In Photos: Eerie Zoo Animal Skeletons, in X-Rays

Spooky, scary skeletons

Are x-rays of animals gorgeous or creepy? Maybe a little of both. The Oregon Zoo recently captured a series of Halloween-ready X-rays showcasing some of their animals. Here, a three-banded armadillo displays its built-in suit of armor.

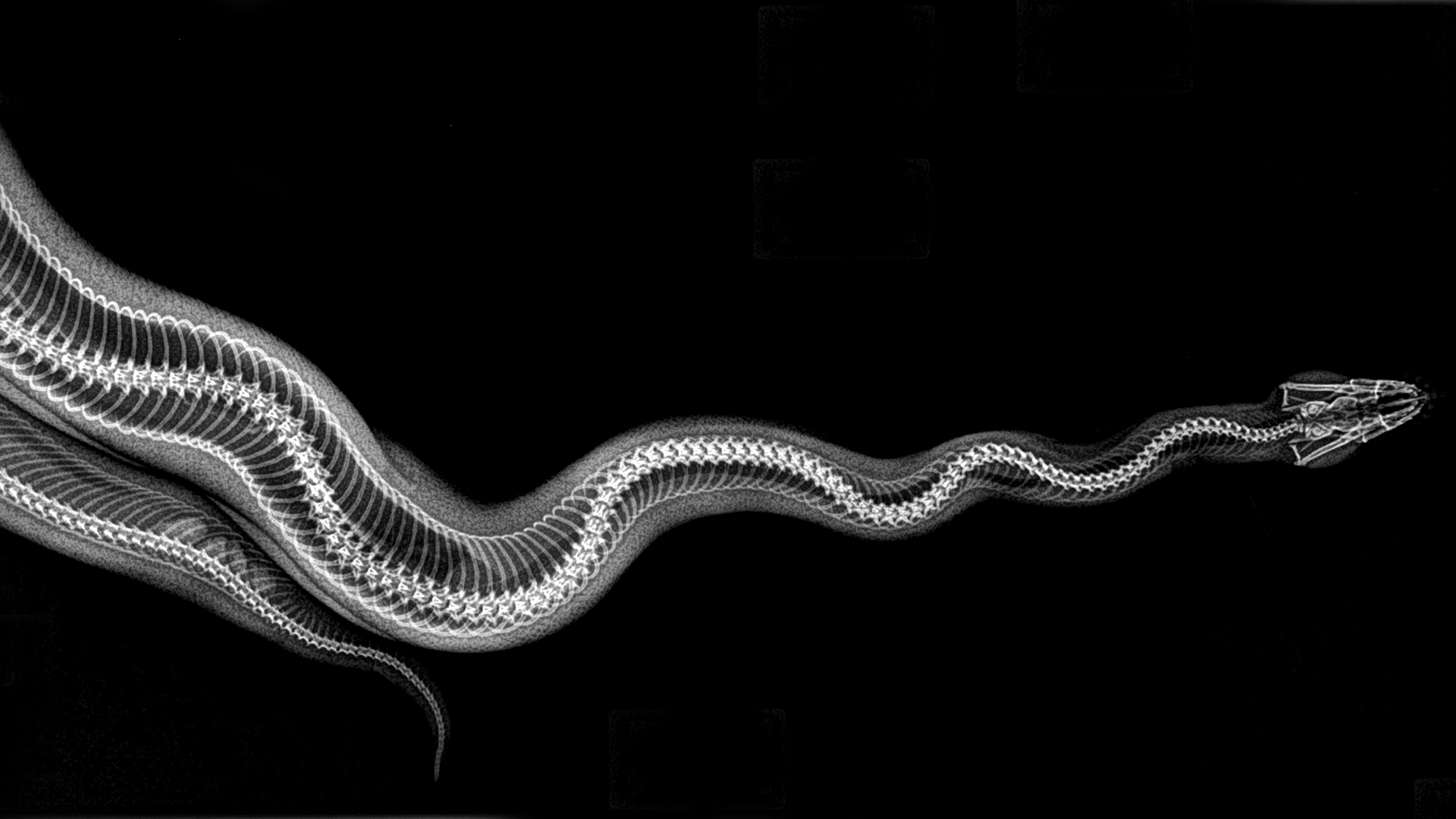

Ball python

For animals at the Oregon Zoo, X-rays are part of their annual checkup with the zoo veterinarian. The flexible spine inside a sinuous adult ball python can include around 200 vertebrae and 400 ribs.

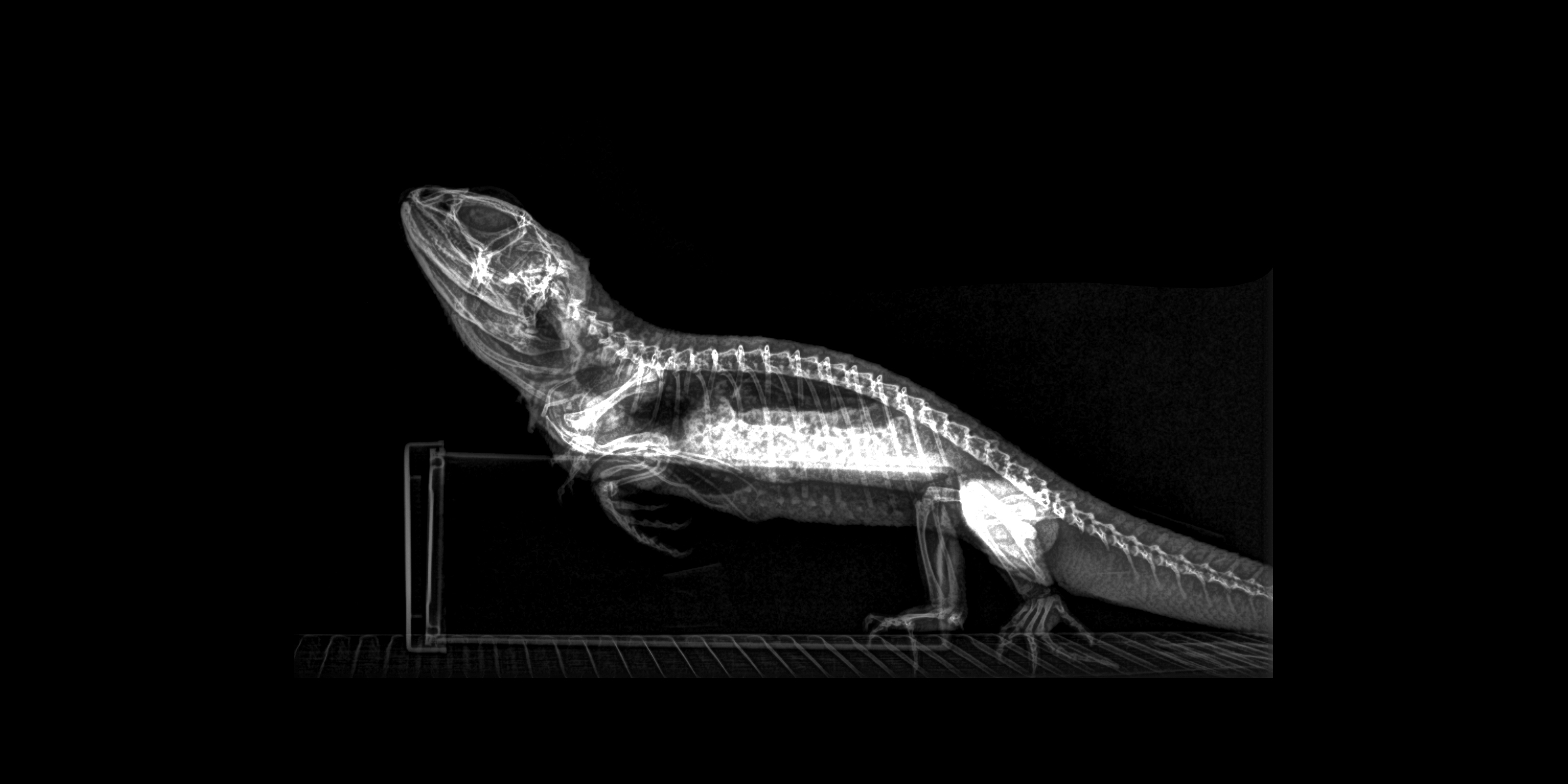

Bearded dragon

Digital X-rays help zookeepers monitor animal health. This bearded dragon has a normal skeleton, but lack of light and certain nutrients can lead to a thinning of bone density in these reptiles, a condition known as metabolic bone disease.

Bufflehead duck

Though it's hard to tell from its skeleton, bufflehead ducks have a fluffy covering of feathers that makes them look endearingly pudgy.

Cape porcupine

Do those pointy incisors look like the teeth of a fearsome carnivore? They're not. They belong to the Cape porcupine, an omnivorous mammal that is the largest rodent in Africa. These porcupines mostly dine on plants, though they are also known to eat carrion and gnaw on bones.

Dwarf mongoose

Though this X-ray appears to have captured a dwarf mongoose mid-leap, the anesthetized animal is merely lying on a table. Digital X-ray technology is faster than traditional X-ray techniques, enabling veterinarians to shorten the time that their X-ray subjects must spend under anesthesia.

Rodrigues flying fox

The Rodrigues flying fox is a type of large fruit bat native to the island of Rodrigues, east of Madagascar. Its fur, invisible in this X-ray, is typically chestnut brown, with a mantle of golden fur covering its shoulders, neck and head.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

American beaver

The wide, flat tail of a beaver is mostly fleshy padding, as this X-ray reveals.

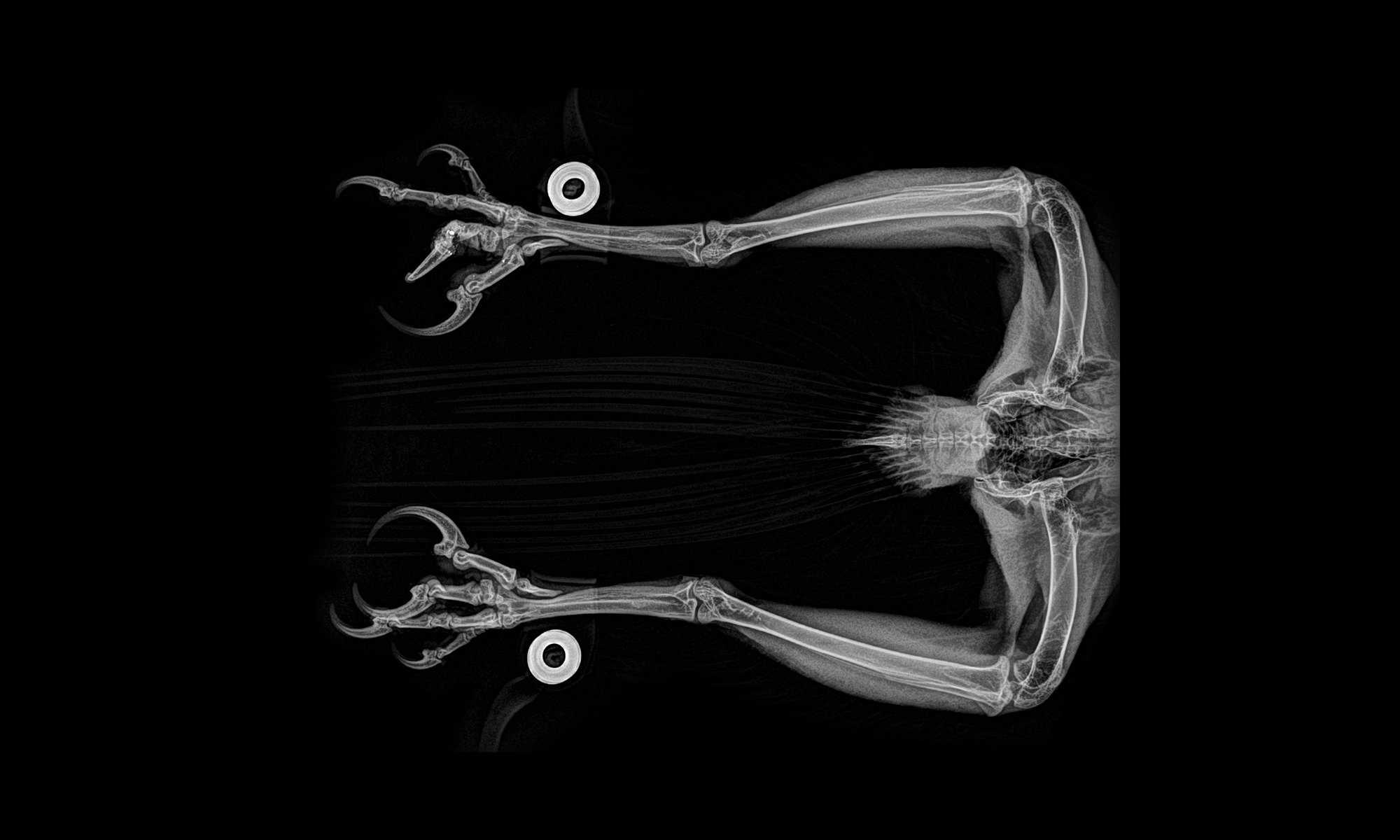

Golden eagle

While this view of a golden eagle's butt and legs isn't very dignified, it does highlight the impressive claws that this predatory bird uses to snatch its prey. While its feathers are invisible in the image, golden eagles are known for having long tail feathers that extend farther behind the bird than its head extends up front.

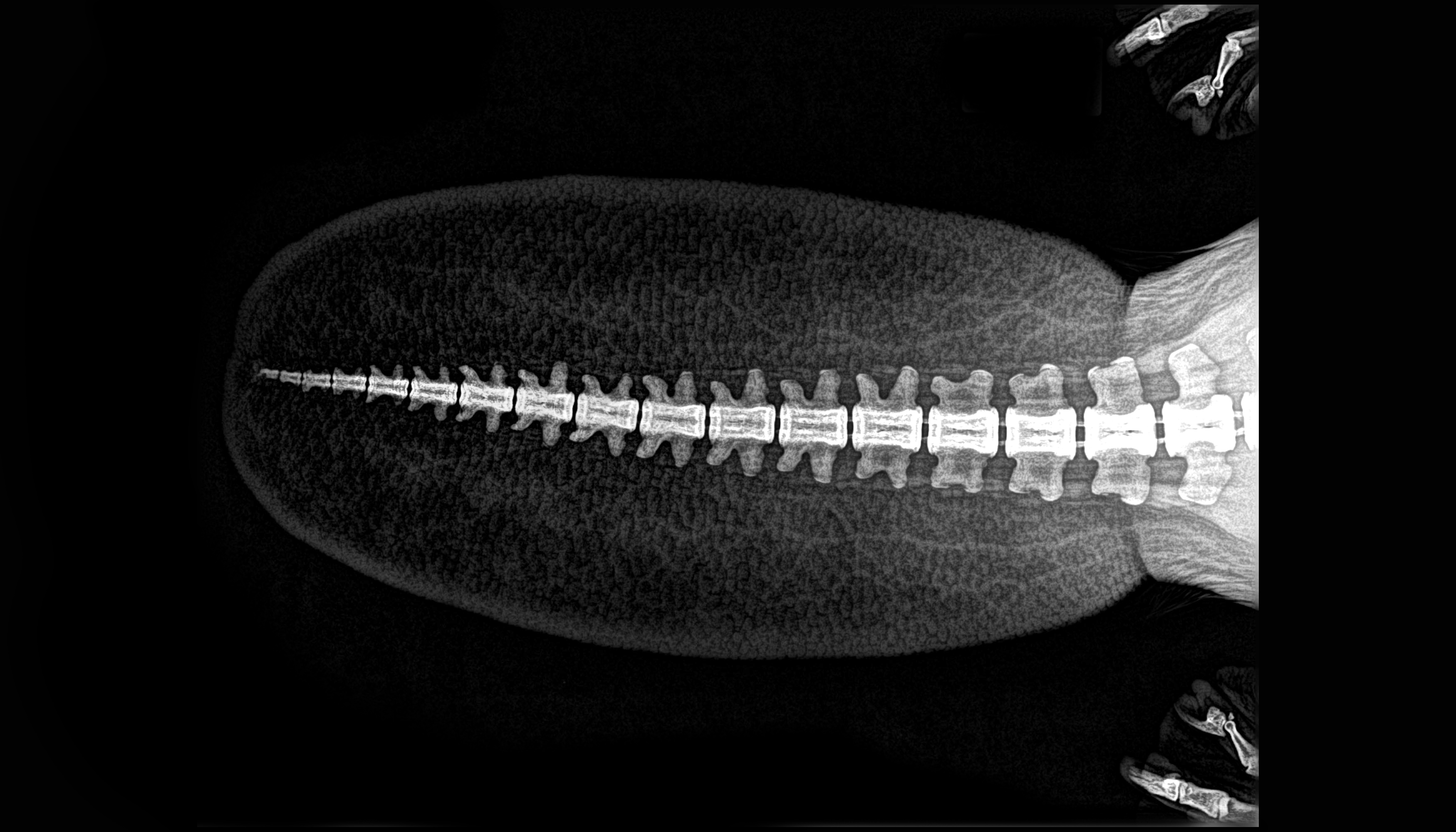

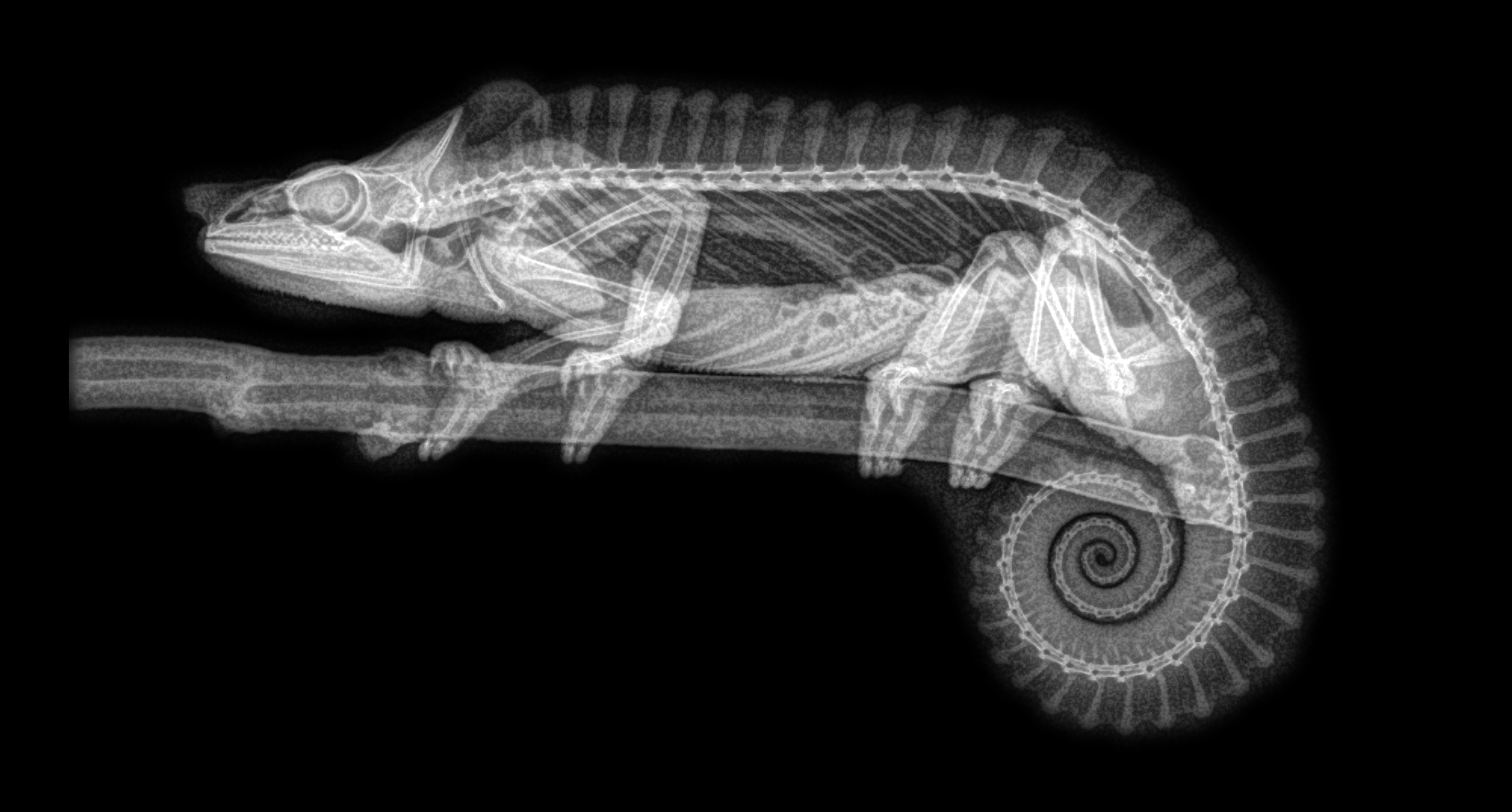

Meller' chameleon

One of this chameleon's most distinctive traits — a "horn" sticking out over its nose — is almost invisible in the X-ray. These large chameleons can grow up to 2 feet long (0.6 meters) and weigh over a pound (0.5 kilogram).

Amur tiger

"How do you X-ray a 320-pound Amur tiger? Very carefully, of course," representatives of the Oregon Zoo wrote in a blog post. Amur tigers were once common in the Korean Peninsula, northern China and eastern Russia, but today only about 540 individuals remain in the wild.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.