Warmer, Wetter Than Usual Winter Headed for Much of US

Just over half of the United States has no need to fear an exceptionally frigid, frozen winter in the coming months — instead, they'll likely experience a warmer and wetter winter than usual, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center.

In the three coming months — December, January and February — the West Coast, the Mountain states and chunks of the Midwest and Northeast (although not New York or Boston) are all forecast to have above-normal temperatures for the season, as well as increased precipitation (meaning rain and snow), the Climate Prediction Center announced at a news conference yesterday (Nov. 15).

The warm and wet winter is due, in part, to weather patterns such as El Niño and decadal changes in ocean patterns , as well as climate change, said Stephen Baxter, a meteorologist and seasonal forecaster at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center. [Winter Wonderland: Images of Stunning Snowy Landscapes]

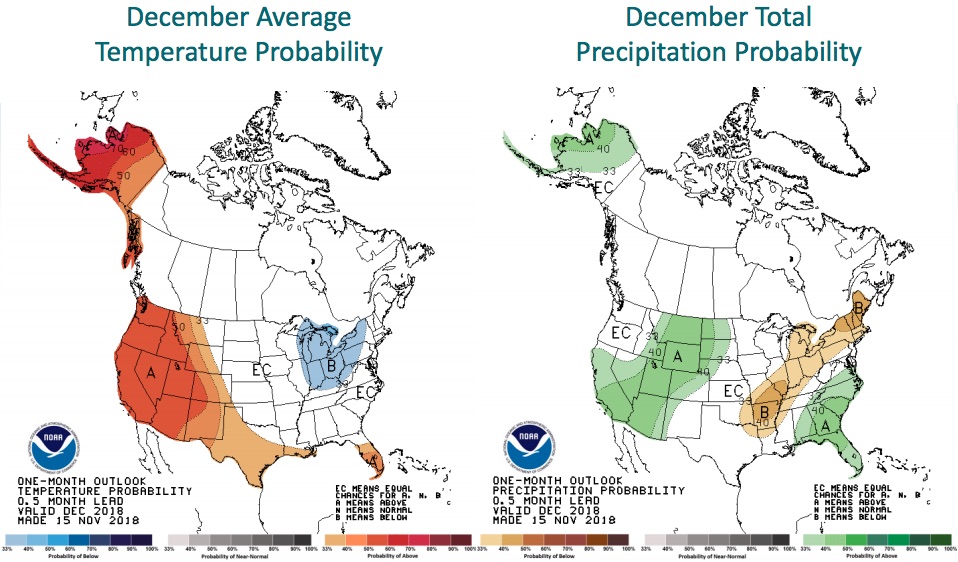

During the news conference, Baxter first presented the weather outlook for December, which is shown below. Areas that are red, orange and yellow are predicted to have above-normal winter temperatures, he said. The blue region covering the Great Lakes region is expected to be cooler than usual. Meanwhile, the white-colored areas in the United States are expected to have typical winter temperatures.

As for December precipitation (the map on the right), the green swaths over parts of California, the Mountain states and the Southeast indicate above-normal rainfall, while the yellow patches going diagonally from Texas to Maine show that those regions will likely receive less precipitation than average.

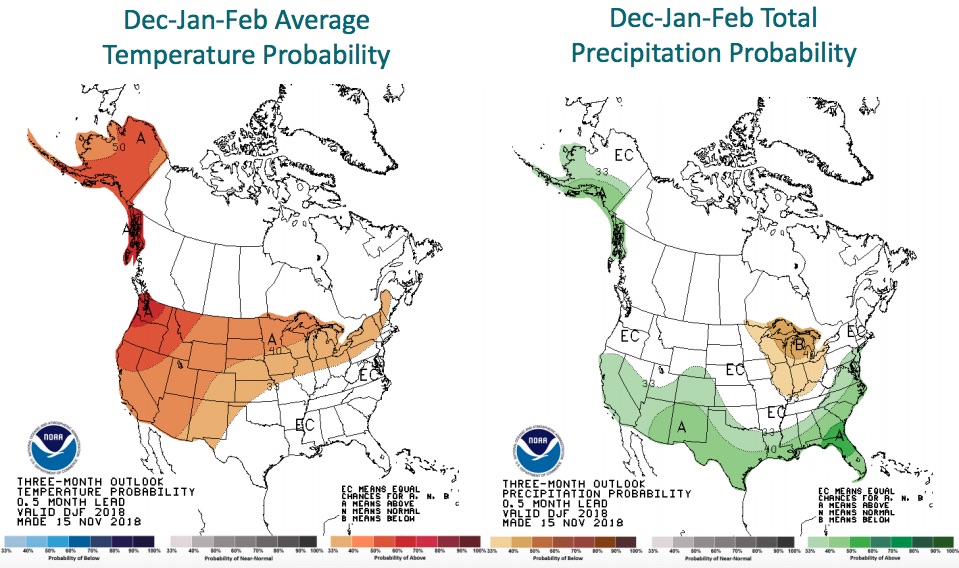

The December-January-February temperature outlook is slightly different. Notice how — in the map shown below — the above-average temperatures still cover Alaska and much of the American West and Midwest, but that the predicted cold spot over the Great Lakes area disappears.

The three-month precipitation outlook shows a different story. It's predicted that the lower tier of the United States will get more than the average precipitation, while parts of the Midwest and the Great Lakes regions will get below-normal precipitation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It appears that El Niño is partly responsible for the warmer temperatures on the West Coast. El Niño happens when the equatorial Pacific Ocean warms, which in turn sloshes warm water and humid air east toward the Americas. El Niño also tends to lead to the easternly extension of the jetstream from southeast of Japan to across the Pacific Basin, and to a low-pressure system in the northeast Pacific, Baxter said.

All of these factors tend to "lead to anomalous warm air convection in western United States and southern Alaska," Baxter said. (In another words, you have warm air where you normally wouldn't.) "And so you tend to have less cold air intrusions there. You also tend to have more storm activity across the southern tier of the U.S., and so that is that increased stormtrack there."

Climate change is also playing a role in this winter's weather, although it can be difficult to suss just how much, Baxter said. That's because so many factors influence the weather, such as increased greenhouse gas emissions and decadal changes in ocean patterns , and so it can be challenging to determine which signals are coming from where.

"Part of the challenge is just disentangling these things," Baxter said. "Climate now is higher than the fixed 30-year base period that we've used … and a good portion of that is long-term climate change."

Instead of taking the average of the past 30 years, climatologists are finding they can get a more accurate picture of the current climate by taking an average of just the past 15 years. And, according to NOAA and NASA, the five warmest years on record happened in the 2010s, while the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998, Climate Central reported earlier this year.

- Images: Amazing Shots of Storms Light Up Weather Photo Contest

- In Photos: Frozen Lakes in Winter

- In Photos: Best National Parks to Visit During Winter

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.