This Was the World's Largest Bird. It Weighed As Much As a Dinosaur.

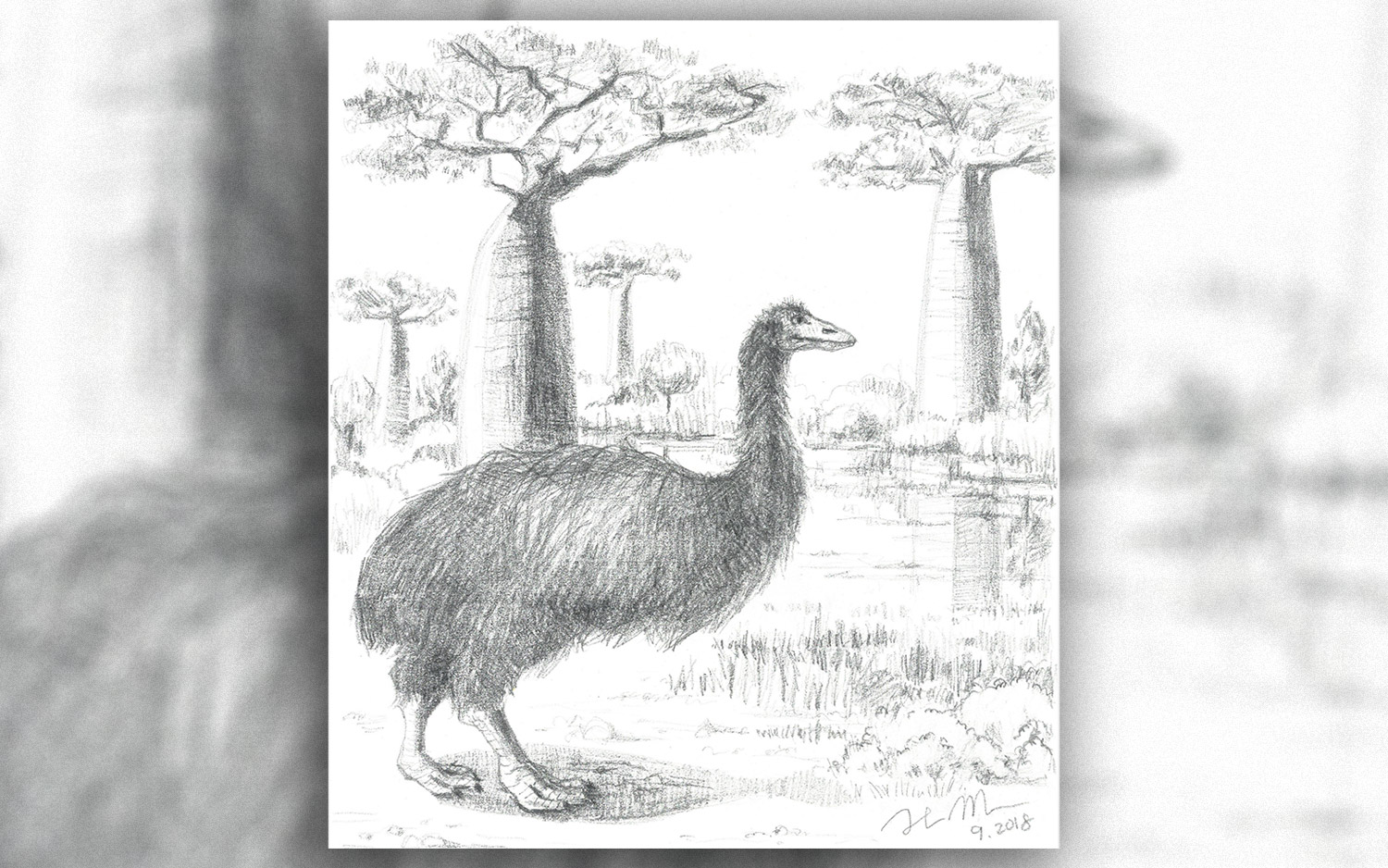

The world's largest bird — a newly identified species of elephant bird — weighed as much as a dinosaur when it strutted around Madagascar more than 1,000 years ago, a new study finds.

This monster bird is now extinct, but it weighed as much as 1,760 lbs. (800 kilograms), or about as much as seven modern-day ostriches when it was alive. It also stood a whopping as 9.8 feet (3 meters) high — a good 8 inches (20 centimeters) taller than an ostrich.

And, also like the ostrich, this elephant bird couldn't fly. [15 of the Largest Animals of Their Kind on Earth]

Researchers have actually collected the bones of elephant birds (Aepyornithidae) since the mid-1800s, but they misattributed the newfound giant to another species of elephant bird, known as Aepyornis maximus, said study lead researcher James Hansford, a postdoctoral researcher at the Zoological Society of London's Institute of Zoology.

"Understanding the diversity in these extinct giant birds has been a taxonomic knot for some 150 years," Hansford told Live Science. Paleontologists were so gung-ho about the discovery of elephant birds in the 1800s and early 1900s, they began naming species left and right, often from incomplete specimens.

To set the record straight, Hansford used a tape measure and calipers to analyze hundreds of elephant bird bones that were housed at museums around the globe. Some of these bones were broken, so he devised a computer program to fill in the gaps.

After plotting the bones' sizes in a computer program, Hansford found that these bones fell into distinct clusters, revealing three genuses (also known as genera) and four distinct species. He named the newfound fowl Vorombe titan, whose genus name means "big bird" in Malagasy. Its species name, "titan" is a throwback to Aepyornis titan, which a British paleontologist named C.W. Andrews had mistakenly used to dub the bird. Later, it was (again) erroneously classified as another elephant bird species, A. maximus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As a funny side note, Andrews was friends with the English writer H.G. Wells, who wrote a short story joking that after naming these big birds Aepyornis maximus and Aepyornis titan, "if they get any more [even larger] Aepyornises … some scientific swell will go and burst a blood vessel."

Luckily, no blood vessels were burst when Hansford found V. titan, which is even larger than A. maximus, previously thought to be the largest bird in the world. (In the past, some scientists argued that the moa, another extinct flightless bird once found in what is now New Zealand, was the biggest bird on record. Now, with the discovery of V. titan, the record-holder is clear, Hansford said.)

V. titan is so big, that its average weight of 1,430 lbs. (650 kg) is comparable to Europasaurus, a small sauropod (a long-necked dinosaur), which weighed about 1,500 lbs. (690 kg), Hansford and study co-researcher Samuel Turvey, a professor at the Zoological Society of London's Institute of Zoology, wrote in the study.

When the herbivorous elephant birds went extinct about 1,000 years ago — largely because of human hunters — the Madagascar ecosystem changed. Plants that depended on the birds to eat and disperse seeds faced a daunting battle for survival.

Elephant birds "undoubtedly had a significant impact on creating and maintaining the landscape in ancient Madagascar," Hansford said. "And their extinction has left a hole that we need to think about conserving in their absence." [In Images: Wacky Animals That Lived on Mauritius]

In effect, "we're using the past to inform conservation plans," Hansford said.

The new finding "probably cements the case for this being the largest bird," said Daniel Ksepka, a fossil bird expert and curator at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, who was not involved in the research.

Ksepka noted that even though DNA degrades rapidly in warm places such as Madagascar, it would be interesting if researchers are ever able to extract DNA from elephant bird bones. That's because the female moa is almost twice the size of the male moa, so it's possible that some of these bird specimens are merely males and females of the same species. However, the researchers wrote that this is unlikely, as there are "complex patterns of variation" between the different bone clusters.

The study was published online today (Sept. 26) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.