MDMA Makes People More Cooperative... But That Doesn't Mean More Trusting

The club drug MDMA — also called ecstasy or molly — is often said to increase feelings of emotional closeness to others and empathy. Now, a new study from England suggests that the drug really does have an effect on how people feel and act toward others.

In the study, the researchers found that MDMA made people more cooperative, but only with those who were deemed trustworthy.

In other words, MDMA doesn't make people natively trusting of others, the researchers said.

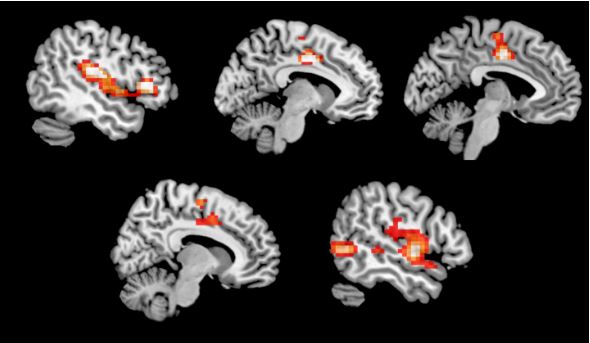

The study also found that taking MDMA led to increased brain activity in areas of the brain thought to be involved in social interaction and the understanding of other people's thoughts and intentions. [6 Party Drugs That May Have Health Benefits]

And because MDMA is also being studied as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the new findings are "an important and timely step" leading to a better understanding of the social and emotional effects of the drug, the researchers wrote in their paper, published Nov. 19 in The Journal of Neuroscience.

Cooperate or compete

MDMA, which is illegal in the United States, is known to increase the activity of chemical messengers in the brain linked to behavior and mood, including dopamine and serotonin. But little is known about how different chemical messaging systems in the brain contribute to complex social behavior, such as cooperation, the researchers said.

The new study involved 20 healthy men in their 20s and 30s who did not have psychiatric or substance-use disorders, but who had taken MDMA at least once before.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The participants were randomly assigned to receive either 100 milligrams of pure MDMA (the chemical 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) or a placebo before playing a game while they had their brain scanned. In the game, called the Prisoner's Dilemma, participants choose to either compete or cooperate with another player. If both players choose to cooperate, they both get points. But if one player chooses to cooperate and the other choses to compete, the one who chose to compete gets all the points.

The participants were told they were playing against actual people, but in reality, they were playing against a computer with preprogrammed responses. The researchers programmed the computer player to be either "trustworthy," meaning it cooperated in most games, or "untrustworthy," meaning it competed in most games.

The study found that participants who took MDMA were more likely to cooperate with trustworthy players, compared with participants who took a placebo. But MDMA did not have an effect on their cooperation with untrustworthy players — both those on MDMA and the placebo cooperated with untrustworthy players at the same rate.

"MDMA did not cause participants to cooperate with untrustworthy players any more than normal," senior study author Mitul Mehta, a professor of neuroimaging and psychopharmacologyat King's College London, said in a statement.

In addition, the study found that when participants were "betrayed" — that is, when they chose to cooperate but their opponent chose to compete — it reduced their tendency to cooperate during the next game. But, those who took MDMA recovered cooperative behavior with trustworthy players faster, compared with those who took a placebo.

"This tendency to rebuild a relationship led to higher overall levels of cooperation with trustworthy partners," said lead study author Anthony Gabay, a neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, who conducted the work while at King's College London.

MDMA also increased activity in the brain areas known as the superior temporal cortex and midcingulate cortex. Both of these areas are thought to be important in understanding the thoughts, beliefs and intentions of others.

The findings may have implications for a number of psychiatric conditions that involve problems with "social cognition," or the understanding of thoughts and emotions of others. Such conditions include depression and schizophrenia.

"Understanding the brain activity underlying social behavior could help identify what goes wrong in [these] psychiatric conditions," Mehta said.

The researchers noted that because the study involved only men, it's unclear if the findings also apply to women.

- 9 Weird Ways You Can Test Positive for Drugs

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain

- 7 Ways Marijuana May Affect the Brain

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.