Photos: Artifacts from a Watery Desert Grave

Entering the Tomb

A 16.5-foot (5 meter) shaft leads to a door below the Egyptian desert. Here, at the ancient quarry site of Gebel el-Silsila, archaeologists have discovered an ancient mass grave. Beyond the stone door is a water-filled tomb containing the remains of at least 50 people, including a child and two infants in stone sarcophagi. [Read more about the watery tomb discovery]

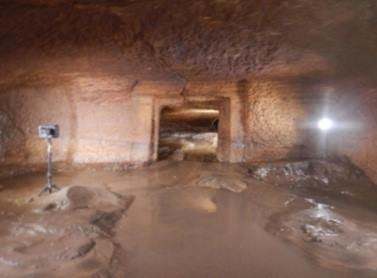

Flooded Tomb

In a tomb chiseled from bedrock, the ceiling is just tall enough for an adult to stand. Water enters the tomb from a natural fissure that has opened since it was first constructed around 3,500 years ago. Archaeologists use generator-powered pumps to continuously remove water from the tomb. They excavate by sitting in the warm, briny water on the tomb floor, running their hands through the silt layers, carefully sifting for bones and artifacts.

Buried with the Dead

All other tombs discovered at Gebel el-Silsila have been looted, so archaeologists are thrilled to have a site full of artifacts and skeletal remains. Looters did try to enter the tomb at one point; their efforts jumbled the silt and bones inside. But they weren't able to enter, so everything interred in the tomb remains safe. These green funerary amulets are among the artifacts sifted from the muddy water inside the main chamber.

Tomb Door

The door of the Gebel el-Silsila tomb. Any organic material in the tomb (wood, remains) has long since decayed away. This tomb is much different than others found at Gebel el-Silsila, which tend to be smaller niches meant for burials within a single family. The male adult bones found inside show signs of heavy labor, including back problems and healing broken bones, said assistant mission director and archaeologist John Ward. The women and children may have been family to these quarry laborers.

Afterlife servant

A shabti, or small human figurine, found in the flooded tomb. The presence of these shabtis indicates that the people buried inside the tombs were not slaves, Ward told Live Science. Shabtis were meant to work as laborers for the dead person in the afterlife, and slaves were not buried with these figurines.

Scarab amulet

A scarab-beetle amulet found within the Gebel el-Silsila tomb. Scarab beetles were important in ancient Egyptian iconography because they were associated with the sun god Ra. Ra was thought to roll the sun across the sky each day, much like scarab beetles roll balls of dung to nourish their young.

Lotus Blossom

An orange lotus blossom amulet found within the Gebel el-Silsila tomb. Other mass graves have been discovered in Egypt, including at the site of Luxor, where mummies in coffins were stacked head-to-toe. The tomb at Gebel el-Silsila may have been similar, Ward said, though it isn't clear why all of the deceased were put into the same chamber. The tomb also contains a second chamber, but it is still blocked by debris and silt.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Decorative flourish

A small bead that would have been worn in the hair, sifted from the muck of the new tomb. Gebel el-Silsila sits at a narrow spot of the Nile in Upper Egypt and was used as a quarry site starting in the 18th Dynasty, which started around 1550 B.C. The site was once thought to be mainly a work camp full of laborers, but the excavations of the Gebel el-Silsila project have revealed that it was actually a thriving community of men, women and children.

Sarcophagus

A tiny sarcophagus made for an infant sits in the flooded tomb. The tomb's main chamber held three sandstone-hewn sarcophagi, one containing and child and another containing an infant. A third infant-size sarcophagus is still being analyzed.

Removing a sarcophagus

Archaeologists carefully move one of the small sandstone sarcophagi from the flooded tomb. The excavation of the tomb has been ongoing for two years, and there are still layers of jumbled sand and bone to sort through before the main chamber is cleared. The team has also discovered bracelets, storage vessels, bowls, flasks and beer jugs amidst the sand and bones.

Shabtis

Additional shabtis found in the Gebel el-Silsila tomb. The atmosphere inside the tomb is almost reverential, Ward said. Archaeologists can only stay in the tomb for a few hours at a time because the air is so humid and stale; during their time in this watery underworld, they sit silently, all their attention on the sand they're sifting through their fingertips. "There's a lot of respect going on down there," he said.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.