What Are Amphetamines?

Amphetamines are central nervous system (CNS) stimulants, also called psycho-stimulants, that are often used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD and ADHD), narcolepsy, Parkinson's disease and obesity, according to the Center for Substance Abuse Research (CESAR) at the University of Maryland. Because of their high potential for abuse, the substances are also classified as Schedule II drugs by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

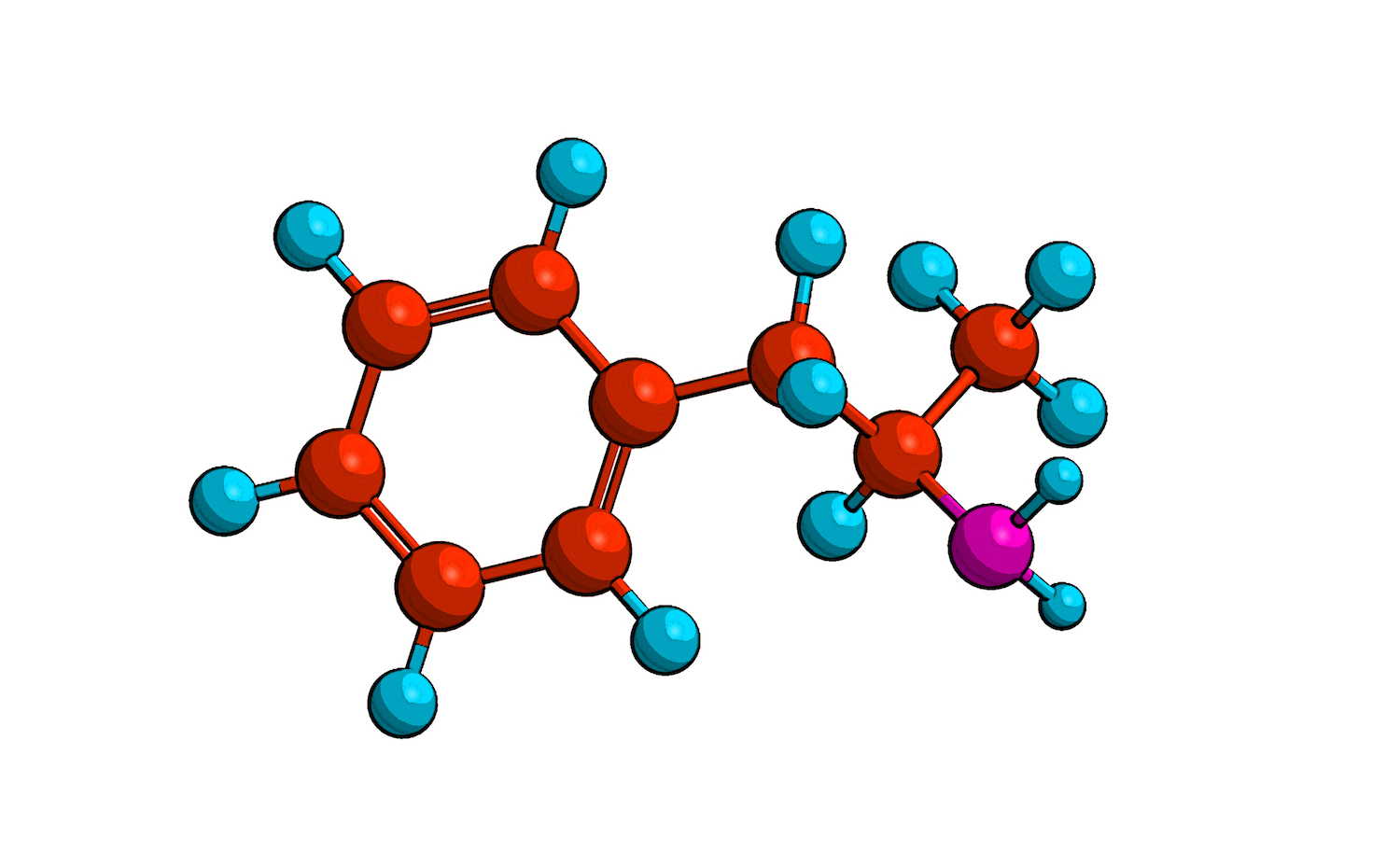

Amphetamines are derived from ephedra (Ephedra sinica), a plant native to China and Mongolia. For centuries, many cultures have used ephedra as a stimulant and for treating congestion and asthma, according to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH). The plant contains ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, which are natural alkaloids, or nitrogenous organic compounds that cause a physiological response in humans. These chemicals are the basis on which amphetamines (including methamphetamine) were created.

The history of amphetamine

Nagai Nagayoshi, a Japanese chemist and pharmacologist, first isolated ephedrine in 1885. Only two years later, in 1887, Lazar Edeleanu, a Romanian chemist, synthesized amphetamine from ephedrine, according to the University of Arizona's Methamphetamine and Other Illicit Drug Education (MethOIDE) program.

In 1929, Gordon Alles, a U.S. biochemist, discovered that amphetamine had physiological effects. Soon after Alles' discovery, pharmaceutical companies developed amphetamine medications for treating congestion and asthma, according to a review published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2008. From 1933 to 1948, amphetamine was included in an over-the-counter nasal-congestion inhaler called Benzedrine.

Additional clinical trials found that amphetamine had positive effects on weight loss, narcolepsy and depression. It's popularity then grew during World War II as active service members from the U.S., Japan, Germany and England were administered the drug to treat mild depression and to enhance alertness and endurance.

Amphetamines have been used since then in the development of a variety of drugs, most notably Adderall and Ritalin, which treat ADD and ADHD. Addiction to amphetamines has been an issue since the 1940s, but it escalated in the 1980s with increased illicit production of methamphetamine, a very addictive stimulant known for its euphoric effects.

How amphetamines work

Amphetamines are used in treatments for ADD and ADHD, obesity, narcolepsy, and Parkinson's disease, according to CESAR.

"People with ADHD [are hypothesized to] have too little dopamine in the prefrontal cortex — the rational thinking, cognitive, planning part of your brain — the part of your brain that tells the rest of your brain to calm down," said Catherine Franssen, assistant professor of biopsychology and director of neurostudies at Longwood University in Virginia.

An amphetamine-based medication, such as Adderall or Ritalin, increases dopamine production in the connections between the prefrontal cortex and other locations in the brain, Franssen explained. This allows the prefrontal cortex to regain control.

Certain formulations of amphetamine, typically pseudoephedrine, are used in medications that treat cold symptoms, such as Sudafed, Franssen said. The amphetamine stimulants reduce the swelling of the blood vessels in the nose; this helps open up the airways, allowing for easier breathing. The medications are available without a prescription but are stored behind the pharmacy counter because they can be illegally used to brew methamphetamine, according to the American Council on Science and Health.

There's some evidence that amphetamines may treat obesity by acting as appetite suppressants. A 2015 clinical trial published in the journal Frontiers in Endocrinology reported that patients who took amphetamine medications experienced increased weight loss and motivation. The mechanism was unclear, and more research is needed to determine if amphetamines can be used for long-term weight loss and maintenance.

Amphetamine side effects

When taken properly, amphetamine-based medications can be safe and effective. But as with any prescribed medication, there are potential side effects.

Amphetamines can have a powerful effect on the body and brain, even when taken only once. According to MedlinePlus, side effects of taking amphetamines include:

- Enhanced mood

- Increased wakefulness and physical activity

- Increased respiration

- Insomnia

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure

- Irregular or rapid heartbeat

- Cardiovascular collapse

- Reduced appetite

- Changes in sex drive

- Hyperthermia

- Permanent brain damage

- Memory loss, confusion, paranoia and hallucinations

- Convulsions or Parkinson's-like tremors

- Cardiovascular collapse or stroke

Side effects such as enhanced mood are linked to the increase production and release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure.

Amphetamines also cause an increase in norepinephrine, the hormone involved with the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which is what controls our "fight-or-flight" mechanism, Franssen said. Norepinephrine causes the physical side effects, such as increased respiration, heart rate and blood pressure.

Together, those two chemicals can also have other mental effects.

"The increase of dopamine, as well as the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, [can lead to] hallucinations and psychosis, similar to schizophrenia," Franssen said.

Addiction and abuse

Amphetamines, particularly methamphetamine, can be highly addictive.

Amphetamine can cause the brain to produce such high amounts of dopamine that the brain compensates by getting rid of dopamine receptors, Franssen said, similar to how we cover our ears to decrease the volume when someone is shouting at us.

Removing these receptors decreases the person's ability to feel pleasure and can increase depression or suicidal thoughts when the person's not using the drug, according to American Addiction Centers. Those depressing feelings may drive people to continue using the drug so that the dopamine and the positive feelings it produces return.

In 1971, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs — now the U.S. DEA — classified all forms of amphetamine, including the highly addictive methamphetamine, as Schedule II drugs. The classification means the drugs have an accepted medical use but also a high potential for abuse.

Beginning in the 1980s, abuse of amphetamine skyrocketed as illegal methamphetamine production took off. This period also saw a surge in prescriptions of amphetamine drugs for treating attention deficit disorders. Abuse and medical use of amphetamines has continued to increase over the past decade.

It wasn't until 2004, according to the NCCIH, that the U.S Food and Drug Administration banned the sale of any supplement containing ephedrine, which had become a common supplement for athletes. The ban stemmed from a rise in the number of health issues related to the drug and several deaths of people looking to increase endurance and lose weight with ephedrine supplements, according to Harvard Health Publishing.

In the U.S., an estimated 4.8 million people ages 12 and up abused their amphetamine-based prescriptions and about 1.7 million used methamphetamine in 2015, according to a National Survey on Drug Use and Health. However, it's difficult to accurately track methamphetamine use, because the drug is manufactured and distributed illegally. Additionally, the majority of methamphetamines come from outside the U.S., where they are produced cheaply and illegally with little consequence.

In early 2018, The New York Times reported that methamphetamine use in the U.S. had greatly increased over the past decade. In Portland, Oregon, more than 200 people died from methamphetamine use in 2016; that was three times more than just 10 years earlier, the Times reported. Portland was just one such example of a location that inundated by methamphetamine use.

While the physical changes amphetamines cause in the brain are permanent, several therapeutic treatment programs that can help people overcome their addiction. The most-successful treatments include addiction education, family counseling, cognitive behavior therapy and peer-support groups.

Further reading:

- More about methamphetamine from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Amphetamine, past and present.

- Fact sheet on amphetamine from the U.S. DEA.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachel Ross is a science writer and editor focusing on astronomy, Earth science, physical science and math. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the University of California Davis and a Master's degree in astronomy from James Cook University. She also has a certificate in science writing from Stanford University. Prior to becoming a science writer, Rachel worked at the Las Cumbres Observatory in California, where she specialized in education and outreach, supplemented with science research and telescope operations. While studying for her undergraduate degree, Rachel also taught an introduction to astronomy lab and worked with a research astronomer.