Do Canadian Carvings Depict Vikings? Removing Mammal Fat May Tell

Carvings uncovered in the Canadian Arctic may be the earliest portraits of the Vikings created in the Americas. But archaeologists have been puzzling over whether the artwork really shows the infamous seafarers.

Now, scientists think a simple, flammable liquid called acetone could help solve this mystery by removing sea-mammal oil and fat from these artifacts and other artifacts found near them. Until now, those contaminants have prevented scientists from getting an accurate radiocarbon date, according to a paper published in the August issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Oily problem

The Vikings, along with other peoples who lived in arctic or subarctic environments, used oils and fat from sea mammals for a variety of purposes, including preparing food and cooking. The substances interfere with radiocarbon dating, because rather than getting the date of the artifact, you may get the date for the oil and fat covering the object, study authors Michele Hayeur Smith, Kevin Smith and Gørill Nilsen wrote in the new paper.

Hayeur Smith is a research associate at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology at Brown University in Rhode Island, where Smith is chief curator. Nilsen is an archaeology professor at the Arctic University of Norway. [In Photos: Viking Settlement Discovered at L'Anse aux Meadows]

Arctic environments often have little soil accumulation, making it easier for oil and fat to get on artifacts lying in the ground. "Across the Arctic, where most sites are shallow, reoccupation episodes thousands of years apart may be separated from one another by mere centimeters of soil development," the scientists wrote. This means that artifacts can intermix with oil and fat from a variety of time periods making it hard to tell when artifacts date to.

Acetone to the rescue

To solve this radiocarbon-dating problem, Nilsen developed a few methods to remove sea-mammal oil and fat from artifacts. To test the methods, Nilsen used samples of wood dated, via radiocarbon methods, to around 42,000 years ago. She drenched those samples in modern-day sea-mammal oil.

Her first method used a mix of acids and alkalis, but it failed, resulting in dates of 16,000 years ago. That suggested the process hadn't stripped off all of the oil and fats, Nilsen said. She then tried two acetone-based methods, and both were successful.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Solving mysteries

The ability to remove sea-mammal oils and fats from artifacts is a "major breakthrough" for archaeologists studying the Vikings and other Arctic peoples, the three researchers said. [Fierce Fighters: 7 Secrets of Viking Seamen]

The new method has already helped solve one mystery, the scientists said. They used it to radiocarbon-date samples of spun yarn found by archaeologists at various sites in the Canadian Arctic.

A long-running debate disputes whether the Vikings taught indigenous peoples in the Canadian Arctic how to spin yarn when the invaders arrived in the region around 1,000 years ago. The team found that some of the spun yarn dates back at least 2,000 years, long before the Vikings arrived in the area. This shows that the indigenous peoples in the Canadian Arctic developed yarn-spinning technologies without any help from the Vikings, the scientists said.

Wooden carvings

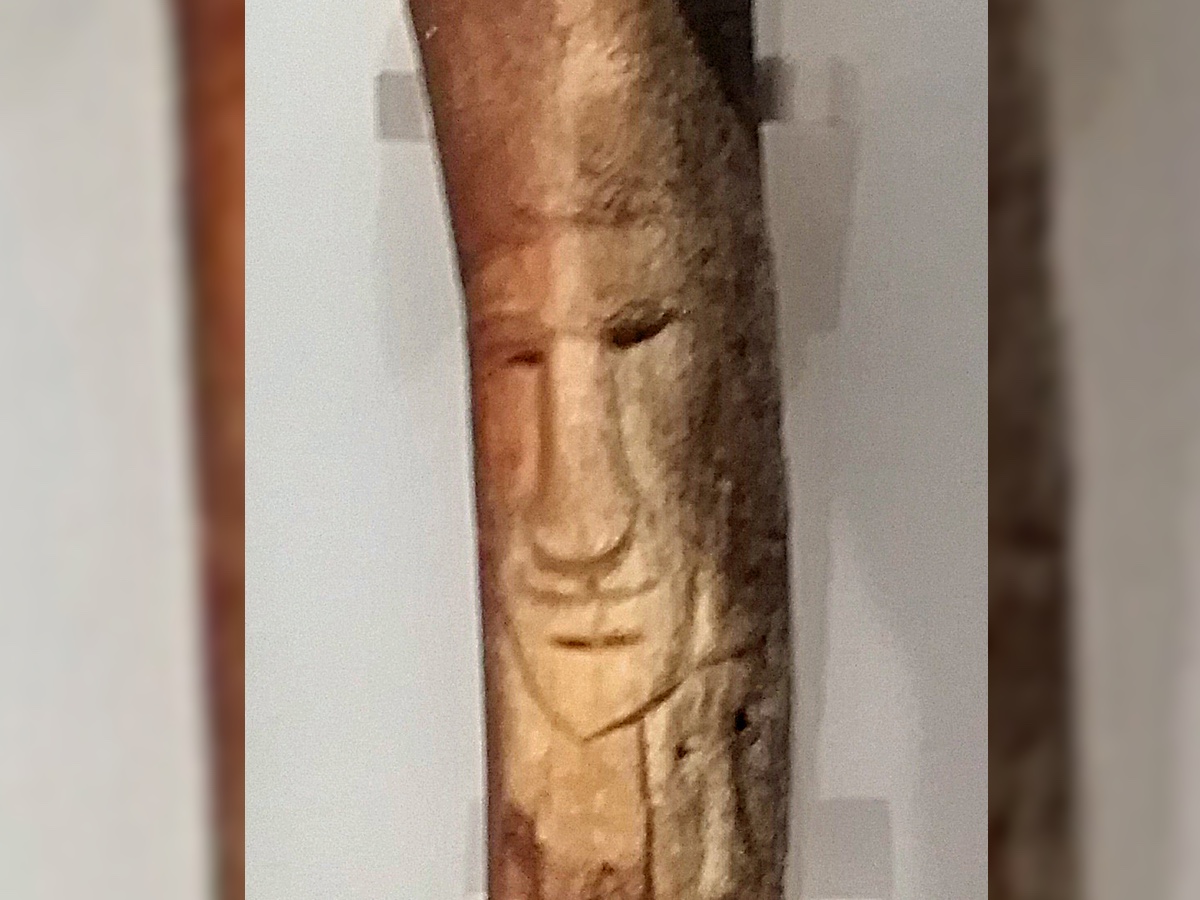

Now it may be possible to solve the mystery of the wooden carvings from the Canadian Arctic. These carvings, which were created by the region's indigenous peoples, have features that some scholars believe identify the objects as Viking.

Researchers haven't radiocarbon-dated any of the wooden carvings so far, Hayeur Smith told Live Science, adding that the initial round of radiocarbon dating focused on textiles.

One of the carvings was excavated in the 1970s at the Okivilialuk site on southern Baffin Island.Two textiles found near the Okivilialuk carving date back to the 16th century, suggesting that the carving may also date back to that time, the scientists said. This carving may not show a Viking, but it could show someone from one of Sir Martin Frobisher's expeditions to the Canadian Arctic in the 1570s, the researchers said.

Researcher Patricia Sutherland urged caution on these findings, saying that excavation records indicate that the Okivilialukcarving was found at a lower level (meaning it was created earlier) than the textiles. Sutherland is a research associate at Carleton University in Canada who has excavated extensively in the Canadian Arctic but is not involved in the new research. That finding, Sutherland said, suggests that the carving may date back to earlier than the 16th century meaning it could show Vikings.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.