One of the World's Oldest and Largest Organisms Is Dying, and It's Mostly Our Fault

One of the largest organisms in the world, a Utah forest of genetically identical trees, is slowly being devoured by deer.

The Pando quaking aspen colony, also known as the "Trembling Giant," has likely survived for thousands of years. But about 80 percent of it is in a perilous state, according to a new paper published today (Oct. 17) in the journal PLOS One.

The trembling giant, weighing 13 million lbs. (5.9 million kilograms) and covering 106 acres (0.42 square kilometers) of Utah's Fishlake National Forest, consists of over 47,000 genetically identical stems that grow from a single underground parent clone. [Quaking Aspen: Trees of the Mountain West]

In this new study, a group of researchers measured the health of various parts of the forest, such as by counting the number of living versus dead trees, counting the number of new stems and tracking the feces of animals that dropped in for a bite. They found that the biggest obstacle to the strongest indicator of the forest's health — whether new sprouts could survive — was mule deer.

It's natural that the older stems are dying off, lead author Paul Rogers, the director of the Western Aspen Alliance and adjunct associate professor at Utah State University,told Live Science. What's unnatural is that new stems aren't growing, he said. For the past couple of decades, mule deer and cattle have been eating all the new stems that sprout from the underground mama aspen. In most areas, there's no "young or middle-aged trees at all," he said. So the forest, to use human terms, is made up "entirely of very elderly senior citizens," Rogers said.

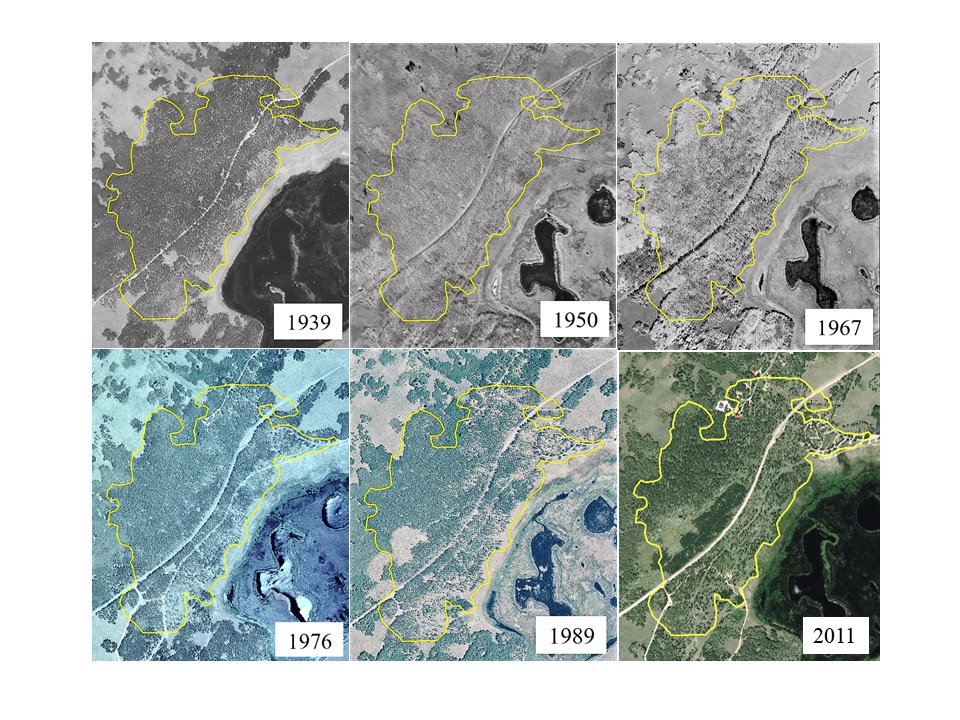

Aerial photographs of the decline

Rogers and his team also compared aerial photographs of the area that spanned 72 years and found that the aspen forest has been thinning. Back in 1939, the tree crowns all touched, but starting in the 1970s, "you see a lot of spaces between the trees," he said. This means that the old trees are dying and new ones aren't coming in to fill in the gaps.

Part of the problem is that game such as mule deer do not have natural predators in the area anymore. In the early 1900s, humans killed off most natural predators, such as wolves and grizzly bears, Rogers said. Now, most of the grounds in Pando are set aside for recreational uses like camping, where the browsers are protected from hunting. "The deer know that very early on, and they find it a safe harbor."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But really, "Pando is failing because of human decisions," Rogers said. "Humans control wild animals, particularly wild-game species like deer and elk."

There is one part of the trembling giant that is thriving. This area was fenced in around 2013 and within five years, thousands of stems — some 12 to 15 feet (3.6 to 4.5 m) tall — have been growing per acre, Rogers said. Here, the fence seems to be working. Half of the area that the aspen clone takes up is unfenced and easily accessible by the mule deer and cattle. Around 30 percent of the area is fenced in with an 8-foot-tall (2.4 meters) fence, Rogers said. But "the fence is not doing its job, so it's also in a poor state," he said. "Somehow, the animals are still getting in — it's a bit of a mystery to us," he said. He thinks the mule deer (not the cattle) are jumping it.

"We need to help control the animals — both deer and cattle — and give Pando a break so that it can recover," Rogers said. This can be done by culling their numbers, restricting them with properly working fences or keeping them moving out of the area, as predators traditionally did, he said.

"We're not talking about just the tree, but we're talking about all the plants and animals dependent on it," Rogers said. "We can't manage wildlife and forest independently, we have to manage them in concert and in coordination with each other."

And the approaches that work to protect Pando could be extended to aspens around the world, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.