'Thunderclap at Dawn' Dino's Totally Metal Name Honors Colossal Size

If any rock bands are looking for a cool name, they might draw inspiration from a newly identified long-necked Jurassic giant whose moniker means "a giant thunderclap at dawn."

This colossal dinosaur was the largest beast alive during the Early Jurassic. And it walked in a peculiar way, a new study finds.

Unlike the later long-necked dinosaurs and even today's elephants, the "giant thunderclap" dinosaur didn't walk on straight limbs. Rather, the 13-ton (12 metric tons) dinosaur moved with "a more crouched posture," study senior researcher Jonah Choiniere, a reader in dinosaur paleontology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, told Live Science. [Titanosaur Photos: Meet the Largest Dinosaur on Record]

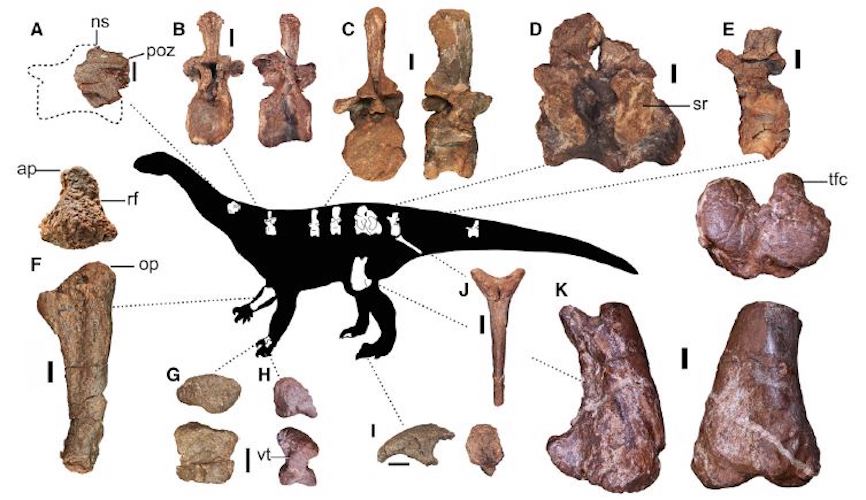

Researchers initially unearthed fossils of the 200-million-year-old dinosaur in the late 1980s near South Africa's international border with Lesotho. But it took them until 2017 to excavate all the beast's remains, including a wristbone that helped the team determine how the dinosaur walked.

They drew from Southern Sotho, a Bantu language spoken in the region, to dub the dinosaur Ledumahadi mafube, which (as mentioned) is a nod to the beast's giant size. The genus name (Ledumahadi) means "a giant thunderclap" in recognition that size, whereas the species name (mafube) means "dawn," as a reference to the animal's existence during the Early Jurassic.

"Nothing larger than Ledumahadi had ever walked the Earth when it evolved in the earliest Jurassic," Choiniere said.

At 49 feet (15 meters) long, L. mafube would have been quite a sight. The enormous plant-eater stood about 13 feet (4 m) tall at its back hips and a little lower in front. It had a skinny neck, a tiny head and a long tail.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

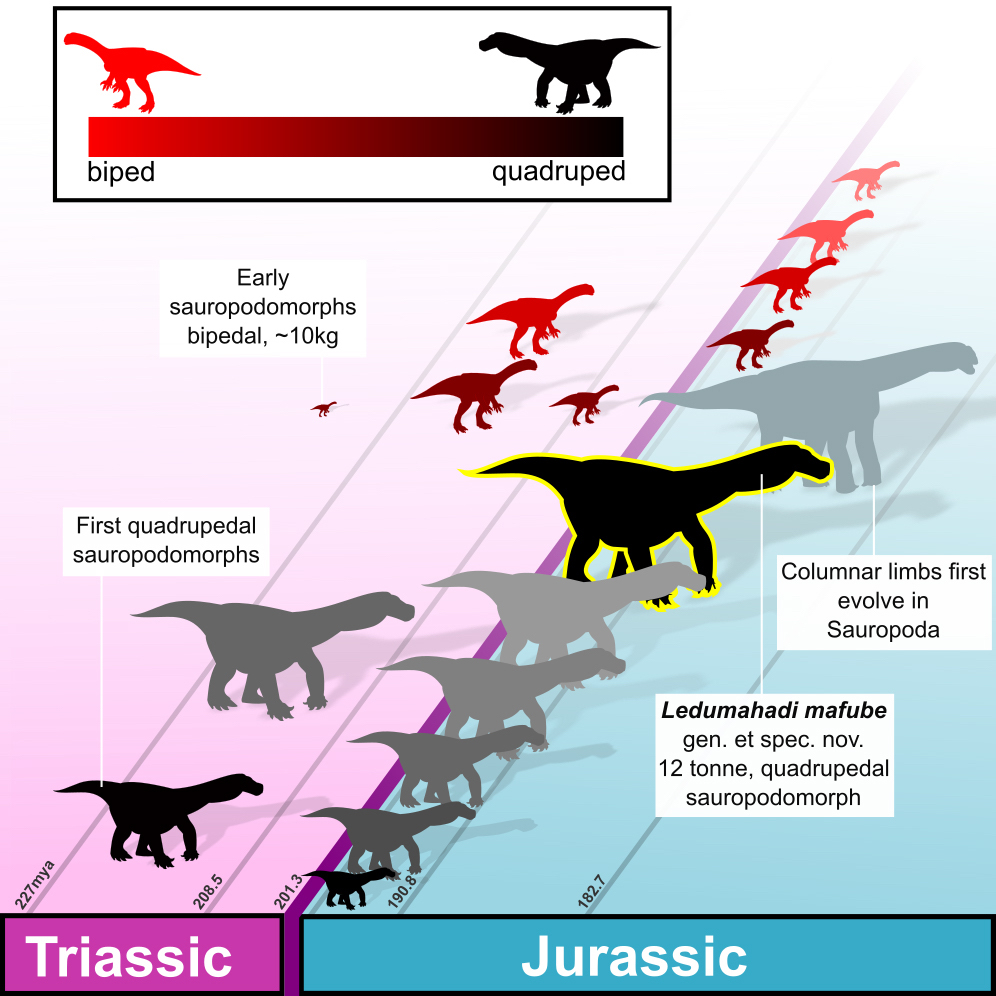

Despite its long neck and tail, the "giant thunderclap" wasn't a sauropod dinosaur like the famous Brontosaurus, but a sauropodomorph, one of the closest relatives of the sauropods. Surprisingly, "Ledumahadi was bigger than some true sauropods, and its early [Jurassic] age means that gigantic body size appeared early," Choiniere said.

In other words, L. mafube evolved its giant size independently of the sauropods, Choiniere said.

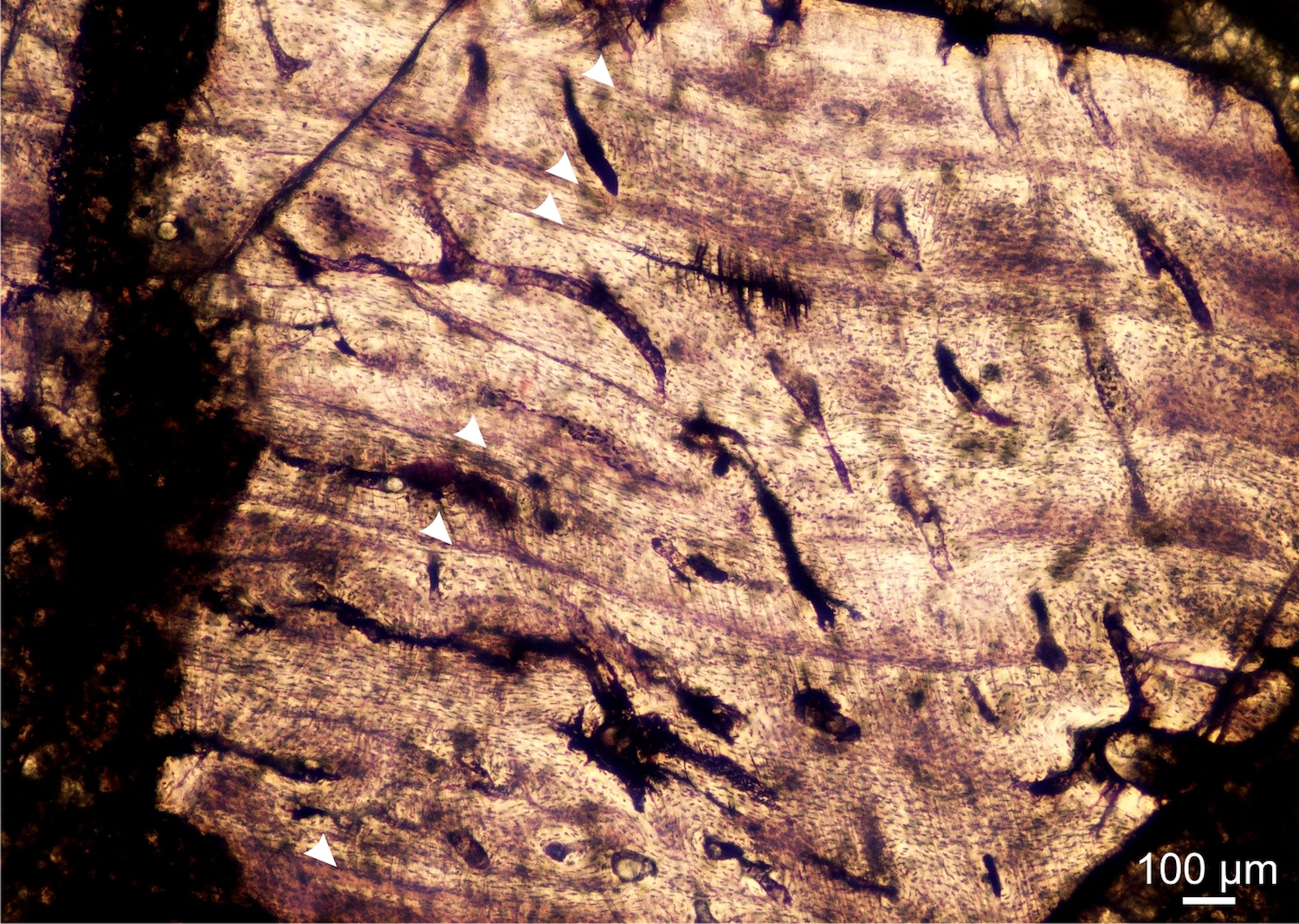

An analysis of the growth rings within the fossilized bones (dinosaur bones laid down rings as they grew, much like trees) revealed that when the dinosaur died, at 14 years of age, "thunderclap at dawn" was a fully grown adult. A further investigation of the dinosaur's upper arms and thighs showed that the beast walked on four legs, instead of two like some earlier and smaller sauropodomorph dinosaurs.

"It walked on all fours, but unlike an elephant, which has very rigid, erect legs, its stance would have been more crouched, like a cat or a dog," Choiniere said.

However, L. mafube isn't the first known sauropodomorph to walk on all fours. That honor goes to Riojasaurus, a sauropodomorph dinosaur that lived in what is now Argentina about 220 million years ago, during the Triassic period. [Gallery: Massive New Dinosaur Discovered in Sub-Saharan Africa]

"We don't know yet why quadrupedalism evolves, but we do know that it evolves independently, multiple times in Sauropodomorpha and in Ornithischian [bird-hipped] dinosaurs, both of which eat plants," Choiniere said. "There is some thought that the huge reservoir of a gut system that held plant matter in these [groups] might have shifted the center of gravity forward for the animal, so that having an additional support in the forelimb would have been advantageous."

The finding shows that some sauropodomorph dinosaurs reached huge sizes and that they achieved this with "different anatomical solutions," — that is, by using flexed limb postures, said Patrick O'Connor, a professor of anatomy at Ohio University, who was not involved with the study.

Later, giant sauropods carried their weight on legs with an "upright, columnar limb organization — quite different from that inferred for Ledumahadi," O'Connor told Live Science in an email.

The study was published online today (Sept. 27) in the journal Current Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.