Mom's Phone Call Helps Uncover Oldest Long-Necked Dinosaur on Record

Thanks to a phone call from a scientist's mom, paleontologists have uncovered the oldest long-necked sauropod dinosaur on record.

The tale began in 2012, when Estefânia Temp Müller called her son, Rodrigo Temp Müller, a paleontologist in Brazil. Estefânia told her son that his uncle had found some fossils on a rural property in Agudo, in southern Brazil.

This motherly tip soon led to a major find: the discovery of the fossilized skeletons of a previously unknown sauropodomorph dinosaur, two of which had completely preserved skulls, Müller told Live Science. It's exceedingly rare to find the fragile skulls of sauropodomorph dinosaurs, especially early ones dating to the Triassic period, about 225 million years ago. [Photos: See the Armored Dinosaur Named for Zuul from 'Ghostbusters']

In all, the fieldwork to extract the fossils in a single block took nearly a month — the resulting rocky block weighed 5 tons (4.5 metric tons).

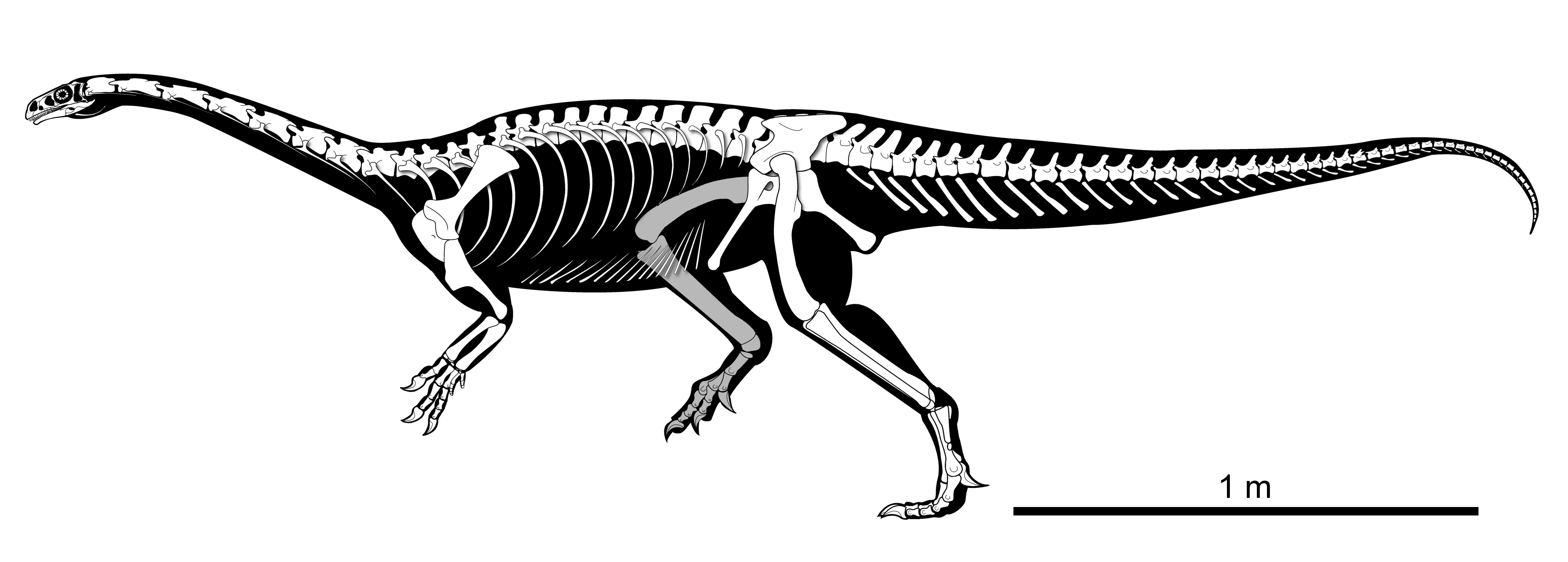

An analysis of the dinosaurs' bones revealed that this beast — dubbed Macrocollum itaquii — is the oldest sauropodomorph with an elongated neck on record. In other words, it appears that sauropodomorph dinosaurs developed their famously long necks, which gave them the ability to chow down on towering vegetation, during the early Norian, an age within the Triassic.

But what exactly do the researchers mean by "long neck?” It turns out, there is a specific definition.

"We can consider it a long neck when it is approximately as long as the trunk region," said Müller, the study's lead researcher and a paleontologist at the Center for Paleontological Research of the Fourth Colony at the Federal University of Santa Maria. "The neck of the new dinosaur is proportionally two times longer than the neck of previous sauropodomorphs, such as Buriolestes schultzi and Eoraptor lunensis."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, the extreme elongation found in the neck vertebrae of the newfound M. itaquii is usually seen in Massospondylus, a genus of sauropodomorph found in younger rocks from the early Jurassic period, Müller said.

The name Macrocollum itaquii combines the Greek word "makro" and the Latin word "collum," to showcase the dinosaur's elongated neck. The species name honors José Jerundino Machado Itaqui, who helped found the Center for Paleontological Research of the Fourth Colony.

M. itaquii was about 11 feet (3.5 meters) long and weighed about 220 lbs. (100 kilograms). However, the individuals the paleontologists found weren't quite fully grown, indicating that the adults were likely a bit larger, Müller said. What's more, even though later sauropods walked on all fours, these sauropodomorphs were bipedal, meaning they walked on just two legs.

"It had a small head and a long neck," Müller said. "In its hand, there was a large and sharp claw on its 'thumb.'" The shape of its teeth suggest that the dinosaur was a plant-eater, but it may have supplemented its diet with meat, he added.

The researchers even created a new group of dinosaurs — named Unaysauridae — that is made up of species from both Brazil and India, which were once connected in the supercontinent Gondwana. "This group helps [us] to understand the distribution of sauropodomorphs along the Triassic, indicating that they expanded from [the] western to [the] eastern [part of the] supercontinent of Gondwana, posteriorly reaching Laurasia [current-day North America and Eurasia]," Müller said. [Photos: Spiky-Headed Dinosaur Found in Utah, But It Has Asian Roots]

The discovery of M. itaquii is a boon to paleontology, as near-complete skeletons and fossilized skulls of sauropodomorphs are "really rare," said Stephen Poropat, a postdoctoral researcher of palaeontology at the Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, who was not involved with the study.

"I remember seeing a photo of the skull now named Macrocollum a few years ago and being blown away by how well-preserved it was," Poropat told Live Science in an email. "That such an ancient, [early] sauropodomorph had such a long neck is interesting, since it suggests that Macrocollum and its kin were already experimenting with the sorts of adaptations that were evidently put to such good use by their Jurassic and Cretaceous successors, the sauropods, for more than a hundred million years."

In the study, Müller and his colleagues speculate that because the fossils of the three M. itaquii individuals were found together, it's possible that these dinosaurs had gregarious behavior, meaning they may have lived in groups. But Poropat said that other factors might be at play.

"Although this might be true, it is also possible that several Macrocollum individuals died in the same small area for a different reason," Poropat said. "Perhaps they were clustered around a rapidly drying water hole or became mired in a bog or swamp independently of each other, but within a relatively short period of time."

If the researchers decide to strengthen the case for friendly behavior, they could do a detailed geological study of the site to determine the palaeoenvironment, Poropat said.

The study was published online today (Nov. 21) in the journal Biology Letters.

- Titanosaur Photos: Meet the Largest Dinosaur on Record

- Photos: See the 1st Dinosaur Bones Ever Found in Alaska's Denali National Park

- Photos: Unearthing Dinosauromorphs, the Ancestors of Dinosaurs

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.