How do flat-Earthers explain the equinox? We investigated.

Equinoxes would be physically impossible over a flat Earth, but that doesn't stop conspiracy theorists from trying to explain them.

The spring equinox is upon us. On Monday (March 20), the sun will shine directly on the Earth's equator, spring will officially begin in the northern hemisphere, and the length of day and night will be nearly equal across the globe ... or, "across the disk," if you're a flat-Earther.

For flat-earthers — the vocal online community of folks who believe the world is actually flat and science is a conspiracy — the equinox can be tricky to explain. Without axial tilt, the phenomenon in which the rotating, spherical Earth angles its poles toward or away from the sun, how can the changing seasons be reliably explained? How can sunrises and sunsets occur if the sun is constantly shining on the entire, flat surface of the planet? If the North Pole sits at the exact center of the world, can compass directions even exist?

Related: 7 ways to prove the Earth is round

Flat-Earth thinkers have come up with many answers to these niggling questions over the last century or so, and we've scoured the literature to share the explanations with you. Be warned: Understanding them requires discarding a few thousand years of what you might consider accepted scientific knowledge. For starters, forget the heliocentric model of the solar system. You won't need it here.

The sun is really, really small

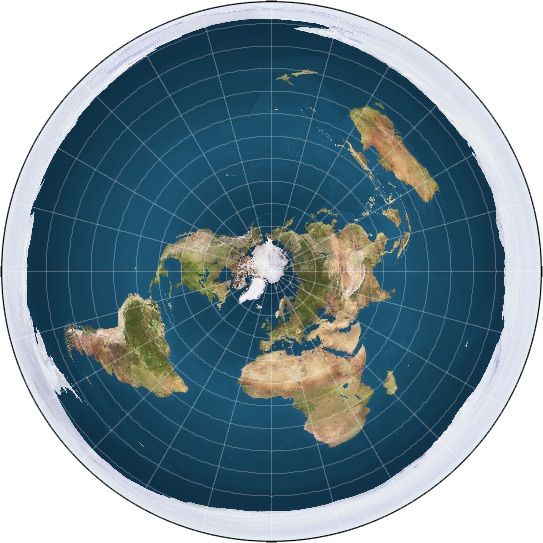

In the most popular flat-Earth maps, the North Pole sits roughly at the center of the planetary disc, while Antarctica forms a giant ice wall along the planet's circumference. The equator forms a ring hallway between the two.

Many flat-Earthers agree that the sun perfectly circles the ring of the equator on the equinox; however, to account for the equal hours of daytime and nighttime, the models make a few tweaks to how the sun itself looks and behaves.

While you might envision the sun as an enormous ball of exploding gas located 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) away, a flat-Earther would see it as a teeny, tiny spotlight hovering just over the Earth. How teeny and how close is it? According to the early flat-Earth thinker Samuel Birley Rowbotham, who published the influential treatise "Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe" in 1881, the sun is only about 32 miles (52 km) in diameter and hovers anywhere from 400 to 700 miles (640 to 1,130 km) above the Earth, depending on the month.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many modern flat-Earthers now believe that the sun sits about 3,000 miles (5,000 km) over the Earth, but Rowbotham's general idea remains popular in the community. Here's how members of the Flat Earth Society (one of the foremost flat-Earth activist groups in the world) describe the idea on their official wiki page:

"The sun moves in circles around the North Pole. When it is over your head, it's day. When it's not, it's night. The light of the sun is confinedto a limited area, and its light acts like a spotlight upon the Earth."

The diameter of these sun-circles governs the seasons. According to one popular theory, the sun circles closest to the North Pole in June, then spends the next six months spiraling slowly outward toward the ice wall at the edge of the world. In December, the sun reverses course and spirals back inward again.During the spring and autumn equinoxes, the sun circles in a perfect loop around the equator, casting light on half of the disc world at any given time. Voila: seasons!

Is that … possible?

This explanation has its problems. For starters, a sun circling 3,000 miles (5,000 km) above a flat Earth would never actually "set," even at the most southern latitudes. YouTube user Wolfie6020, a globe-Earth proponent, demonstrated this by building a scale model of the flat-Earth-style sun as it would be seen from Sydney on a vernal equinox. As shown in his video, the sun (actually a drone carrying a ping-pong ball) never dips below the horizon, even at its farthest point from the observer.

Moreover, during an equinox, the sun appears to rise due east and set due west everywhere on Earth except at the poles. For this to hold true on a flat Earth, where some cities are physically many times farther away from the sun than others, the sunlight would have to bend at hundreds of different angles simultaneously. That's the only way it could appear as if it was always coming from the east. YouTube user Flat Out, another prolific globe-Earth proponent, demonstrated the impossibility of this explanation using simple computer simulations in 2017.

So far, no flat-Earth model has been able to resolve these problems. But that doesn't stop the community from trying — or, in some cases, not trying. Like many conspiracy theories, it's the uncertainty that makes flat-Earth theory a mystery worth obsessing over for its proponents. So, whatever you believe, we hope this year's equinox restores your wonder in the globe/disk we call home.

Editor's note: This article, originally published in 2018, was updated on March 20, 2023.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.