Exquisitely Preserved Lungs from 120 Million Years Ago Stun Scientists Studying Early Bird

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Ancient organs rarely fossilize, so paleontologists were stunned to find the incredibly well-preserved remains of a lung that belonged to bird from the dinosaur age.

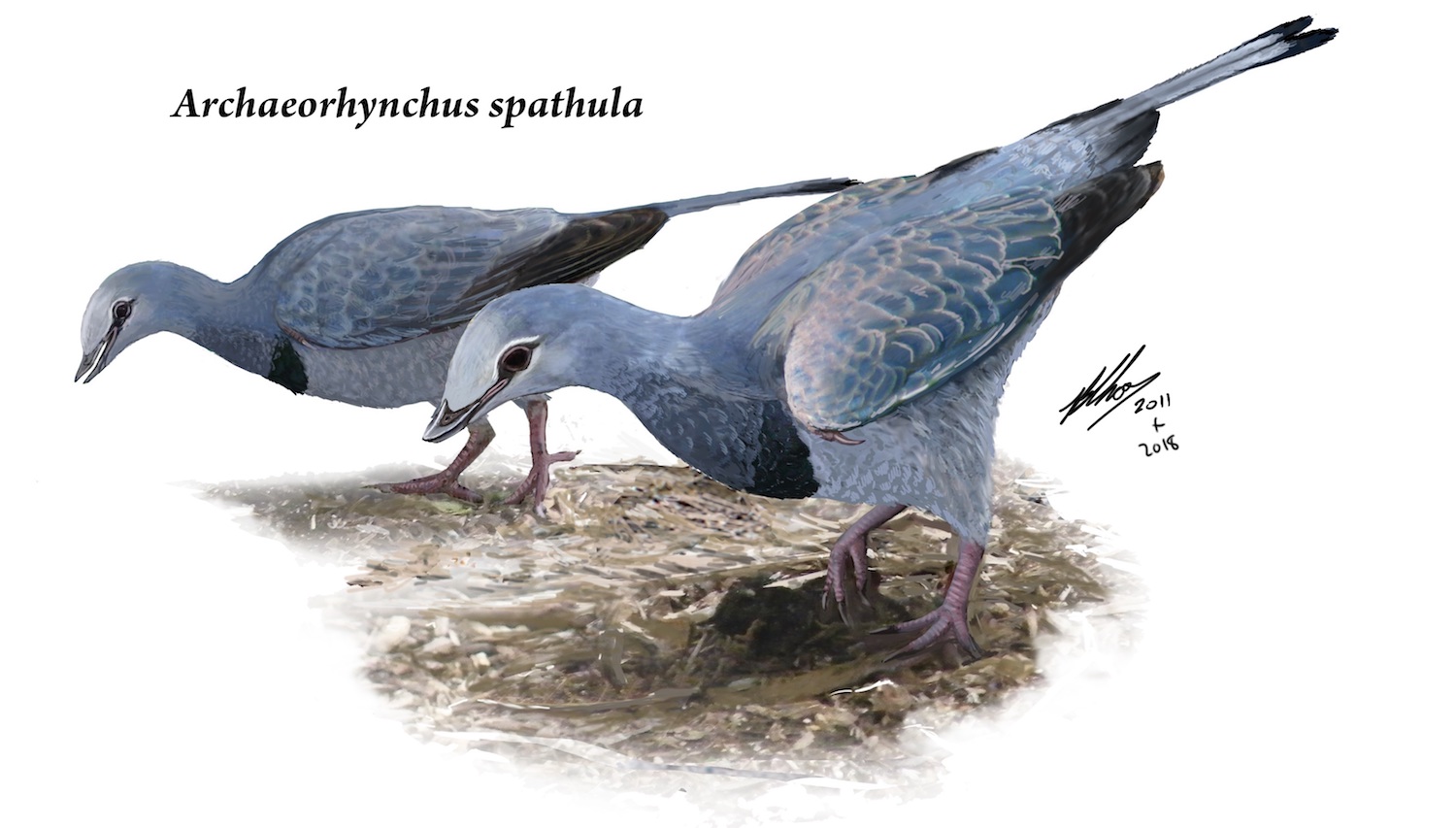

Initially, scientists were excited to describe the specimen of Archaeorhynchus spathula, a bird that lived about 120 million years ago, because its fossil had exquisitely preserved feathers, including a unique pintail that isn't seen in any other Cretaceous bird, but is common in birds nowadays.

A closer inspection, however, revealed that the bird's lungs had also fossilized, meaning the paleontologists had discovered the oldest "informative" fossilized lung on record (more on that later) and the oldest fossilized lung ever seen in a bird fossil, said study co-lead researcher Jingmai O'Connor, a professor with the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. [Tiny Dino: Reconstructing Microraptor's Black Feathers]

The fossil itself is from the early Cretaceous Jehol Lagerstätte formation in northeastern China, but O'Connor and her colleagues found it at the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, in Pingyi, where an avid fossil collector houses the thousands of bird fossils he's purchased over the decades.

This is the fifth described A. spathula specimen — a toothless, pigeon-size bird — but it's by far the best preserved, O'Connor said. That's especially because of the speckled, white material in its chest cavity that appears to be a fossilized lung.

The finding reveals that the lung structures in early birds are similar to the lungs of modern birds, the researchers said. This means that A. spathula likely had unidirectional airflow in its lungs — the air that flowed in was largely fresh and full of oxygen, unlike the air in mammals' lungs, which is mixed with both new and previously breathed air, meaning it has a lower oxygen content.

"Lungs of birds are very different from our lungs and [had] much more complex structures," P. Martin Sander, a paleontologist at the University of Bonn in Germany who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email. "They are kind of like a bag pipe, with an air management system (the air sacs) separated from the gas exchanger (the lung proper) which is preserved here."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Living crocodilians also have lungs with unidirectional airflow, and paleontologists considered it to be ancestral in early feathered dinosaurs. But evidence for such a lung structure in an early bird has been elusive, until now.

Deep dive

To get a better look at the supposed lung remains, "we went and extracted some samples, put them in the SEM [scanning electron microscope] and — boom — lung tissue," O'Connor told Live Science. Because O'Connor specializes in skeletal (not organ) anatomy, she roped in John Maina, a professor of zoology at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa, who is an expert on the lungs of living birds.

"I was like, 'Look, do you think this is lung tissue? If you do think it is, then none of us digging-in-the-dirt paleontologists can argue with you,'" O'Connor said. Maina's contribution was so critical, that he became a co-researcher on the study.

An analysis of the tissue showed that it contained structures that resemble blood capillaries, which absorb oxygen to help power the highly energetic flight of birds. "Avian flight is the most physically demanding form of locomotion, so you need a lot of oxygen for it," O'Connor said. [Photos: Dinosaur-Era Bird Sported Ribbon-Like Feathers]

It's possible that this unique structure was unique to Ornithuromorpha, a clade (group) of ancient birds that survived the mass extinction about 66 million years ago and includes today's living birds. "Maybe this specialization was only in that clade and was one of the many factors that allowed [their] survival," O'Connor said.

What's more, it appears that the fossilized lung was embedded in the bird's ribs, just as bird lungs are today. Unlike human lungs, which expand with every breath, bird lungs are rigid, so they can easily inhale and exhale at the same time, O'Connor said.

The tissue doesn't appear to be leftover stomach contents, as those usually preserve as black, carbonized organic matter, she noted. Moreover, the preserved tissue is paired, just like a modern lung. There are no other paired organs that it could be, and it's likely not the liver (which is lobed) because that organ has a high iron content and usually preserves as red, O'Connor said.

However, this specimen isn't the oldest lung on record. That honor goes to Spinolestes, an early Cretaceous mammal that has fossilized lungs about 5 million years older than the newly analyzed bird. But those lung fossils didn't preserve any microstructure and don't provide much information about Spinolestes, other than that it likely had a muscular diaphragm. So, O'Connor is calling the A. spathula fossil "the first informative lung remains," because they shed light on bird evolution.

The lung findings are "cool stuff," because it shows"what the lung of an early bird looked like," Sander said. However, because it's so rare to see a fossilized organ, more work is needed to verify that this is a lung, he said.

"We should apply various other analytical techniques to confirm that the area in the fossil really is lung," he said. "But I would not be surprised if lung can fossilize because of its high iron content because the lung is rich in blood."

The research was presented here at the 78th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting yesterday (Oct. 18). It will be published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday (Oct. 22).

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.