Pompeii Graffiti May Rewrite Time Line of Vesuvius Eruption

Graffiti scribbled on the wall of a Pompeii house that was being renovated in A.D. 79 may help solve a long-standing mystery about when Mount Vesuvius erupted that year, burying the Roman settlement in ash.

There is little doubt among archaeologists and historians that Vesuvius erupted and destroyed Pompeii in the year A.D. 79. But experts still debate the time of year when the volcano blew its top.

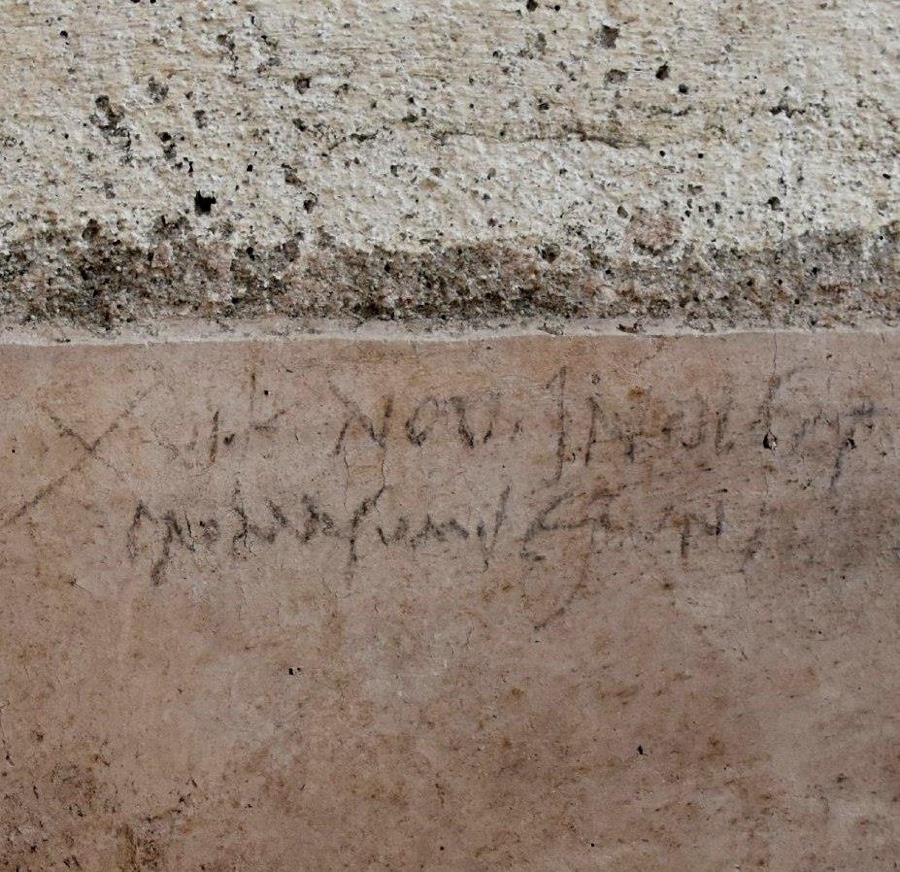

The newly discovered graffiti, written in Latin, indicates that it was created on a date that, on our calendar, corresponds to Oct. 17. These markings refer to an unnamed individual who overindulged in food. The writing includes no year, but the text was found in part of a house that was undergoing renovation at the time the eruption occurred, wrote a team of archaeologists that conducted the investigation in a statement released Oct. 16 by the Pompeii Parco Archeologico, a government agency in charge of archaeological and conservation work at Pompeii. [Photos: The Bones of Mount Vesuvius]

Archaeologists can tell that the room was being renovated as the flooring was incomplete and there was undecorated plaster on the walls.

"Furthermore, since it [the graffiti] was done in fragile and evanescent charcoal, which could not have been able to last long, it is highly probable that it can be dated to the October of A.D. 79," the statement said.

Long-standing debate

Archaeologists and historians have long debated when, exactly, Mount Vesuvius blew up and destroyed Pompeii. Some copies of a letter written by Pliny the Younger (who lived around A.D. 61-113) to Tacitus (a Roman historian who lived A.D. 56-120) say that the eruption happened on a date that corresponds to Aug. 24.

However, multiple lines of scientific evidence suggest that the eruption occurred in the autumn rather than in August, a team of scientists led by Giuseppe Rolandi, a professor of Earth sciences at the University of Naples, wrote in a paper published in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research in January 2008.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For instance, the dispersion of tephra, a type of debris produced by a volcanic eruption, closely matches wind patterns seen around Pompeii in the autumn rather than in August, Rolandi's team reported in the paper. The researchers also noted that organic finds at Pompeii suggested that crops harvested in the autumn, such as grapes and pomegranates, had been harvested at Pompeii before Vesuvius blew its topup.

Rolandi's team additionally noted that a coin found at Pompeii bears an inscription suggesting that the money was minted no earlier than September of A.D. 79. The researchers further noted that not all surviving copies of Pliny the Younger's letter show the Aug. 24 date, meaning that the people who copied down Pliny's letters in ancient times may have made an error.

Understanding disease

Pompeii, and the other communities destroyed by Vesuvius, preserve a snapshot in time, a point in history where many people died, suddenly, from a major disaster. This gives scientists the opportunity to see what diseases people were suffering from before they were killed in the eruption. However, knowing whether this snapshot in time happened in August or in the autumn can make a difference in understanding disease patterns, wrote Kristina Killgrove, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in an article she wrote recently in Forbes.

"Since many diseases are seasonal, or at least [reach their] peak in certain seasons, like the current flu season, a difference of two months — from late summer to early fall — is incredibly important to researchers like me, who deal with the analysis of organic remains," Killgrove wrote. Her research focuses on the remains of people who died when a giant Roman villa at the site of Oplontis was destroyed by Vesuvius. [The 11 Biggest Volcanic Eruptions in History]

For instance, if scientists know that that the eruption happened in autumn and Killgrove finds a high rate of a particular disease at Oplontis, she can then study whether the spread of the disease had anything to do with the autumn season.

"This new graffito may not rewrite history, but I am more convinced than ever that an early fall date for the eruption is the one I should use when formulating hypotheses about and interpreting data from the human skeletal remains," Killgrove added in her article.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.