This Is the Oldest Known Inscription Bearing the Full Name of Jerusalem

Archaeologists have uncovered the oldest known instance of the word "Jerusalem" spelled out in full, on an ancient stone carving that was once part of an ancient pottery workshop, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, announced today (Oct. 9).

On earlier inscriptions, Jerusalem was spelled "Yerushalem" or "Shalem," rather than "Yerushalayim" (pronounced Yeh-roo-sha-La-yeem), as it is spelled in Hebrew today.

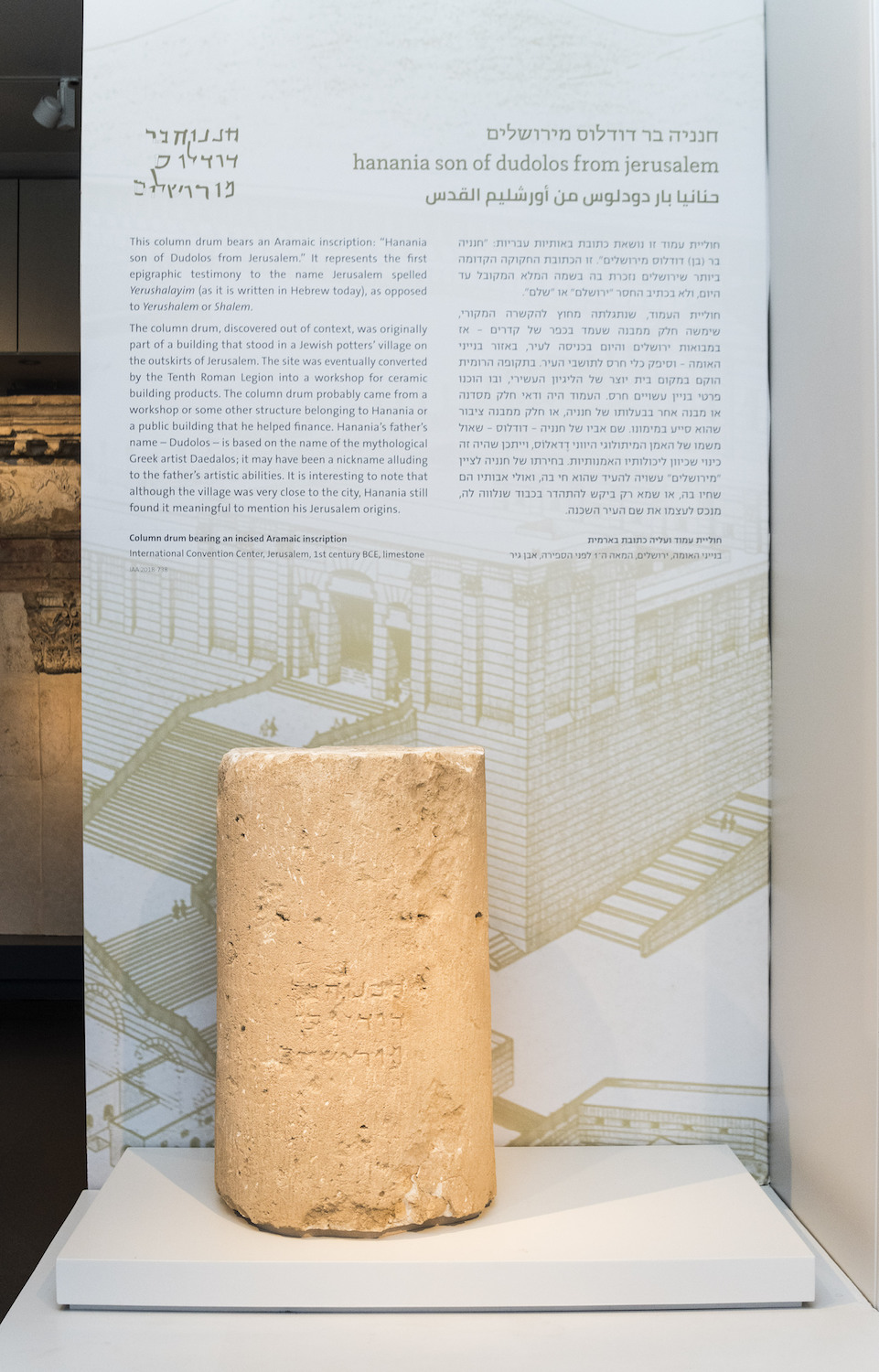

The carving — which was written in Aramaic and says "Hananiah son of Dodalos from Jerusalem" — dates to the first century A.D., making it about 2,000 years old, according to the IAA. [The Holy Land: 7 Amazing Archaeological Finds]

Archaeologists found the inscription during an archaeological survey preceding the construction of a new road near Jerusalem's International Convention Center, known as Binyanei Ha'Uma, this past winter. During the excavation, the archaeologists came across the foundations and stone columns of an ancient Roman structure.

One of the column drums (a cylindrical stone block that made up part of the column) had been repurposed from an earlier building, which likely dated to the time of Herod the Great's reign (37 to 4 B.C.), the archaeologists said. It was this column drum that had the inscription.

It's "unique" to see "the complete spelling of the name as we know it today, which usually appears in the shorthand version," Yuval Baruch, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Ronny Reich, a professor of archaeology at Haifa University in Israel, said in a statement. "This spelling is only known in one other instance, on a coin of the Great Revolt against the Romans (66 to 70 A.D.)."

Even in the Bible, in which "Jerusalem" appears 660 times, there are only five instances that spell out the full name, Baruch and Reich said. Moreover, these five instances, found in Jeremiah 26:18; Esther 2:6; 2 Chronicles 25:1; 2 Chronicles 32: 9; and 2 Chronicles 25: 1, were written at a relatively late date, they noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even though the newfound inscription refers to two people — Hananiah and Dodalos — it's unclear who those people were. "But it is likely that [Hananiah] was an artist-potter, the son of an artist-potter, who adopted a name from the Greek mythological realm, following Daedalus, the infamous artist," Dudy Mevorach, chief curator of archaeology at the Israel Museum, said in the statement.

Potter's paradise

In fact, the area where archaeologists uncovered the inscription appears to be a potter's quarter, the archaeologists said. The area contains vessels spanning a period of more than 300 years, from the Hasmonean period (140 to 116 B.C.) through to the late Roman era.

"This is the largest ancient pottery production site in the region of Jerusalem," Danit Levy, director of the excavations on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said in the statement.

The site included kilns, pools for preparing clay, plastered water cisterns, ritual baths and work spaces for drying and storing the vessels. During Herod's reign, the potters focused on creating cooking vessels, the archaeologists found. [Photos: Biblical-Era Fortress Discovered in Israel]

It appears that the potters were successful at their craft, because archaeologists found evidence of a small village nearby, whose economy likely depended on pottery production. The pots were sold in bulk to people living in and around Jerusalem, including at the city's gates to visiting pilgrims.

After Jerusalem fell in A.D. 70, when the Romans toppled the city, the potter's workshop resumed its work, but on a smaller scale, the archaeologists said. That ended in the early second century A.D., when the Roman's 10th Legion took over and established its own workshop, allowing the Romans to make rooftiles, bricks, pipes, tableware, cooking ware and storage vessels, the archaeologists said.

The stone carving, as well as the kilns from the potters' workshop, will go on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem tomorrow (Oct. 10), as part of a new exhibit that features artifacts from the capital. The exhibit will also showcase a Greek mosaic inscription from the sixth century A.D., unearthed near the Damascus Gate, which commemorated the construction of a public building — likely a hostel — in Jerusalem during the Byzantine period.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.