Stone Engravings of Famous Warrior Pharaoh Found in Ancient Egyptian Temple

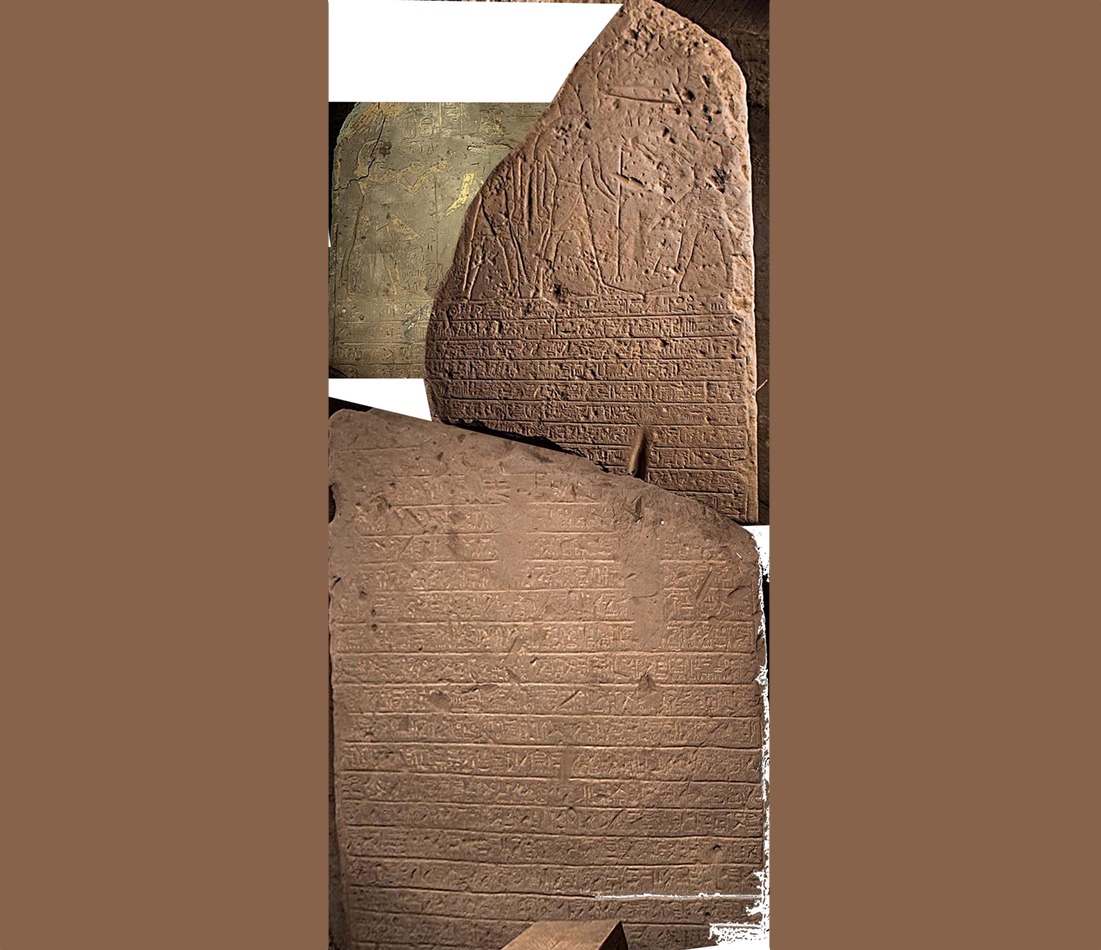

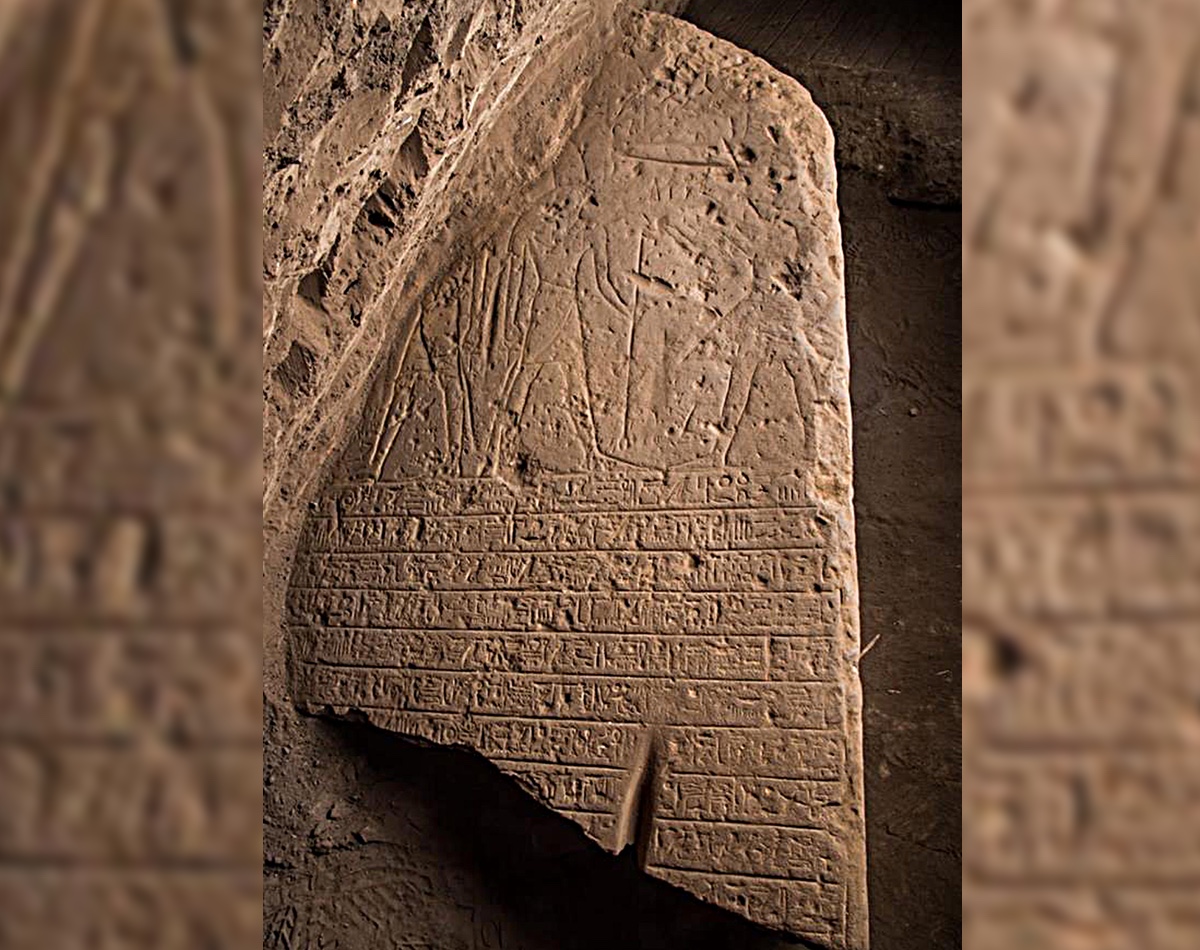

A giant stone engraving that fits together like a jigsaw puzzle, found in a temple in southern Egypt, may reveal new information about a pharaoh named Seti I, who launched a series of military campaigns in North Africa and the Middle East after he became pharaoh in about 1289 or 1288 B.C., several Egyptologists told Live Science.

The engraving has both drawings and hieroglyphs on it; the engraving mentions an event that happened during the reign of Horemheb, an elite general in King Tut's army who eventually became a pharaoh.

Archaeologists with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities discovered the engraving while conducting a groundwater-lowering project in Aswan; inside Kom Ombo, a temple dedicated to the god Horus and a crocodile-headed god named Sobek. The temple dates back 2,300 years; the engraving may have originally been in an earlier temple, now lost, at Kom Ombo that was located on the same spot as the later temple. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Live Science sent images released by the ministry on Sept. 30 to several Egyptologists who gave their perspectives on what the inscriptions say.

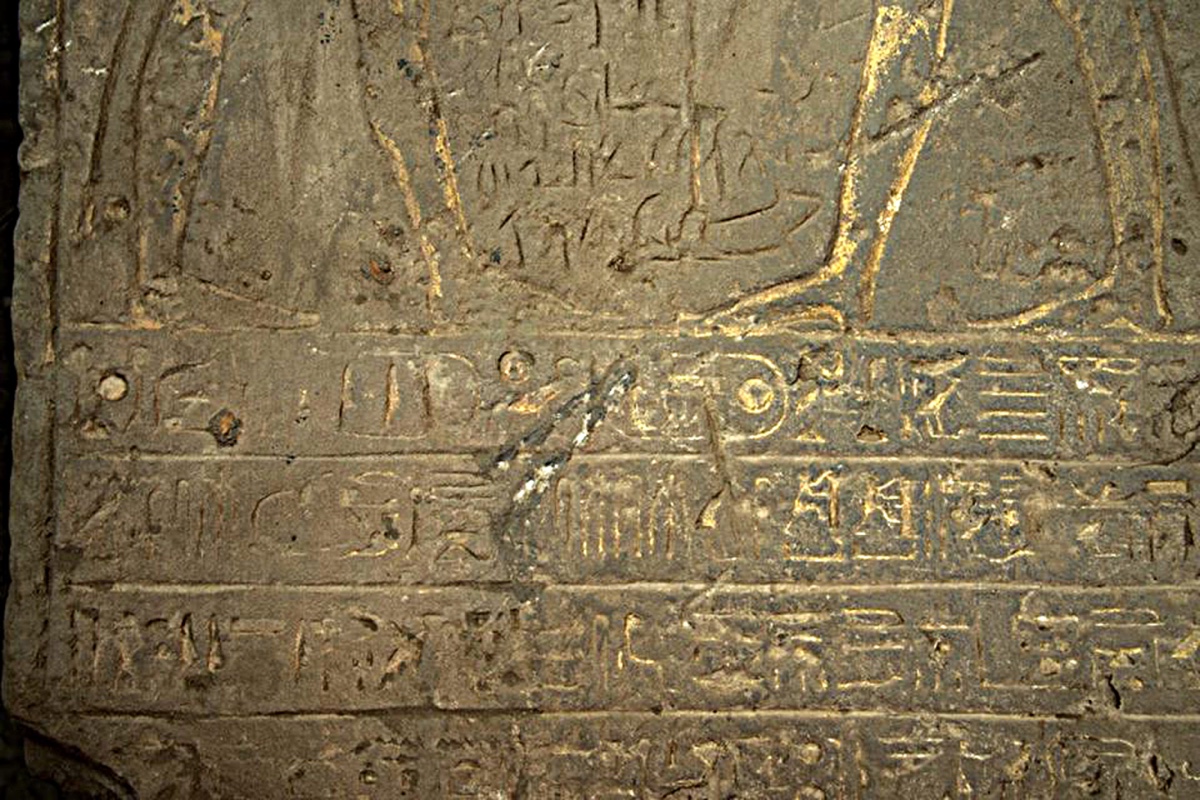

"This is an exciting discovery and may be historically important," said Peter Brand, a professor of ancient history at the University of Memphis in Tennessee. The engraving, which still has yellow paint on it despite the passage of 3,300 years of time, shows Seti I worshipping Sobek and Horus, said Brand, noting that it appears to date to early in Seti I's reign.

"This [inscription] proves that the double cult of these two gods [Horus and Sobek] was already established at Kom Ombo in the 19th Dynasty of the New Kingdom period, more than 1,000 years [before] the later temple was built," Brand told Live Science.

Brand can't tell from the photos precisely what the inscription says but "this was a major royal inscription and likely contains some kind of royal decree about the king's activities in the region, perhaps a dedication to the temple of Horus and Sobek [at] Kom Ombo," Brand said. Another inscription left by Seti I (also spelled Sety I) was discovered in the past at a site called Gebel es-Silsilah, which is located to the north of Kom Ombo. "Perhaps Sety was traveling through his realm in Year One [of his reign] and made stops at Gebel es-Silsilah and then at Kom Ombo on his way south from Thebes, modern Luxor," Brand said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It "would be wonderful if the text [of the inscription] contains a report on the king's military activity," Brand said, noting that Seti came from a family of military generals, and after he became pharaoh, he launched military campaigns to conquer Libya, Canaan, Syria and Nubia.

The inscription mentions Horemheb, who was pharaoh until around 1293 B.C., according to the statement. Aidan Dodson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol, could tell that it mentions Horemheb on several occasions and appears to discuss an event that happened during Horemheb’s reign. Dodson discovered that the giant engraving fits together like a jigsaw puzzle and sent a reconstruction to Live Science. Dodson said he will need to see better quality photos of the inscription to tell precisely what it says.

From General to Pharaoh

Horemheb "was in fact the highest general in King Tut's army during Tut's reign. He became king by marrying into the royal family, and being head of the army probably also didn't hurt his chances of becoming pharaoh, either," Ronald Leprohon, professor of Egyptology at the University of Toronto, told Live Science.

Precisely how long Horemheb’s reign as pharaoh lasted is a question that Egyptologists have long debated and the inscription, which Dodson says appears to include a date for an event that happened during Horemheb’s reign, may help answer this.

In addition to the giant jigsaw puzzle inscription a statement released by the ministry suggests that another inscription that dates to the reign of Ptolemy IV (reign 222–205 B.C.) was also discovered at Kom Ombo. Pictures of this inscription have not been released.

Editor's Note: This article was updated with new information suggesting the two stone slabs fit together into one giant engraving.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.