A Physicist Said Women's Brains Make Them Worse at Physics — Experts Say That's 'Laughable'

A male physicist claimed during a lecture that men are discriminated against in physics. He also said that there are fewer women than men in physics largely because of innate differences in intelligence between the sexes, and partly because women are less interested in physics.

But experts in neuroscience, intelligence and the interactions of gender and society told Live Science that they weren't impressed.

"I find that pretty laughable, actually," said Maria Natasha Rajah, a cognitive scientist and expert in neuroimaging at McGill University in Quebec.

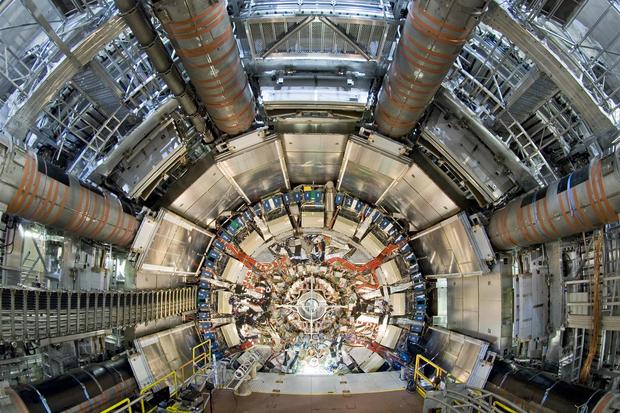

Alessandro Strumia, the physicist in question and a professor at Pisa University in Italy, gave his presentation to a crowd at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), one of the word's most important nuclear physics organizations. The topic of the day was gender in physics, and the crowd was mostly composed of women, according to The Guardian.

Over the course of several slides of his presentation, which are available online, Strumia laid out an IQ-based argument for disparities between men and women in physics.

"Physics graduates have top IQ," he wrote. "It's needed."

He pointed to a study that suggests that while men and women have similar average IQs, men vary more, with very slightly more men at the low and high ends of the spectrum. This is the truth behind gender differences in physics, he argued. And efforts to bring gender balance to physics are the result of "cultural Marxism" and politicians "promoting a victimocracy" and "ideology" ignoring "blind human biology," he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

He further argued that men are discriminated against in physics, presenting data suggesting that men at CERN have more total citations, on average, than women. (The raw number of times one's papers have been cited is sometimes considered a mark of prestige in academia.) He also argued that a single example where a woman with fewer citations than him was hired over him was evidence of this bias. (In fact, a woman, Donna Strickland, was awarded part of the Nobel Prize in physics this morning (Oct. 2), for the first time in 55 years.) [7 Women Who Broke Barriers in Science and Tech]

Live Science spoke to experts in cognition, IQ and the sort of data-driven gender disparity research Strumia attempted to conduct here. Here's what they had to say.

On men's and women's brains

"There are some studies that show differences in brain structures," between men and women, Rajah said. "Sometimes, it's women that have larger areas of the brain and sometimes it's men, depending on what you're talking about."

The main reason for that, she said, is likely hormonal differences during development, which are thought to have some impact on brain development. [10 Surprising Facts About a Man's Brain]

But it's a huge leap to say those brain differences make men better physicists, she said, because for the most part scientists don't know how these slight brain differences impact cognition — or which sex, if either, is better off because of those differences. Further, and more important, on a biological level, men and women overlap vastly more than they diverge.

Evidence suggests, she said, that society and life experience play much larger roles in distinguishing the sexes than brain differences.

"You're learning from day one and you're in society from day one," she said. "We know that children by the time they are 4 or 5 [years] of age, they are already using gendered language and attributing words like 'intelligence' or 'brilliance' more to men."

Any judgment about men's and women's mental abilities from experiments following years of societal interference is inherently flawed, she said.

What we do and don't know about IQ

You've probably heard about IQ — a test that's supposed to measure innate intelligence. But many neuroscientists don't take IQ tests very seriously as measurements of essential intelligence, because these tests are easily confounded by cultural differences and years of education, Rajah said. [Are Big Brains Smarter?]

That said, there are researchers who look at IQ, other measures of intelligence and the factors that influence them. One of the most well-known is Stuart Ritchie, a psychologist at the University of Edinburgh. He and his colleague published a study in June in the journal Psychological Science showing that education is the single strongest factor known to raise IQ scores.

"The claim about males and females having the same [average] IQ but males having a wider variance is true," Ritchie told Live Science. "This is what's found in almost every study."

There is a sensible discussion scientists could have about that, Ritchie said, But it isn't enough to justify Strumia's claim, he said.

"The question is," he said, "is a wider IQ variance … of the size found in these studies, enough to explain the wide disparity in high-IQ STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] professions like physics?"

Strumia did appear to do a bit of math based on limited data to suggest that this is the case, but Ritchie pointed to a study of 1.6 million students published online Sept. 25 in the journal Nature Communications suggesting something else is going on. Researchers found that girls performed better overall than boys on academic tests in STEM and non-STEM subjects, with boys exhibiting more variance. (In other words, women were better at STEM tests, but there were more boys at the top and bottom of the score charts.) However, the researchers also found that this variance is more significant in non-STEM fields than in STEM fields, which should mean that you'd see more women in STEM professions. [6 Myths About Girls and Science]

"[This] is not what you'd expect if the disparity was what was driving the STEM disparity," he said. "So, there must be more than pure ability going on. This is where sexism or the so-called 'leaky pipeline' might play a role."

The 'leaky pipeline'

The "leaky pipeline" is a phrase sometimes used by researchers to describe the factors that keep women from becoming career researchers, while men in their cohort are pushed forward.

A range of problems — including teachers and parents who push more boys than girls toward STEM, a lack of visible women scientists in the lives of girls, as well as systemic discrimination and hostile work environments in science — have been proposed as contributing factors, with research supporting all of those claims. (There's evidence demonstrating that these factors are more extreme for non-white women.)

Regardless of what factors precisely are most important in producing gender gaps in science, said Philip Cohen, a sociologist and expert in the data on societal inequality at the University of Maryland, it's clear women are driven out of STEM early on.

"The mechanism for that imbalance in math and physics shows up early in life, during that transition into high school, when girls stop [on average] being better than the boys in math and science," Cohen told Live Science, citing data from a book published in 2013 by sociologists Thomas DiPrete and Claudia Buchmann.

"It appears that whatever is happening in their education is not propelling or encouraging them to follow up on their interests in math and science," he said.

Further, he said, it would be silly to assume from the available data that women and men start off on equal footing in these careers.

"It was just a couple generations ago that these fields were all-male by rule," Cohen said.

And to this day there's evidence that STEM fields remain hostile to women, Cohen added — pointing out the reality that, at least in physics, men like Strumia still feel comfortable giving talks suggesting women don't belong.

"So, it would be quite a coincidence [if something else were causing the disparity]. It's just too convenient to look at the system that that legacy produced and write it off to biology," he said.

As for the differences in citations among men and women at CERN, that's just a poor use of data, Cohen said.

"He [Strumia] probably should have consulted a social scientist," Cohen said.

In addition, citations are a better measure of how much time a person has spent exclusively focused on publishing paper after paper, Cohen said — not necessarily how good their research skills are. And there's lots of research showing that STEM fields and society are structured to make it more possible for men to do this than women.

"You often see the drop-out of women from STEM at very critical stages that have to do with quality of life changing," Rajah said. "So, getting married, having children. And that's why you often see attrition around postdoc [a job often taken after acquiring a doctorate, but before becoming a professor], so around [age] 28, 32."

Later in academics' careers, Rajah said, there's another period where women tend to disappear from research.

"You just have to look at hiring committees and the structure of the academic universe to see that there is less female representation [in positions of power] the higher up you go, so for this guy to say that men are the ones who are being penalized is really pretty laughable."

Originally published on Live Science.