Scientists Just Found the Guys Who Are Killing Africa’s Elephants

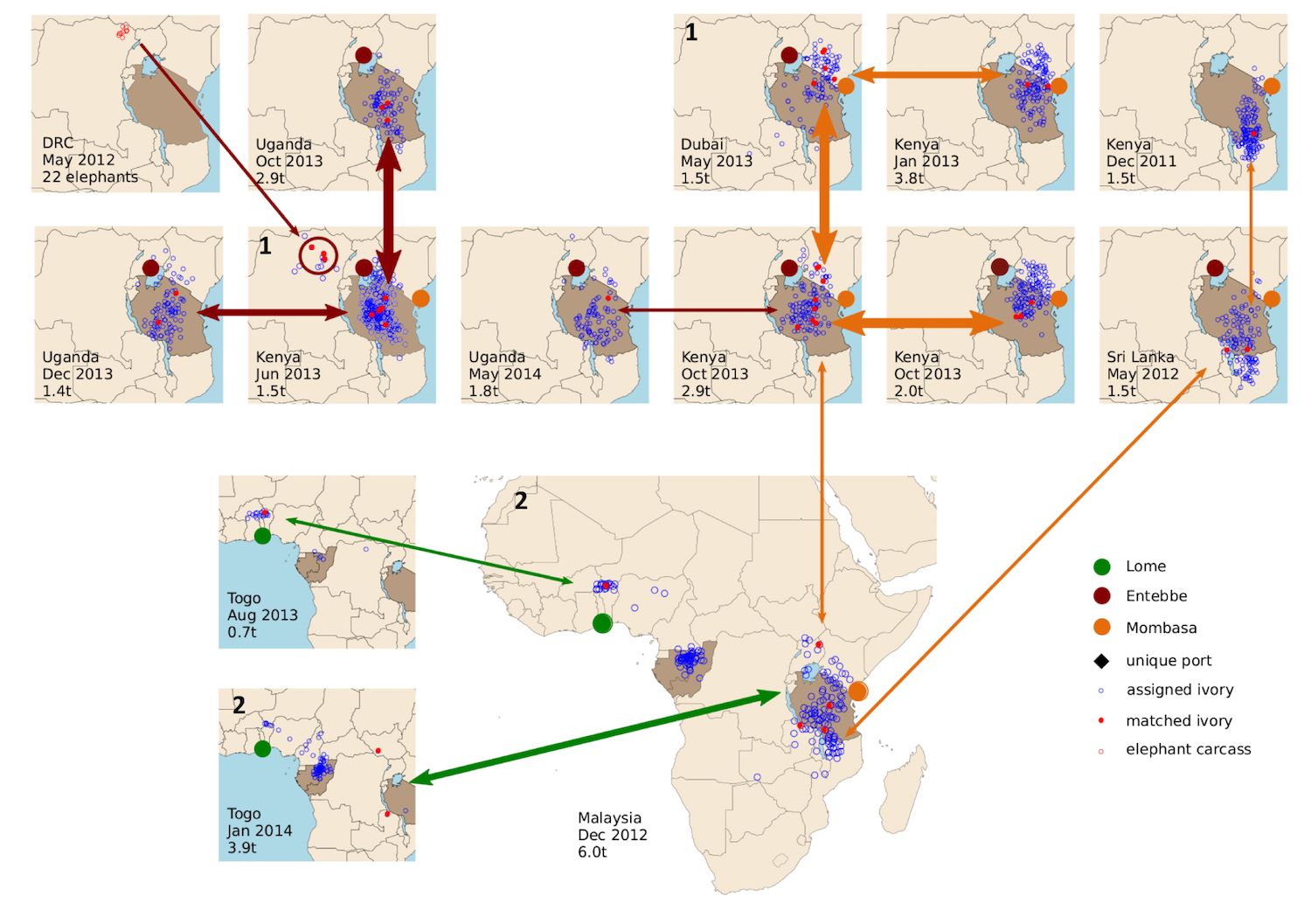

These geneticists have uncovered Africa's three largest ivory cartels — located in Mombasa, Kenya; Entebbe, Uganda; and Lomé, Togo — by analyzing the DNA within elephant tusks found in illegal trafficking shipments.

The findings reveal that cartels frequently put the right and left tusks from the same elephant in different shipments. By linking these tusks, scientists have discovered that these cartels sometimes work together, and the finding reveals the interconnectedness of Africa's largest ivory-smuggling cartels, the researchers reported in a new study. [Photos: Seized Elephant Ivory Reveals How Multimillion-Dollar Cartels Operate]

Moreover, by attributing smuggled tusks to specific cartels, scientists can help prosecutors strengthen their cases against ivory kingpins, said study lead researcher Samuel Wasser, director of the Center for Conservation Biology and a professor of biology at the University of Washington, in Seattle.

Chasing cartels

The fight against ivory cartels is not new. The international trade of elephant ivory has been illegal since 1989, but elephants are still killed in record numbers. Between 2005 and 2015, poachers killed as many as 111,000 elephants, leaving as few as 415,000 elephants in Africa, according to a 2016 report from the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

These days, ivory smuggling is a $4 billion industry, driven in part by the growth of the shipping-container industry, Wasser said. Ports can inspect only about 2 percent of the almost 1 billion containers that are shipped annually around the world, he said. "And traffickers merely now just containerize their contraband and get it into transit, and its shipment becomes virtually assured," Wasser said at a news conference yesterday (Sept. 18).

In a study published in 2015 in the journal Science, Wasser and his colleagues pinpointed Africa's two major poaching hotspots. The researchers did this by matching the DNA from smuggled tusks with DNA found in elephant poop, tissue and hair that they had previously collected in the wild and mapped. But this discovery didn't help catch poachers, Wasser found.

"To our surprise, the poachers still remain very hard to stop," Wasser said. "What we have realized is that the poachers are difficult to find because they operate in these large areas that they know really well, and even when they're apprehended, they only have as much ivory as they can carry."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So, the researchers decided to go after the cartels, which likely pay the poachers to kill the elephants. (For instance, "it costs about $25 for a bullet to kill an elephant, and these poachers don't have a lot of money," so it makes sense that the cartels are funding them, Wasser said.)

Tusk breakthrough

It was then that the researchers had the "important breakthrough," realizing that more than half of the tusks in large ivory seizures were unpaired, meaning that the right and left tusks from the same elephant were in different shipments, Wasser said.

To learn more, the researchers sampled 38 large ivory seizures made around the world from 2006 to 2015, including bones from 10 elephants that were killed by poachers from a helicopter in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In all, the researchers matched 26 pairs of tusks in 11 of the shipments — an impressive number, given that they were testing an average of just one-third of the tusks from each seizure. [Saving Elephants: Ivory Crush in Central Park (Photos)]

Even though these right and left tusks were separated, they were still shipped out of the same port from 2011 to 2014, a time when ivory trafficking was at its peak, Wasser said. In addition, the separated tusks were almost always shipped within 10 months of each other, and the tusks in the matching shipments tended to come from the same elephant habitats, Wasser and his colleagues found.

By analyzing the geographic origins of the tusks, the researchers were able to determine where each cartel hunted elephants. The scientists also figured out how large each cartel was, based on how many genetically matched tusks were found in different shipments. They found that cartels often change the final point of destination for these shipping containers during the voyage, making the containers difficult to track.

All of this data helped identify the three major cartels, which are clearly operating across the entire African continent, Wasser said.

Ivory traffickers

There's substantial evidence that one of these cartels is tied to Feisal Mohamed Ali, one of the most notorious ivory traffickers in Africa, Wasser said. Research from Wasser's group helped convict Feisal two years ago, when Feisal received a 20-year sentence. But Feisal was recently acquitted on appeal because of irregularities that happened during his trial.

"Feisal was initially tried for only one seizure, and that really illustrates the power of connecting individual cartels to multiple seizures," Wasser said. "And our hope is that the data presented in this paper and discovered by others can help strengthen the case against this cartel."

Emile N'bouke, allegedly the largest ivory trafficker in West Africa, was also convicted because of work from Wasser's group. At the time of his trial, N'bouke argued that he wasn't a big trafficker, but now evidence shows that the he was linked to Feisal's network in East Africa, Wasser said.

There's yet another trafficker Wasser declined to name because of an ongoing investigation who appears to be linked to "a major international incident where helicopters from Uganda were flying over northeast Garamba [in the Democratic Republic of the Congo] and were allegedly responsible for shooting 22 elephants," according to DNA evidence from the tusks, Wasser said.

Cartels that smuggle ivory are often involved in killing wildlife rangers, moving drugs and laundering money, too, so it's essential that law enforcement stop them, Wasser added. In addition, these cartels use smart businesspeople, who create rumors that elephant ivory and parts of other animals — such as rhino horn and pangolin scales — can cure medical maladies, which bumps up the price and demand for the contraband. [Pangolin Photos: Scaly Mammals Threatened with Extinction]

In effect, the findings shows that "wildlife genetics needs to be better integrated in policy making and law enforcement strategy design," said Sergios-Orestis Kolokotronis, an assistant professor of epidemiology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in New York, who was not involved with the study.

Going forward

Many challenges remain. It costs $110 to analyze the DNA in each tusk. "So, you can imagine, if you've got 1,000 tusks and you do every single one, well, that's $100,000, and your budget is not going to last very long," Wasser said. What's more, it can be challenging to get countries to give scientists immediate access to recently seized contraband — which is key, because sometimes, evidence goes missing soon after it's collected, Wasser said.

The study is "excellent," said Al Roca, an associate professor in the Department of Animal Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who was not involved in the study. But he, too, noted the price. "It involves quite a bit of work and genotyping of many tusks, so one financial concern would be whether law enforcement agencies will continue to provide support for these efforts, which are critical," Roca told Live Science.

Roca noted that there are many steps that need to be taken to fight wildlife trafficking.

"Major ones include the political will of governments to stop smuggling, by fighting both the supply, as well as the demand, for wildlife products from some rather morally bankrupt consumers," Roca said. "The message of this study is that DNA-based methods can play a role in exposing smuggling operations and in determining the geographic regions and countries that are being targeted for poaching."

The study was published online today (Sept. 19) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.