Traces of an Ancient Virus in Our Genes May Play a Role in Addiction

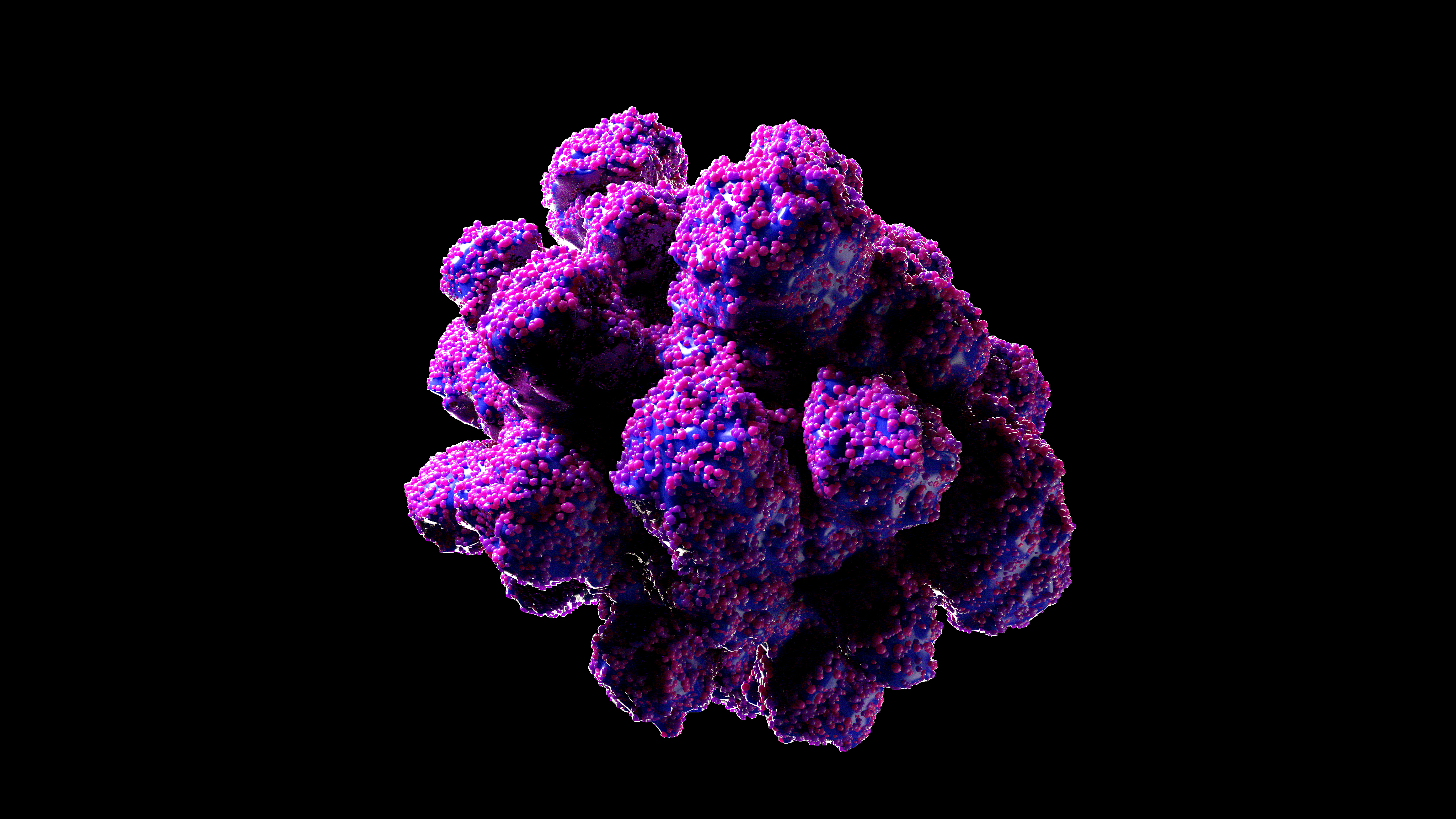

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, our ancestors were infected by a retrovirus. Now, some researchers think that that virus' ancient genetic traces still present in some people's genomes are silently promoting addictive behavior.

Genetic traces of a retrovirus called HK2 is more commonly found in people with drug addictions than those without addictions, and these traces may influence surrounding genes , which, in turn, might influence human behavior, an international group of researchers reported today (Sept. 24) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Retroviruses — which include HK2 as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — are viruses that can insert their genetic code into their hosts' DNA. It's thought that around 5 to 8 percent of the human genome is filled with traces of ancient retroviruses that found their way into our genes by infecting our ancestors eons ago. [America's Opioid-Use Epidemic: 5 Startling Facts]

For the most part, those ancient retrovirus signatures don't differ much between people — in other words, you and a random person you encounter likely carry the same kinds and amounts of these ancient traces in your genes. In contrast, traces of the HK2 virus are thought to exist in only 5 to 10 percent of people worldwide.

That means that, in the grand scheme of evolution, this viral infection occurred relatively recently, so it hasn't had time to even out among populations, or be chipped away at by natural selection. "Relatively recent," in this case, means that it's been lurking in human genes — and was also present in Neanderthal and Denisovan genes — for at least 250,000 years.

Lurking ancient infections

In the first part of the new study, two groups of researchers, one from the University of Athens in Greece and the other from the University of Oxford in the U.K., analyzed people's DNA to see if those who had traces of HK2 in their genes were more likely to have addictive tendencies.

In Greece, researchers analyzed the genes of more than 200 people who had HIV, and in the U.K., researchers analyzed DNA from about 180 people with the hepatitis C virus. Both viruses can be spread through intravenous drug use.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team in Greece found that those who contracted HIV from intravenous drug use were 2.5 times more likely to have traces of HK2 in their genome than those who became infected through other means, such as sex. Similarly, in the U.K., those who contracted hepatitis C through intravenous drug use and were long-time drug users were 3.6 times more likely to have HK2 in their genes than those who weren't infected through drug use.

It was previously known that, in people with traces of HK2 in their DNA, those traces can be found in a gene called RASGRF2, which plays a role in the release of dopamine in the brain. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that's tightly entwined with the brain's pleasure circuit, and is thought to promote the repetition of pleasurable activities. What's more, the chemical can change the way the brain is wired to get someone to repeat pleasurable activities, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug use is known to release large surges of dopamine in the brain.

In the second part of the study, the researchers investigated whether HK2 traces had any influence on human genes. In a lab experiment, the scientists used genetic "scissors" — CRISPR-Cas9 — to insert traces of HK2 into the DNA of human cells that didn't already contain it. Specifically, they inserted the viral traces into the exact location where it's been found in human DNA, in the RASGRF2 gene.

They found that inserting traces of the ancient virus changed the expression pattern of RASGRF2; in other words, it changed the process by which information stored in DNA was used to create proteins.

Still, as this second experiment was done in lab dishes, not in humans, the impact this finding has on addictive behaviors remains unclear.

Could targeting ancient viruses lead to better interventions?

The new study is "the first time that [researchers have] shown that an ancient viral insertion that's variably present in the population has a measurable, in this case detrimental, effect on our biology," said co-senior study author Aris Katzourakis, a professor of evolution and genomics at the University of Oxford who led the U.K. portion of the study. Katzourakis added that the first part of the study — in which the researchers observed higher rates of the viral traces in drug users — only shows an association, but the second part of experiment shows the viral insertions causing changes in the biology of the cells.

What's more, the "integration of the virus happened thousands of years ago, [which] predates the addictive behaviors that we see today," Katsourakis told Live Science. In their paper, the researchers suggested that perhaps, at one point, the integration of this virus was beneficial for humans, and that's why it prevailed for some time, escaping the grasp of natural selection.

Now, the teams hope to understand exactly how the HK2 traces may influence addictive behaviors. This could potentially lead to "better intervention strategies," Katsourakis said. "If we can make a drug to target this insertion, we may be in a better place to help people recovering from this kind of behavior."

"I think the implications of this research [are] huge," said Andrew Xiao, an associate professor of genetics at Yale University's Stem Cell Center who was not part of the study. "It tells us there are a lot of vulnerable spots [in the genome] that will be subject to viral integration." People have suspected this, and have gathered data on it for a long time, but "I think the relevance to human disease is pretty fresh," he told Live Science.

Still, much more research is needed. "I think it’s a very good start for a lot of interesting work lay ahead," Xiao added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.