World's Oldest Animal Drawing, Discovered in Borneo Cave, Is a Weird Cow Beast

A 40,000-year-old painting of a mysterious, wild cow-like beast discovered in a Borneo cave is the oldest human-made drawing of an animal on record, a new study finds.

The discovery indicates that figurative cave art — one of the most significant innovations in human culture — didn't begin in Europe as many scientists thought, but rather in Southeast Asia during the last ice age, the researchers said.

Drawing animals, an accomplishment in itself, may have been a gateway for illustrating other aspects of the human experience, including hunting and dance. "Initially, humans made figurative painting of large animals and they later start depicting the human world," said study co-lead researcher Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist and geochemist at Griffith University in Australia. [In Photos: The World's Oldest Cave Art]

The ancient artwork covers the walls of secluded limestone caves in the rugged and remote mountains of the East Kalimantan province of Indonesian Borneo. Researchers have known about these human-made drawings since 1994, but they didn't know when the illustrations were created until now, said Aubert, who worked with Indonesia's National Research Centre for Archaeology (ARKENAS) and the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB).

The researchers collected calcium-carbonate samples from the Kalimantan cave drawings so they could do uranium-series dating — a technique made possible by radioactive decay. When rainwater seeps through limestone, it dissolves a small amount of uranium, Aubert told Live Science. As uranium (a radioactive element) decays, it turns into the element thorium. By studying the ratio of uranium to thorium in the calcium carbonate (limestone) that is coating the cave art, researchers determined how old the initial coating was, he said.

The oldest figurative art — the mystery animal that is likely a species of wild cattle that once stomped around the jungles of Borneo — was at least 40,000 years old, Aubert said. Previously, the oldest known animal painting in the world was an approximately 35,400-year-old babirusa, or "pig-deer," on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, he said.

Artwork through the ages

The team's results showed that the ancient artwork in East Kalimantan was made during three distinct periods. The first phase, which dates to between 52,000 and 40,000 years ago, includes hand stencils and reddish-orange ochre-drawn animals — mostly the banteng (Bos javanicus), a type of wild cattle that still lives in Borneo, and the mysterious, unknown wild cow, Aubert said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

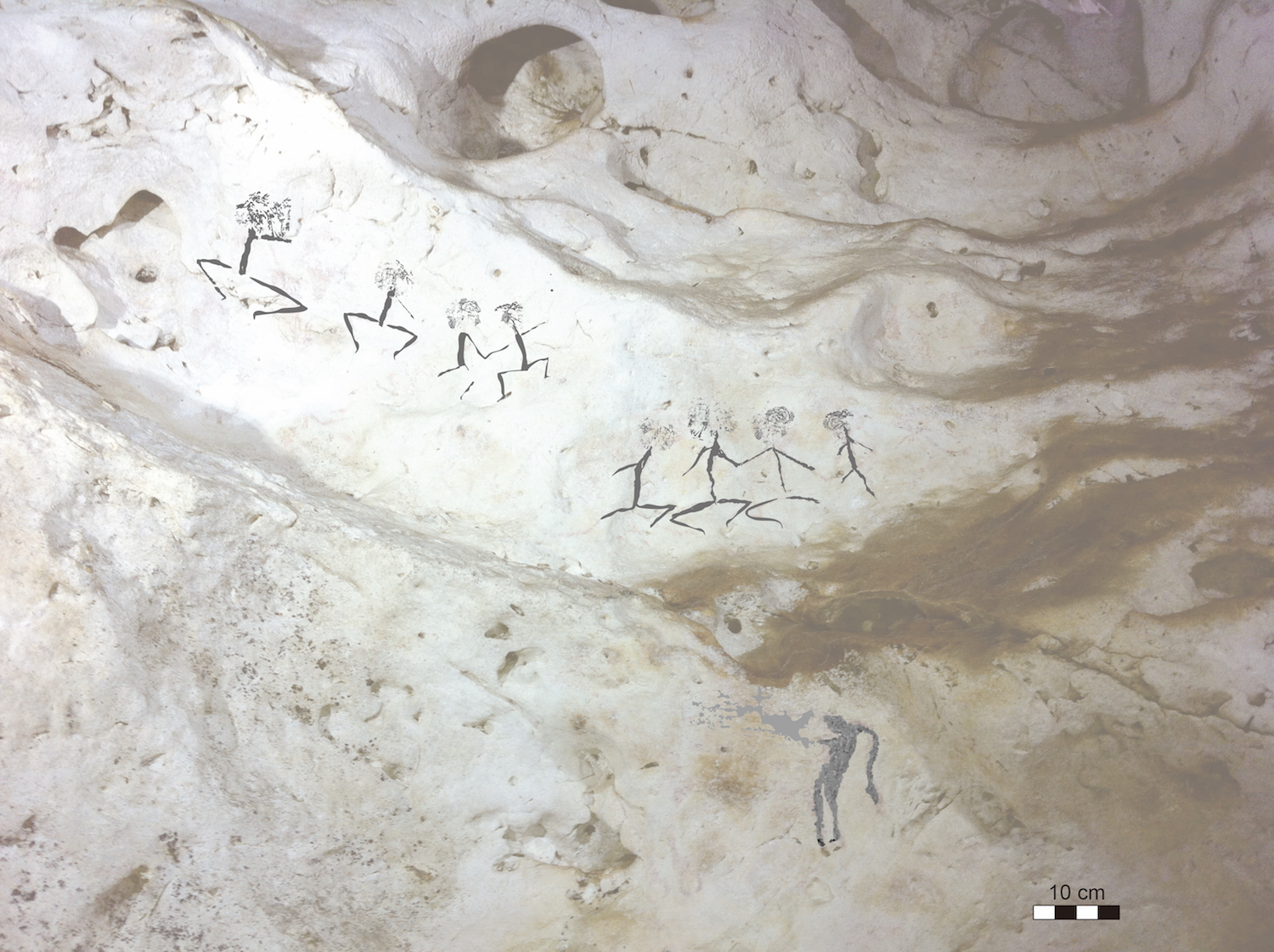

A major change happened to the culture during the icy Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago, which led to a new style of rock art — one that focused on the human world. The artists in this phase favored a dark mulberry-purple color and painted hand stencils, abstract signs and human-like figures wearing elaborate headdresses and engaging in various activities, such as hunting or ritualistic dancing, the researchers said.

"We don't know if these [different types of cave art] are from two different groups of humans, or if it represents the evolution of a particular culture," Aubert said. "We are planning archaeological excavation in those caves in order to find more information about these unknown artists."

The final phase of rock art includes humanlike figures, boats and geometric designs that were mostly drawn with black pigments, the researchers said. This type of art is found elsewhere in Indonesia and may come from Asian Neolithic farmers who moved into the region about 4,000 years ago, or more recently, the researchers said. [Photos: Oldest Known Drawing Was Made with a Red Crayon]

Location, location

During the last ice age, Borneo (Earth's third-largest island) sat on the easternmost edge of Eurasia.

"It now seems that two early cave art provinces arose at a similar time in remote corners of Paleolithic Eurasia: one in Europe, and one in Indonesia at the opposite end of this ice age world," study co-researcher Adam Brumm, an associate professor of archaeology at Griffith University, said in a statement.

It's possible that rock art spread from Eurasia to Sulawesi, where the babirusa drawing resides, before colonizing humans spread it farther to places like Australia, Aubert said.

The new finding shows further evidence that "the earliest art consisted of large animals painted in a remarkably naturalistic style, with emphasis on the musculature and form of the animal's body," said Susan O'Connor, a professor of archaeology at the College of Asia & the Pacific at Australian National University, who wasn't involved with the research.

"The location of these ancient paintings of animals and hand stencils perhaps marks the passage of the first modern humans as they moved through mainland Asia and out into the islands of Wallacea, lying between the mainland and continental Sahul (Australia and New Guinea which were joined at this time)," O'Connor told Live Science in an email. "They may have used art to mark and 'humanize' these new and unfamiliar landscapes."

The newly dated cave art fits in with the emerging picture of early humans. Homo sapiens left Africa between about 70,000 and 60,000 years ago, and "once they spread out across Eurasia, they developed, after about 40,000 years ago, the desire (or ability) to produce figurative art," Christopher Henshilwood, director of the Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour at the University of Bergen in Norway, who wasn't involved with the study, told Live Science in an email. "This find in Indonesia thus adds to our knowledge regarding the evolution of figurative art, perhaps first in Asia, then in Europe and Africa." (Africa's oldest figurative art dates to about 30,000 years ago at the Apollo 11 Cave in Namibia, Henshilwood noted.)

The study was published online today (Nov. 7) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.