How This Time-Traveling Illusion Tricks Your Brain

Would you like to travel back in time, even if only for a moment?

While science hasn't cleared that hurdle yet (except, perhaps, for light particles), people can at least feel like they're traveling back in time by looking at two newly created illusions.

These illusions, which involve flashing lights and jarring buzzers, show that a new stimulus can change people's perceptions of a stimulus that happened a mere split-second prior, according a new study, published online Oct. 3 in the journal PLOS ONE.

This phenomenon is known as postdiction. Unlike prediction, when you try to forecast the future, postdiction occurs when a future stimulus influences how you see the past. [The Most Amazing Optical Illusions (and How They Work)]

"Illusions are a really interesting window into the brain," the study's first author, Noelle Stiles, a visitor in biology and biological engineering at the California Institute of Technology and a postdoctoral scholar-research associate at the University of Southern California, said in a statement. "By investigating illusions, we can study the brain's decision-making process."

While setting up the illusion, the researchers knew that in order to trick the brain, the stimuli had to occur nearly simultaneously, or under 200 milliseconds (one-fifth of a second) apart. The brain, they found, would try to make sense of a barrage of flashes and buzzers by synthesizing the different senses (sight and sound) using postdiction.

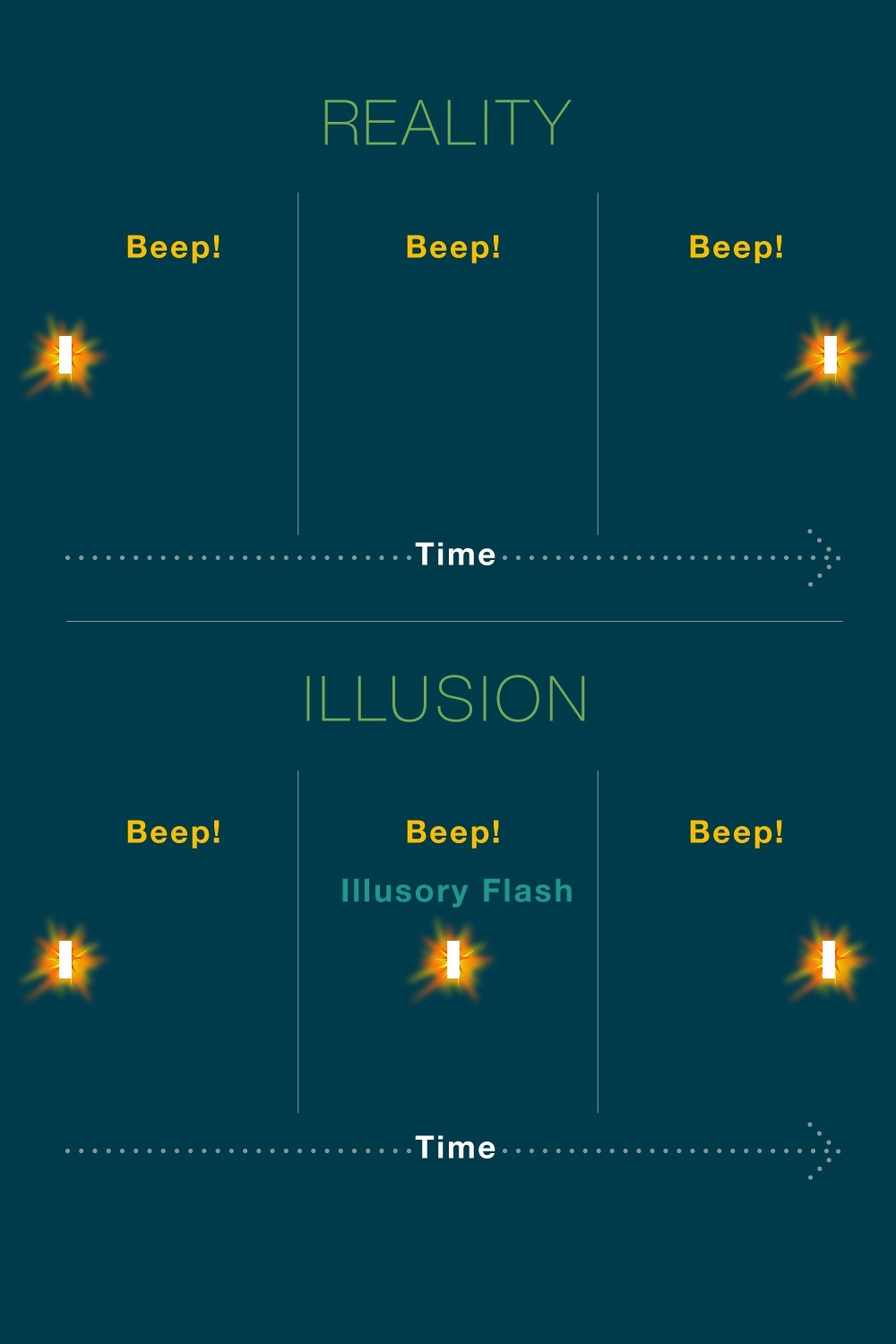

In the first illusion — called the Illusory Rabbit — the researchers made a video that had three parts: (1) a beep and a flash on the left side of the screen, followed by (2) a beep, and then (3) followed by another beep and a flash on the right side of the screen. A mere 58 milliseconds separated each part of the video.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, even though there are only two flashes, most people perceived three. There is no flash on the second beep, but people tended to report seeing a flash in the middle of the screen when the second beep buzzed. You can see it for yourself in the below video.

Given that the illusory flash is perceived between the left and right flashes, it appears that the brain is using postdictive processing to fill in the gap, the researchers said.

"When the final beep-flash pair is later presented, the brain assumes that it must have missed the flash associated with the unpaired beep and quite literally makes up the fact that there must have been a second flash that it missed," Stiles said. "This already implies a postdictive mechanism at work. But even more importantly, the only way that you could perceive the shifted illusory flash would be if the information that comes later in time — the final beep-flash combination — is being used to reconstruct the most likely location of the illusory flash as well."

The second illusion is dubbed the Invisible Rabbit. In this illusion, three lights flash across a screen — first on the left, next in the middle and finally on the right, with beeps sounding on the first and third flashes. However, most people do not see the second flash, simply because it didn't have a buzzer accompanying it.

This is actually a big deal for scientists. By showing that sound can lead to a visual illusion, the research team showed how the brain combines senses over space and time to generate an integrated sense of perception.

"The significance of this study is twofold," the study's senior author, Shinsuke Shimojo, a professor of experimental psychology at Caltech, said in the statement. "First, it generalizes postdiction as a key process in perceptual processing for both a single sense and multiple senses," Shimojo said, referring to sight in the first experiment and sight and sound in the second.

He added, "Postdiction may sound mysterious, but it is not — one must consider how long it takes the brain to process earlier visual stimuli, during which time subsequent stimuli from a different sense can affect or modulate the first."

The rabbit experiments also reveal that "these illusions are among the very rare cases where sound affects vision, not vice versa, indicating dynamic aspects of neural processing that occur across space and time," Shimojo said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.