Antarctica: The Ice-Covered Bottom of the World (Photos)

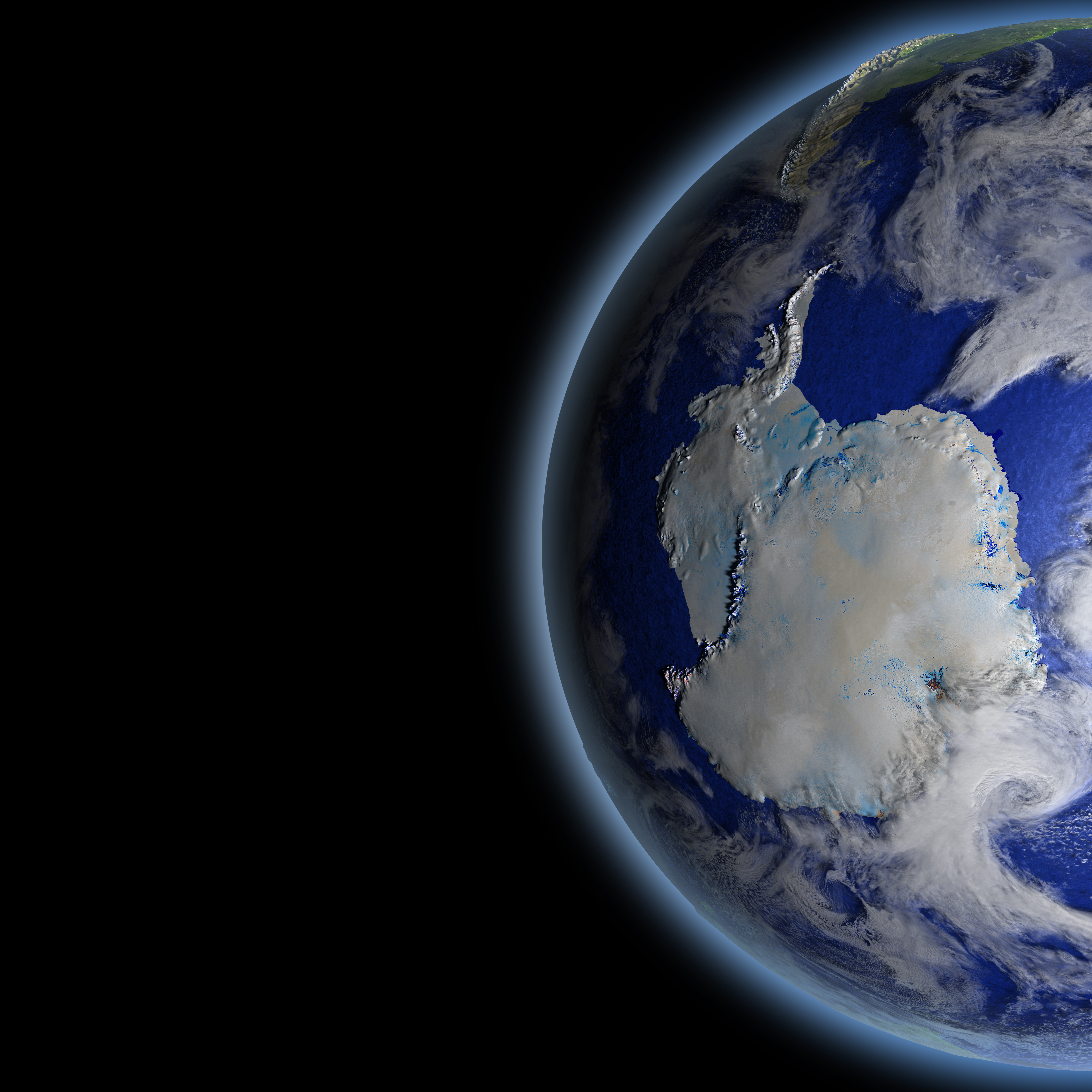

Amazing Antarctica

Antarctica is a place of extremes. It's the southernmost continent and hosts the coldest temperature ever directly recorded on Earth's surface — a bone-chilling minus 128.6 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 89.2 degrees Celsius) logged at Russia's Vostok research station. It's also home to the windiest spot on the planet — Mawson station, where max winds have been clocked whipping at 154 mph (248.4 km/h), according to CoolAntarctica. Here's a look at the awe-inspiring ice cake at the bottom of our planet…

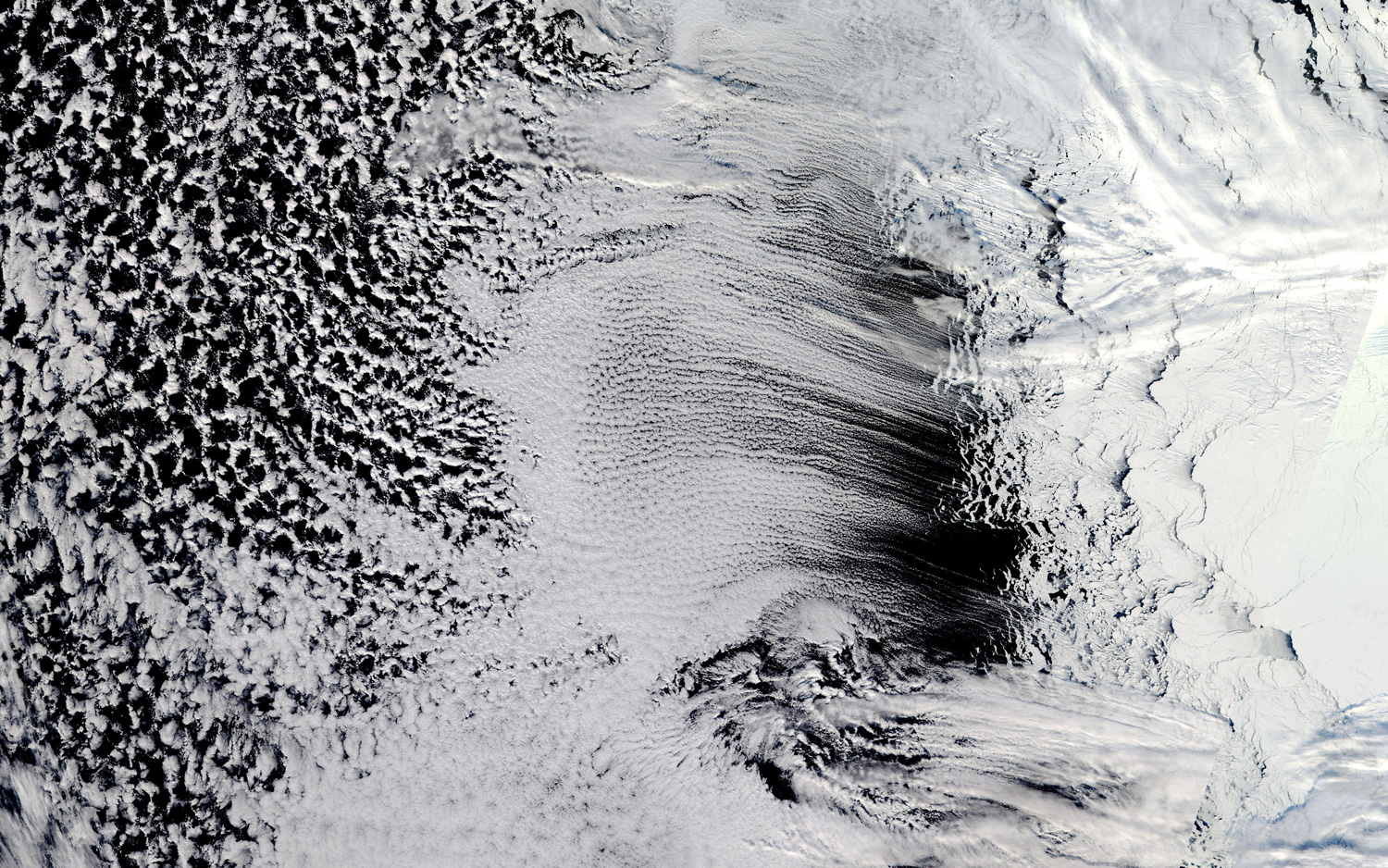

Cloud streets

Long, parallel bands of cumulus clouds (called cloud streets) stretch over the Amundsen Sea off West Antarctica in this image captured from space on Sept. 12, 2018. The puffy sky streaks likely formed as cool air blowing from Antarctica and the sea ice hit warmer open waters, picking up heat and rising into the atmosphere. There, these so-called thermals would have bumped into a layer of warm air, a lid of sorts, causing "the rising thermals to roll over and loop back on themselves," according to NASA. On the upper side of these "cylinders of rotating air," NASA said, clouds form.

On the move

Don't be fooled, Antarctica is not a still, ever-silent place. It's constantly on the move, with glaciers inching toward the sea, ice blocks breaking off their land-leashed parent shelves and the resulting icebergs splintering into their own smaller chunks of floating ice. Some icebergs look like carefully cut rectangles, like the ones shown here in this aerial view captured in 1997. They're called tabular icebergs.

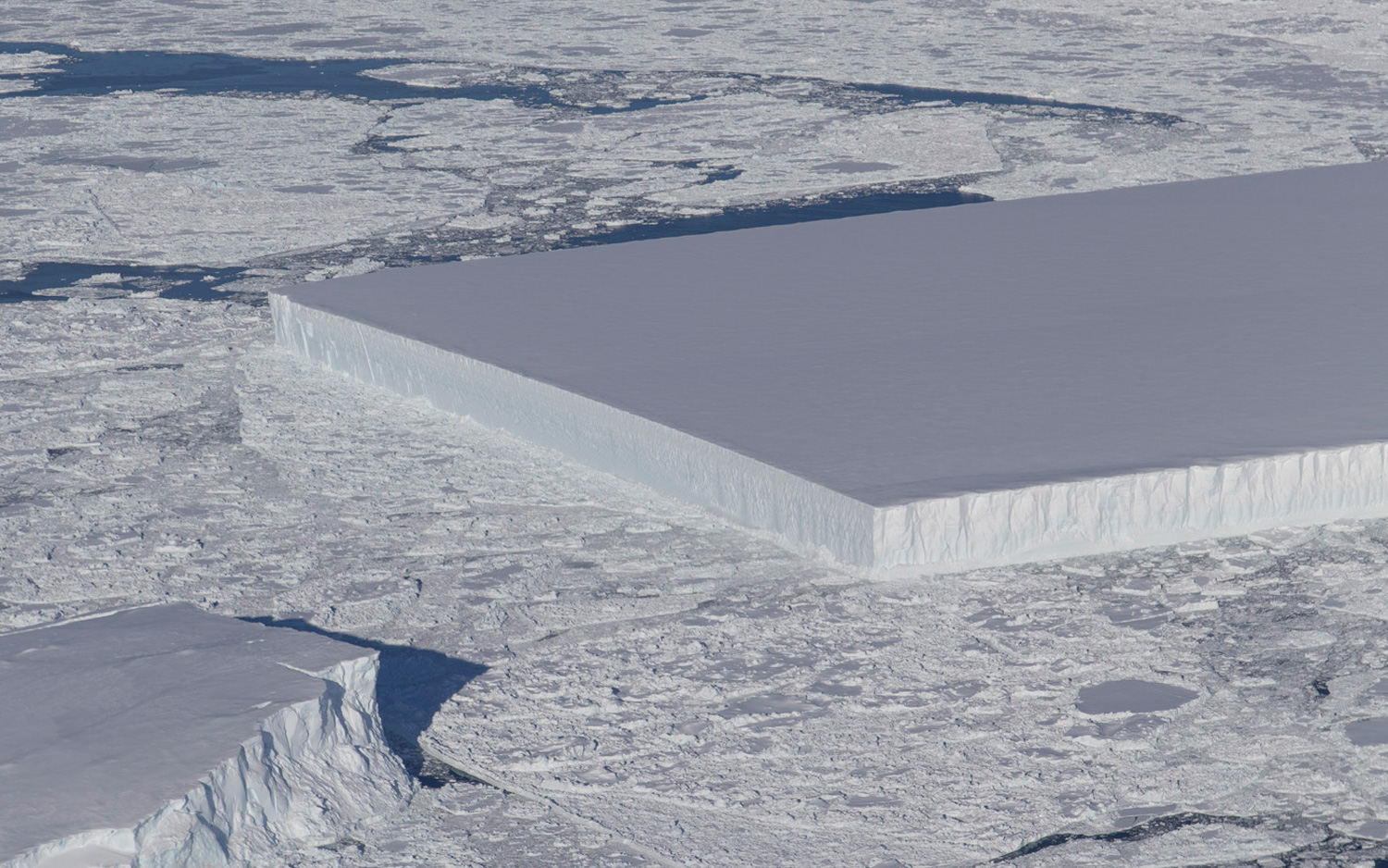

Clean break

On Oct. 16, 2018, during a research flight above the Antarctic Peninsula, Jeremy Harbeck, from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, snapped a photo showing "an unusually angular iceberg floating amid sea ice just off the Larsen C ice shelf," according to NASA. And it's relatively big, about 3,000 feet (900 meters) wide and 5,000 feet (1,500 m) long. The trapezoidal slab could be the result of an enormous iceberg called A-68A slamming into an immovable ice rise, resulting in the splintering of such neatly cut squares and rectangles, according to NASA.

Volcanic beauty

Resting quietly in the Indian Ocean, Amsterdam Island is a small bit of land about 21 square miles (55 square kilometers) in size and considered part of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands. It was formed by a now-extinct volcano that reaches an altitude of nearly 3,000 feet (911 meters); the island formed between 400,000 and 200,000 years ago, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

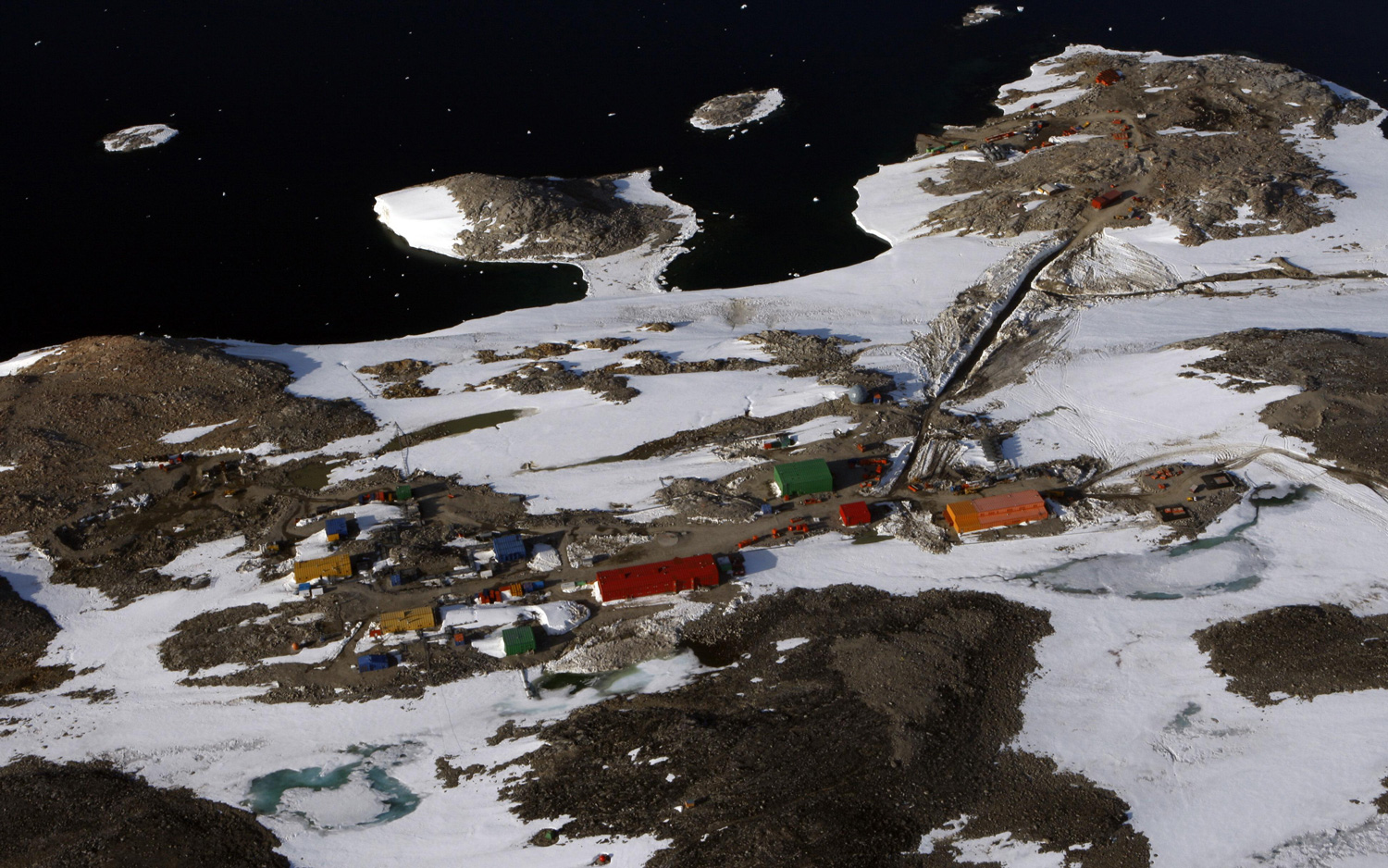

Permanent base

This permanent Antarctic research station, called Comandante Ferraz base, is named after Brazilian Navy Commander Luís Antônio de Carvalho Ferraz. The aerial view was captured March 10, 2014.

Artists's palette

Some aerial shots of the Antarctic look more impressionist art than real-life phenomena. Here, the sunset paints ice floes around Antarctica in pastel shades of pink and orange.

Bergy bits

Icebergs rise from the sea surface in this aerial view of Antarctica, captured in 1997. The term iceberg refers to ice chunks that are bigger than 16 feet (5 meters) across, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. As for wee icebergs, smaller than the official threshold, scientists apparently call those bergy bits and growlers, NSIDC said.

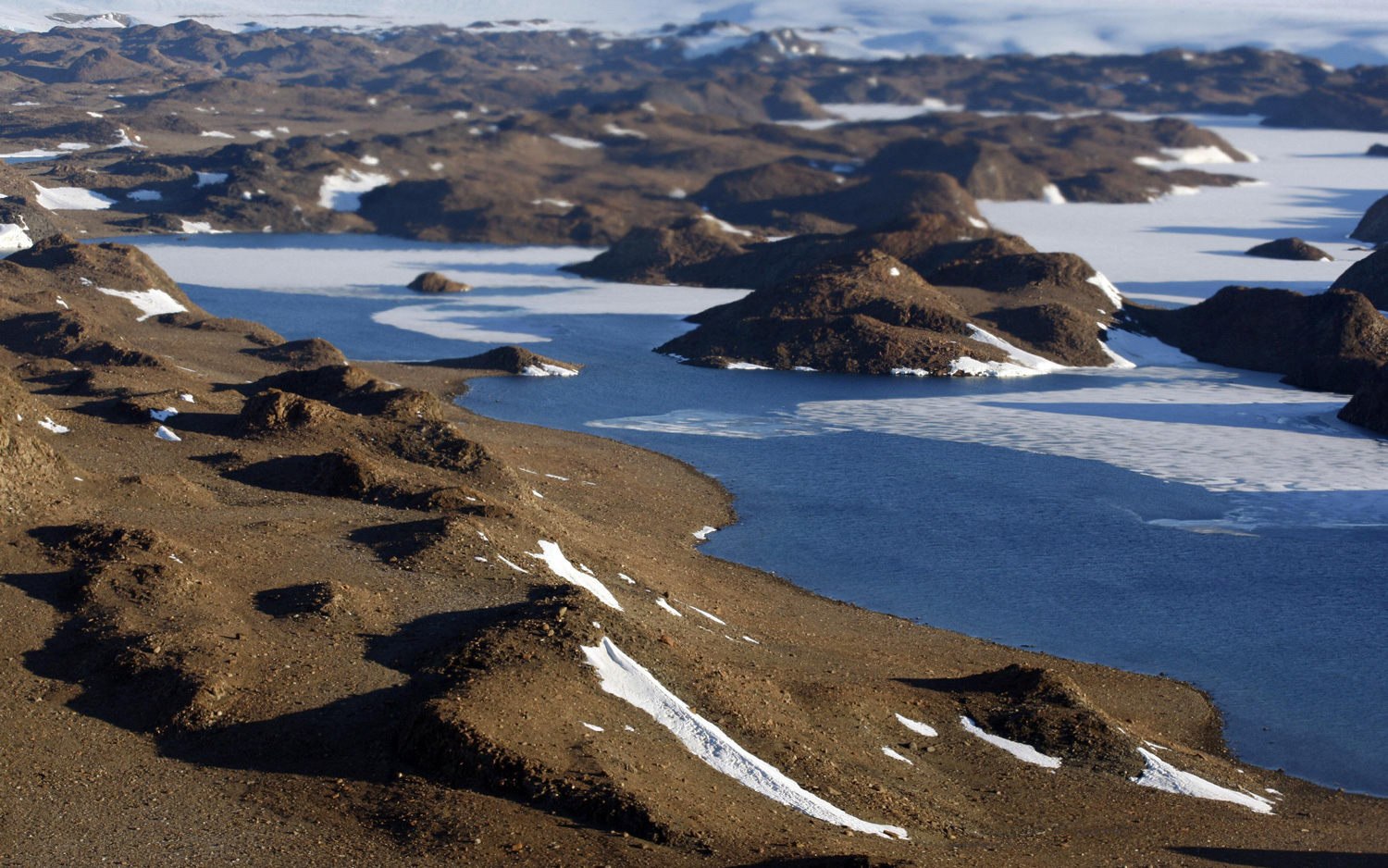

Bunger Hills

Antarctic landscapes aren't all white and frosty blue. Take Bunger Hills, seen in this aerial view captured in January 2008. This snow- and ice-free terrain was discovered in February 1947 by a pilot who was part of the U.S. Navy's Operation Highjump. At the time, the 390-square-mile (1,000 square kilometers) spot was considered an "oasis," according to a paper by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) published in 1988. Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who led Operation Highjump, described it as "a land of blue and green lakes and brown hills in an otherwise limitless expanse of ice," according to the USGS paper.

Casey Station

Casey Station is one of three permanent stations run by the Australian Antarctic Division. Named in honor of the then Governor-General of Australia Richard Casey, the station was opened on Feb. 19, 1969, as a replacement to the Wilkes station, which was buried by deep snowdrifts, according to the Australian Antarctic Division. The station is located in the Windmill Islands, just outside the Antarctic Circle.

Glacial texture

The southernmost continent is bathed in sunlight during the Southern Hemisphere summer (while its northern cousin is shrouded in darkness). Here, in an image captured by a NASA satellite on Dec. 13, 2010, along the Princess Ragnhild Coast in East Antarctica, icebergs pop out due to the low-angle sunlight. The rougher-textured icebergs likely split from the coast, bobbing in the open ocean before ending up here, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. Scars from all that jostling roughed up the ice surfaces. The icebergs with smoother surfaces were birthed locally, not having been ravaged by the seas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.