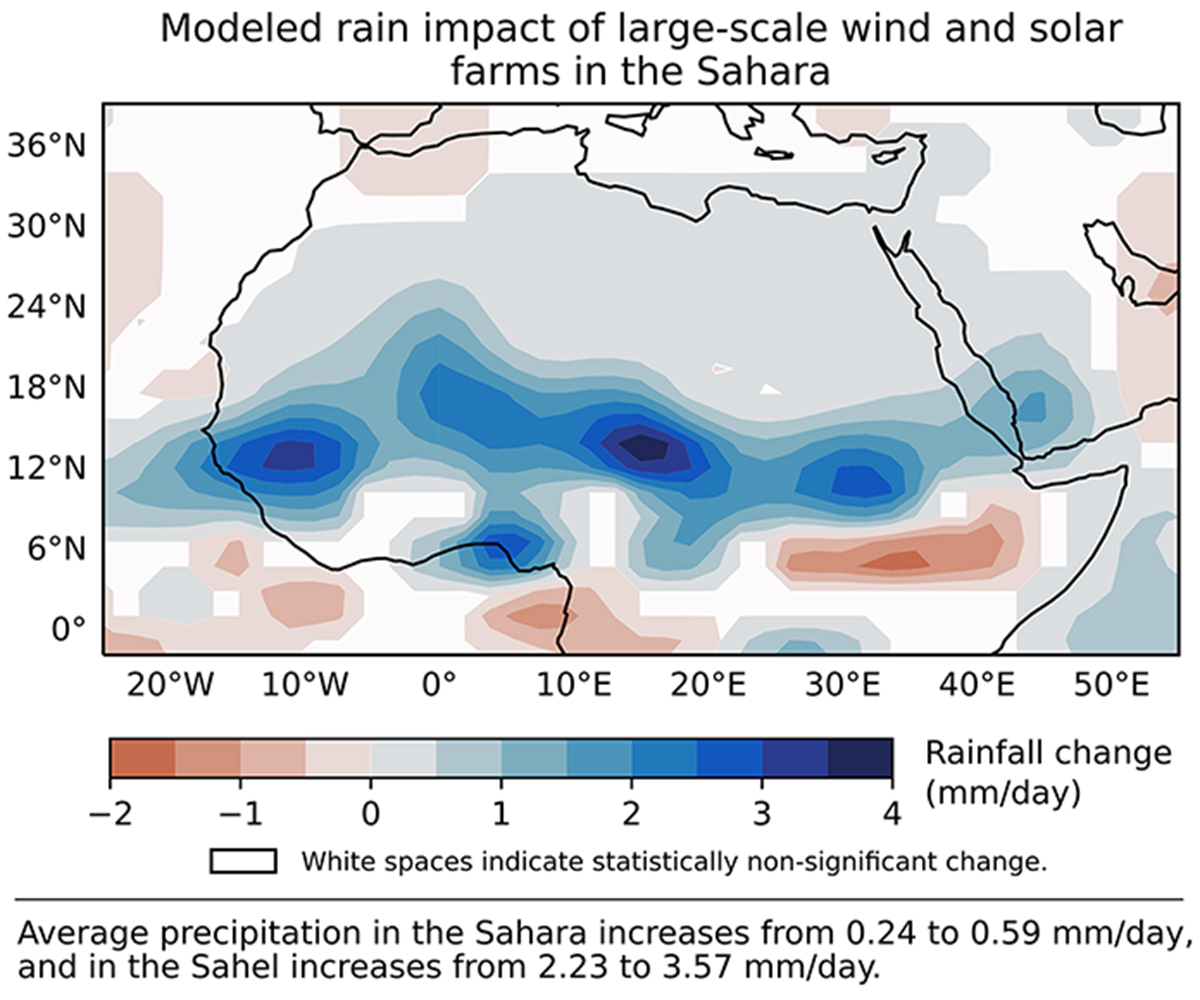

These farms could increase rain in the Sahara, especially in the neighboring Sahel region, a semiarid area that lies south of the giant desert, the researchers said in the study, which was published online Sept. 7 in the journal Science.

"This increase in precipitation, in turn, leads to an increase in vegetation cover, creating a positive feedback loop," study co-lead researcher Yan Li, a postdoctoral researcher in natural resources and environmental sciences at the University of Illinois, said in a statement.

Researchers already knew that wind and solar farms can increase the heat and humidity in the areas immediately around them. But this study is among the first to model how wind and solar farms would affect the Sahara, all while considering how growing green plants and trees would respond to these changes, said Li, who started the study while a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science at the University of Maryland. [The 10 Biggest Deserts on Earth]

"Previous modeling studies have shown that large-scale wind and solar farms can produce significant climate change at continental scales," Li said. "But the lack of vegetation feedbacks could make the modeled climate impacts very different from their actual behavior."

Li and his colleagues simulated what would happen if wind and solar farms covered more than 3.4 million square miles (9 million square kilometers) of the Sahara. On average, the wind farms would generate about 3 terawatts, while the solar farms would generate 79 terawatts of electrical power in one year, they found.

That's a lot of energy. One terawatt can power about 10 billion 100-watt light bulbs simultaneously. "In 2017, the global energy demand was only 18 terawatts, so this is obviously much more energy than is currently needed worldwide,” Li said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The model also showed that wind farms caused localized air temperatures to warm.

"Greater nighttime warming takes place because wind turbines can enhance the vertical mixing and bring down warmer air from above," the researchers wrote in the study. Rain also increased as much as 0.01 inches (0.25 millimeters) per day, on average, in areas with wind farms, the researchers found.

"This was a doubling of precipitation over that seen in the control experiments," Li said.

The Sahel would see even more rain; an increase of 0.04 inches (1.12 mm) a day in areas with wind farms, which would help vegetation there grow, the researchers said. That translates to an increase of between 8 and 20 inches (200 and 500 mm) of rain a year in the Sahel, enough that it would not be classified as a desert. (Deserts, by definition, are areas that receive less than 10 inches (250 mm) of annual rainfall.)

The solar farms would also have a positive effect on temperature and rainfall, the researchers noted.

"We found that the large-scale installation of solar and wind farms can bring more rainfall and promote vegetation growth in these regions," study co-lead researcher Eugenia Kalnay, a distinguished professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science at the University of Maryland, said in the statement. "The rainfall increase is a consequence of complex land-atmosphere interactions that occur because solar panels and wind turbines create rougher and darker land surfaces."

If this model ever becomes a reality, "the increase in rainfall and vegetation, combined with clean electricity as a result of solar and wind energy, could help agriculture, economic development and social well-being in the Sahara, Sahel, Middle East and other nearby regions," Safa Motesharrei, a systems scientist at the University of Maryland, said in the statement.

"The Sahara has been expanding for some decades, and solar and wind farms might help stop the expansion of this arid region," Russ Dickerson, a leader on air quality research and a professor at the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science at the University of Maryland who was not involved in the study, said in a statement. "This looks like a win-win to me."

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.