These Ancient Termite Mounds Are As Old As the Egyptian Pyramids. And They're Visible from Space.

The roughly 4,000-year-old termite mounds — there are about 200 million of them — are so immense that each has nearly 1,800 cubic feet (50 cubic meters) of soil in it. Taken together, these termites have excavated more than 2.4 cubic miles (10 cubic kilometers) of earth, which is equivalent to the volume of about 4,000 Great Pyramids of Giza, the researchers said.

In other words, this is the "greatest known example of ecosystem engineering by a single insect species," the researchers wrote in the study. [In Photos: Mima Mounds Around the World]

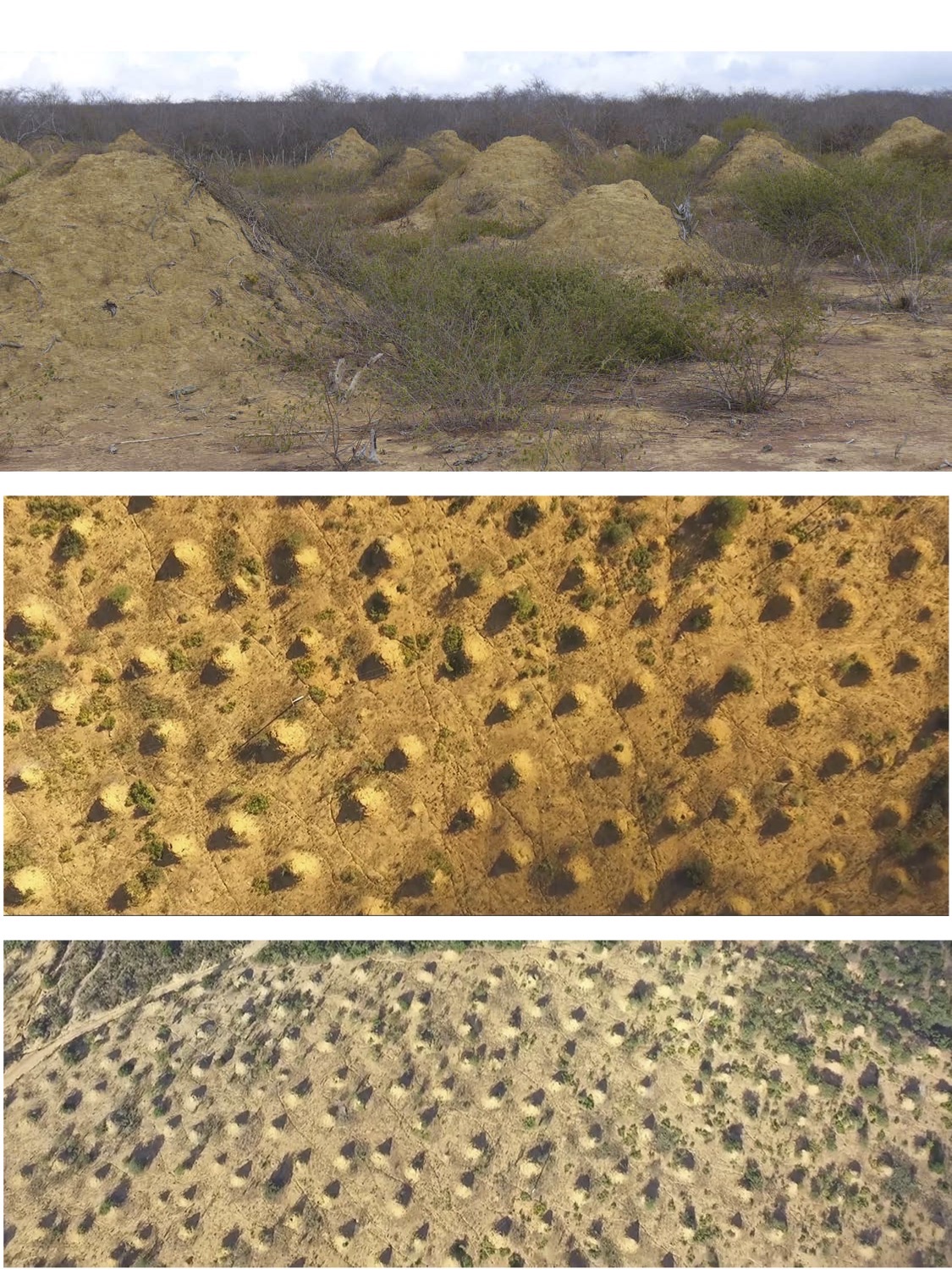

The termite-crafted mounds in northeastern Brazil span an area about the size of Great Britain, the researchers said. But these mounds — measuring about 8 feet (2.5 meters) tall, with a diameter of about 30 feet (9 m) — aren't nests, the researchers said. Over thousands of years, termites (Syntermes dirus) excavated dirt as they made an extensive, interconnected tunnel system underground. Then, they dumped the dug-up soil aboveground, leading to the mounds.

"These mounds were formed by a single termite species that excavated a massive network of tunnels to allow them to access dead leaves to eat safely and directly from the forest floor," Stephen Martin, the chair of social entomology at the University of Salford in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

The mounds were hidden by Brazil's thorny-scrub caatinga forests, a semiarid landscape covered by deciduous trees for years. Members of the public, including scientists, began to discover them only over the past few decades as the land was cleared for pasture.

To learn more about the mounds, the scientists collected soil samples from the centers of 11 of them. The results showed that the mounds were filled between 3,820 and 690 years ago, making them about the same age as the world's oldest-known termite mounds in Africa.

The researchers also investigated the mounds' spacing, which resembles the "mima mounds" of Washington state — mysterious lumps that may have been made by plants, although some scientists think that gophers are the culprits. The termites' mounds also resemble South African "heuweltjies" and Namibian fairy circles, the researchers noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists have debated for years about how all of these mysterious mounds formed. In this case, it didn't appear that aggression between local termites of neighboring mounds explained the mounds' spacing. Rather, it's possible that the termites arranged the mounds based on the way the interconnected tunnels ran beneath them, as well as how the leaves they ate episodically fell in the forest, the researchers said.

Given the tunnels system's complexity, it's likely that a pheromone map helps guide the termites through the underground maze, the researchers said. The giant network also gives the termites a safe route to a sporadic food supply, a similarity also seen in naked mole rat tunnels, the researchers said.

"It's incredible that, in this day and age, you can find an 'unknown' biological wonder of this sheer size and age still existing, with the occupants still present," Martin said.

He added that the mounds are just a mass of excavated soil, meaning they don't have any internal structure.

The study was published online yesterday (Nov. 19) in the journal Current Biology.

- Photos: Ancient Ants & Termites Locked in Amber

- In Photos: Looking Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza

- Photos: The Amazing Pyramids of Teotihuacan

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.