11 fascinating facts about our Milky Way galaxy

Our Milky Way Galaxy

How much do you know about the city you live in? Sure, you've got your favorite restaurants and the best way to avoid traffic during rush hour, but it's unlikely you know the details of every urban nook and cranny. The same goes for the galaxy you live in, the Milky Way.

Our celestial home is an awe-inspiring place full of stars, supernovas, nebulas, energy and dark matter, but many aspects of it remain mysterious, even to scientists. For those seeking to better know their own place in the universe, here are 11 enlightening facts about the Milky Way.

The MIlky Way's name is ancient

Before the advent of electric lights, everybody on Earth had an unobstructed view of the night sky. The enormous milky band of stars crossing it was impossible to miss. Ancient peoples gave different names to the cloud-like structure of our galaxy, but our modern version derives from the Greeks, who had a myth about the infant Hercules being brought to the goddess Hera, who nursed him while she was asleep. When she awoke and pulled away, her breast milk spilled across the heavens. The source of the Greek name itself has been lost to the ages, Matthew Stanley, a professor of the history of science at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at New York University, previously told Live Science. "It's one of those terms that's so old that its origin is generally forgotten by now."

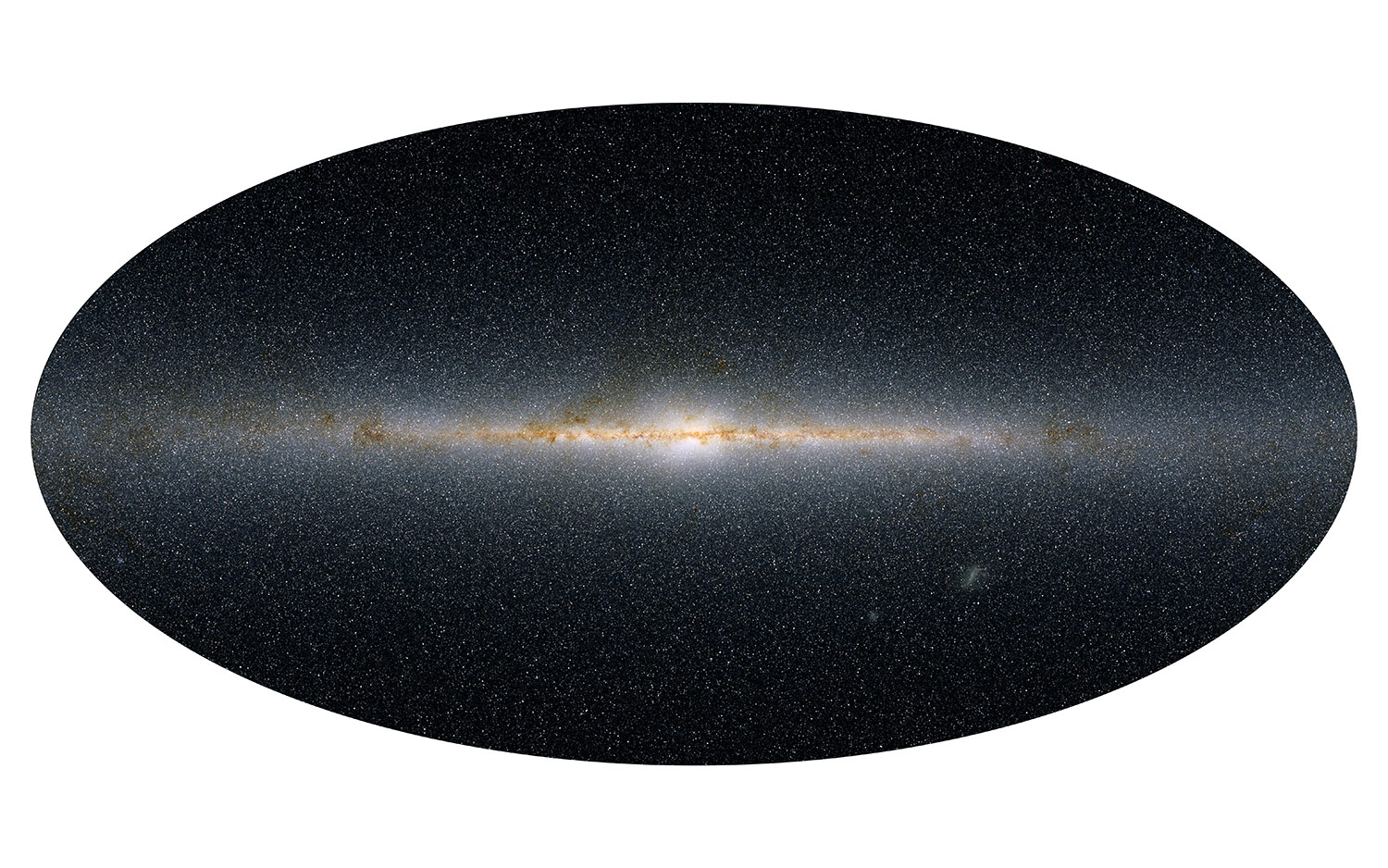

We're not sure exactly how many stars are in the Milky Way

Counting stars is a tedious business. Even astronomers argue over the best way to do it. Their telescopes see only the brightest stars in our galaxy, and many are hidden by obscuring gas and dust. One technique to estimate the stellar population of the Milky Way is to look at how fast stars are orbiting within it, which gives an indication of the gravitational tug, and therefore the mass, of the galaxy. Divide the galactic mass by the average size of a star and you should have your answer. But as David Kornreich, an astronomer at Ithaca College in New York, told Live Science's sister site Space.com, these numbers are all approximations. Stars vary widely in size, and many assumptions go into estimating the number of stars residing in the Milky Way. The European Space Agency's Gaia satellite has mapped the location of 1 billion stars in our galaxy, and its scientists believe this represents 1 percent of the total, so perhaps the Milky Way contains about 100 billion stars. [Large Numbers That Define the Universe]

Nobody knows how much the Milky Way weighs

On a related note, astronomers are still unsure exactly how much our galaxy weighs, with estimates ranging from 700 billion to 2 trillion times the mass of our sun. Getting a better grasp is no easy task. Most of the Milky Way's mass — perhaps 85 percent — is in the form of dark matter, which gives off no light and so is impossible to directly observe, according to astronomer Ekta Patel of the University of Arizona in Tucson. Her recent study looked at how strongly our galaxy's humongous mass gravitationally tugs on smaller galaxies orbiting it and updated the estimate of the Milky Way's mass to 960 billion times the mass of the sun, Live Science previously reported.

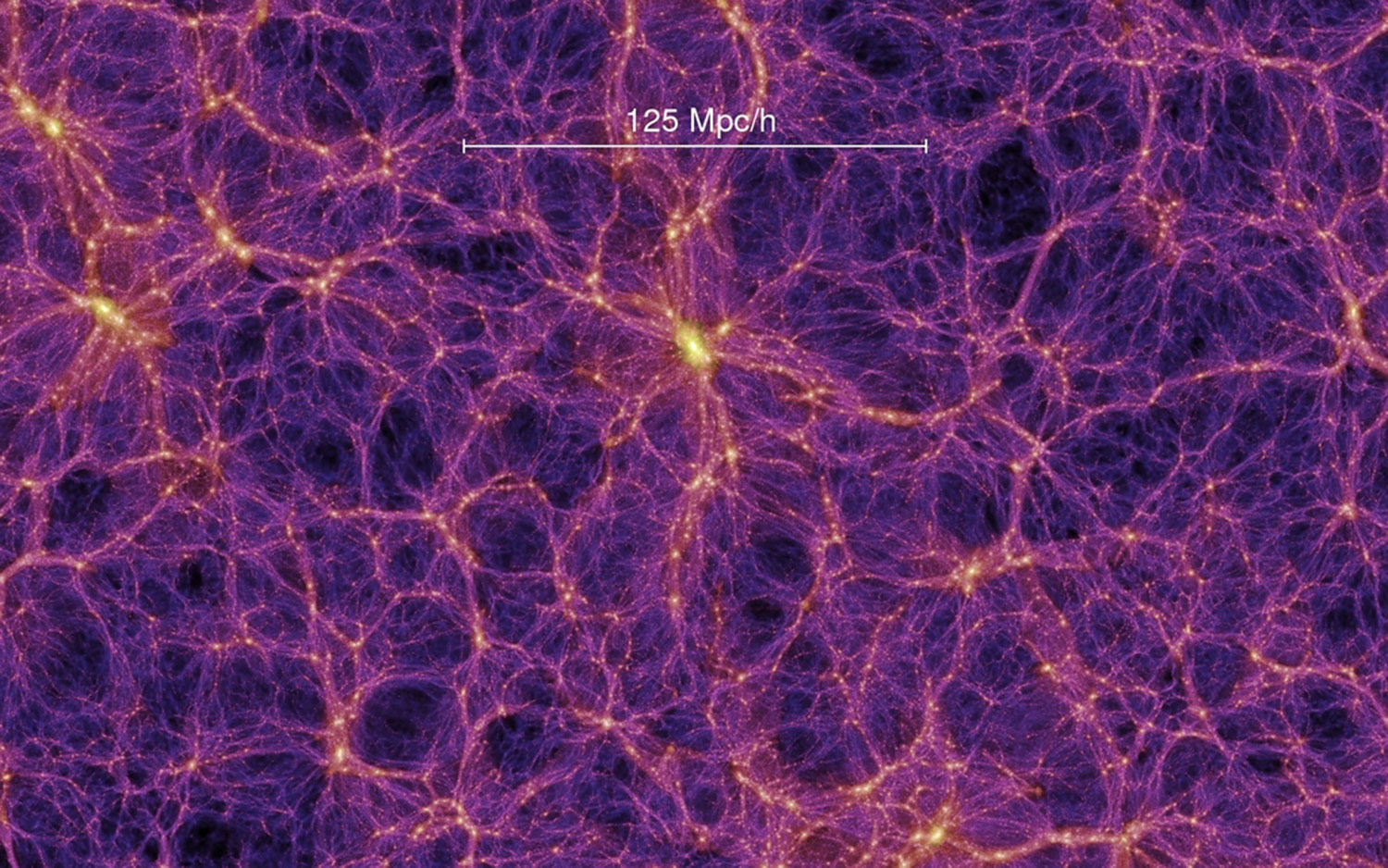

The Milky Way is probably in a big, empty spot in the universe

Several studies have indicated that the Milky Way and its neighbors are living out in the boonies of the cosmos. From afar, the large-scale structure of the universe looks like a colossal cosmic web, with string-like filaments connecting dense regions separated by enormous, mostly empty voids. The emphasis in that last sentence should be on "mostly empty," since our own galactic abode seems to be an inhabitant of the Keenan, Barger and Cowie (KBC) Void, named after three astronomers who identified it in a 2013 study in The Astrophysical Journal. Last year, a separate team looked at the motion of galaxies in the cosmic web to provide additional confirmation that we're floating in one of the big, empty areas, Live Science previously reported.

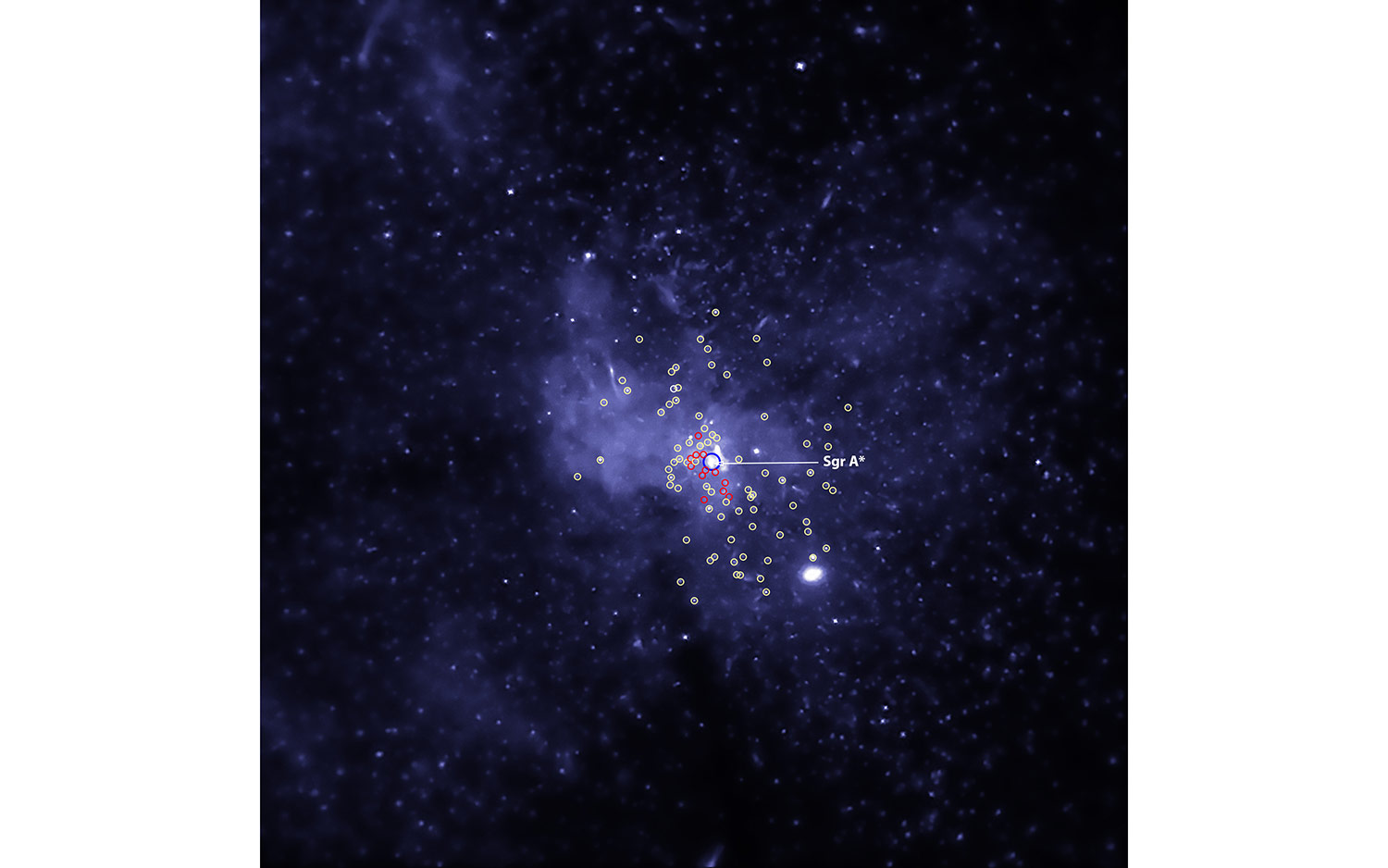

Astronomers are trying to photograph the monster black hole at the Milky Way's center

Lurking in the heart of our galaxy is a hungry behemoth, a gigantic black hole with the weight of 4 million suns. Scientists know that it's there because they can trace the paths of stars in the Milky Way's center and see that they seem to orbit a supermassive object that can't be seen. But in recent years, astronomers have been combining observations from multiple radio telescopes to try and get a glimpse of the environment surrounding the black hole, which is packed with gas and dust spinning around the black hole's maw. The project, called the Event Horizon Telescope, expects to have preliminary images of the black hole's edge in the coming months, according to the team's blog. [Stephen Hawking's Most Far-Out Ideas About Black Holes]

Small galaxies orbit the Milky Way and sometimes crash into it

When Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan sailed through the Southern Hemisphere in the 16th century, he and his crew were among the first Europeans to report on circular clusters of stars in the night sky, according to the European Southern Observatory. These clusters are actually small galaxies that orbit our Milky Way like planets around a star, and they have been named the Small and Large Magellanic clouds. Many such dwarf galaxies orbit ours — and sometimes they get eaten by our massive Milky Way. Earlier this year, astronomers used new data from the Gaia satellite that showed millions of stars in our galaxy moving in similar narrow, "needle-like" orbits, suggesting they all originated from an earlier dwarf galaxy dubbed "the Gaia Sausage," as Live Science reported at the time.

The Milky Way is full of toxic grease

Swirling through the mostly empty space between stars in our galaxy is a bunch of dirty grease. Oily organic molecules known as aliphatic carbon compounds are produced in certain types of stars and then are leaked out into interstellar space. A recent study found that these grease-like substances could account for between a quarter and one-half of the Milky Way's interstellar carbon — five times more than previously believed, as Live Science reported in June. Though strange, the findings are cause for optimism, according to researchers. Because carbon is an essential building block of living things, finding it in abundance throughout the galaxy could suggest that other star systems harbor life.

The Milky Way is going to crash with its neighbor in 4 billion years

Sad to say, but our galaxy isn't going to be here forever. Astronomers know that we are currently speeding toward our neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy, at around 250,000 mph (400,000 km/h). When the crash comes, in about 4 billion years, most research has suggested that the more massive Andromeda galaxy would swallow up our own and survive. But in a recent study, astronomers reweighed Andromeda and found that it was roughly equivalent to 800 billion suns, or about on par with the Milky Way's mass, as Live Science previously reported. That means that exactly which galaxy will emerge less scathed from the future galactic crash remains an open question.

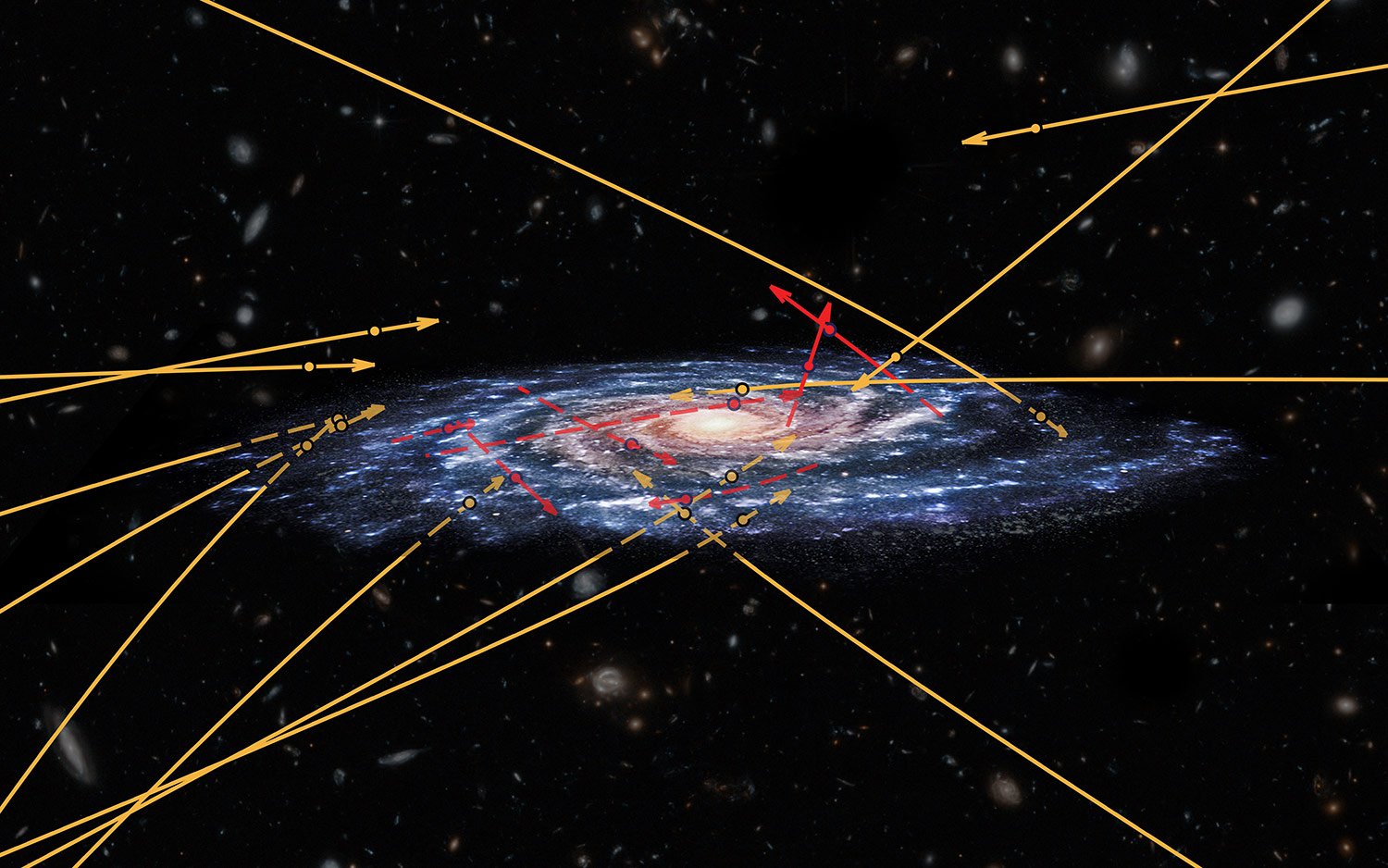

Stars from our galactic neighbors are racing toward the Milky Way

Movie stars in films are known to swap spit, but who knew that galaxies in the universe sometimes swap stars? Researchers were recently searching for hypervelocity stars, which get thrown at mind-bending speeds from the Milky Way after interacting with the giant black hole in its center. What they found was even stranger — rather than flying away from our galaxy, most of the fast stars they spotted were barreling toward us. "These could be stars from another galaxy, zooming right through the Milky Way," Tommaso Marchetti, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands, said in a statement. In the study, which was published Sept. 20 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the authors suggest that these odd stars could have originated in the Large Magellanic Cloud or some other galaxy farther away and write in their paper that the discovered objects "may constitute the tip of the iceberg" of a large population of similar stars.

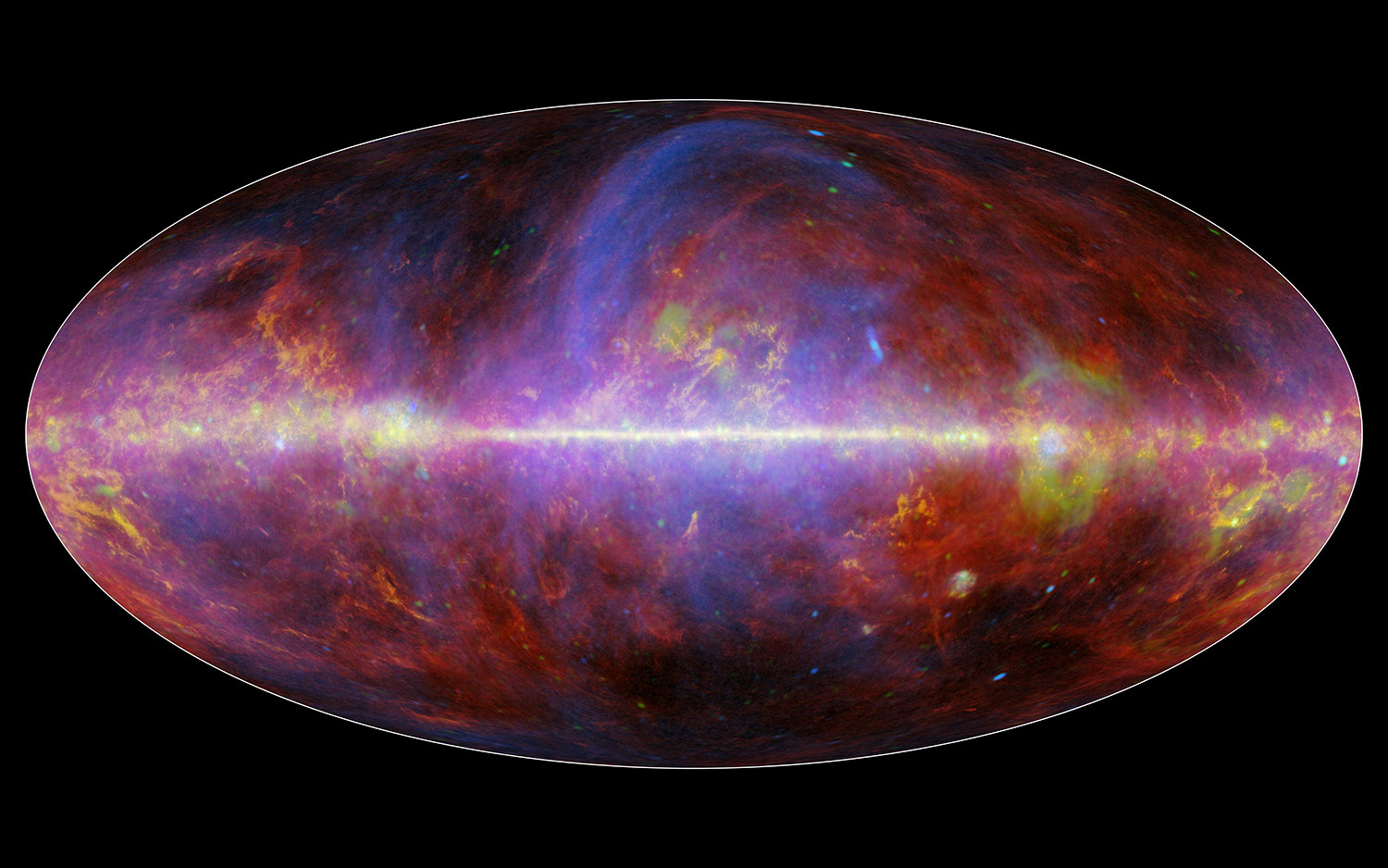

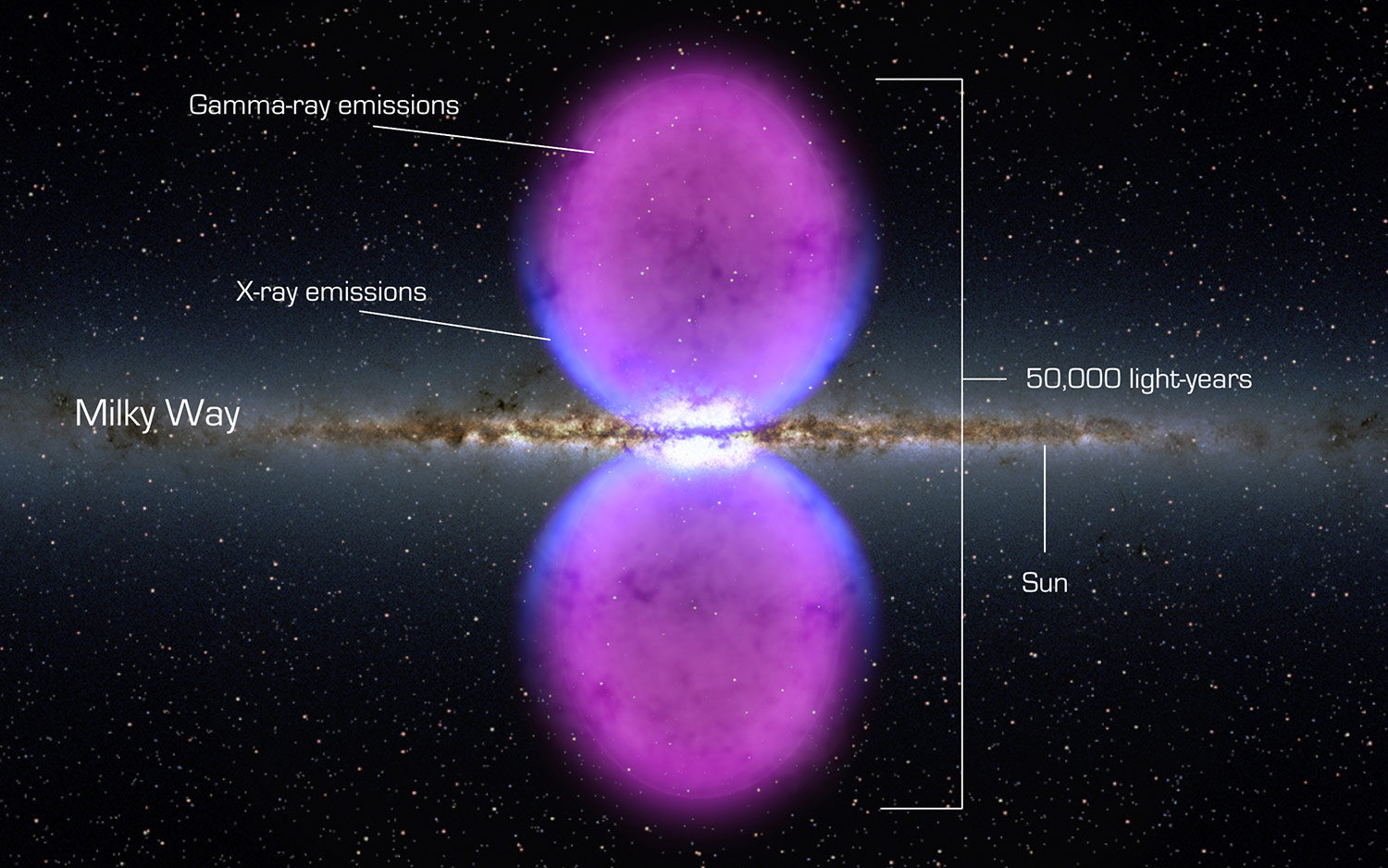

There are mysterious bubbles arising out of the Milky Way

Imagine discovering that your living room, which you've seen a million times before, contained a previously unnoticed elephant. That's more or less what happened to scientists in 2010 when they uncovered gigantic, never-before-seen structures stretching for 25,000 light-years above and below the galaxy. Named 'Fermi bubbles' after the telescope that found them, these gamma-ray-emitting objects have defied astronomers' explanations ever since. Last year, a team gathered evidence suggesting that the bubbles are the aftermath of an energetic event 6 million to 9 million years ago, when the supermassive black hole in the galactic center swallowed a huge clump of gas and dust and burped out the giant, glowing clouds, according to NASA.

Our galaxy is being bombarded with bizarre energy pulses from the other side of the universe

Over the last decade, astronomers keep detecting odd flashes of light coming at them from the distant cosmos. Known as fast radio bursts (FRBs), these mysterious signals have no agreed-upon explanation. Despite knowing about them for more than 10 years, researchers had until recently captured only 30 or so examples of these FRBs. But in a recent study, Australian scientists managed to find 20 more FRBs, nearly doubling the number of known objects, as Live Science previously reported. While they still don't know the odd flashes' origin, the team was able to determine that the light had traveled through several billion light-years of gas and dust, which imparted telltale signs on the signal, suggesting that the FRBs were coming from quite a long way off.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.