Long-Hidden 'Pyramid' Found in Indonesia Was Likely an Ancient Temple

WASHINGTON — An enormous pyramid-like structure in Indonesia that may represent the remains of an ancient temple hid underground for thousands of years.

Scientists presented evidence of the remarkable construction Dec. 12 here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

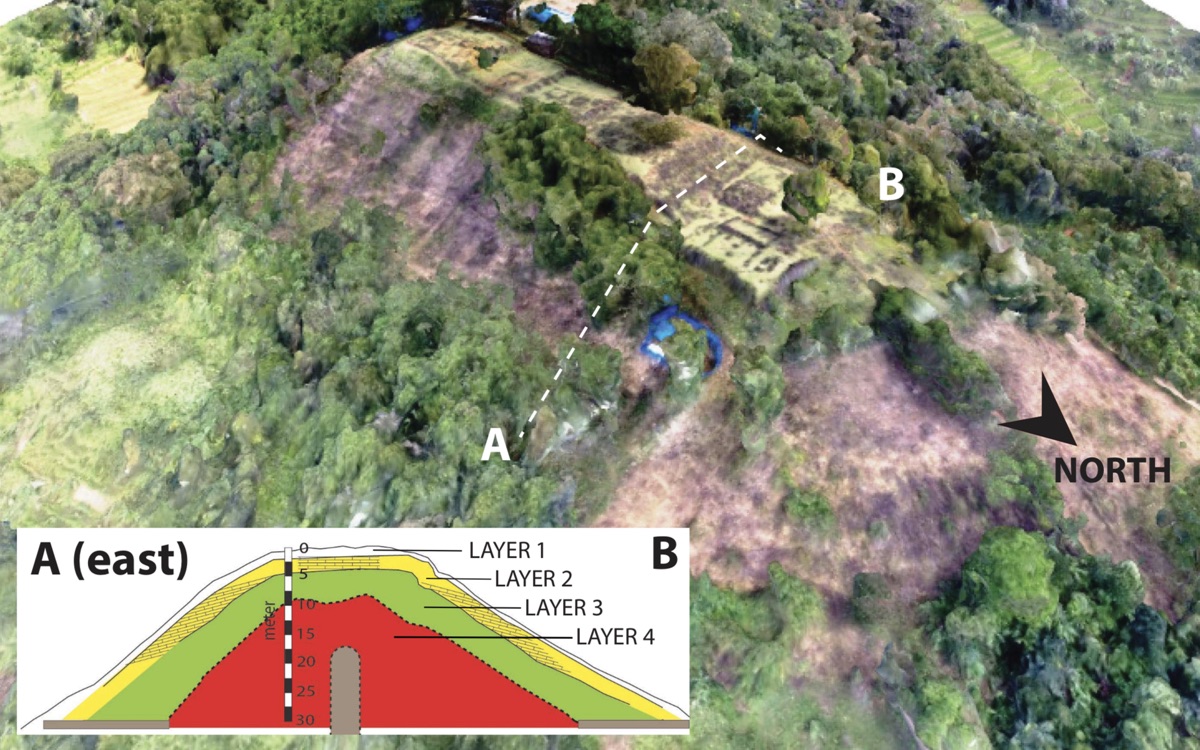

Located atop Mount Padang in West Java, the structure is topped by an archaeological site that was discovered in the early 19th century and holds rows of ancient stone pillars. But the sloping "hill" underneath isn't part of the natural, rocky landscape; it was crafted by human hands, scientists discovered. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

"What is previously seen as just surface building, it's going down — and it's a huge structure," said Andang Bachtiar, an independent geologist from Indonesia who supervised core drilling and soil analysis for the project.

Though the buried structure may superficially resemble a pyramid, it differs from similar pyramids built by the Mayans, Danny Hilman Natawidjaja, lead project researcher and a senior scientist with the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, told Live Science. While Mayan pyramids tend to be symmetrical, this structure is elongated, with what appears to be a half-circle in the front.

"It's a unique temple," Natawidjaja said.

He and his colleagues suspected that the exposed megalith might be more than it appeared, because some partly exposed features in the existing archaeological site didn't quite match the standing stones. The "peculiar" shape of the hill also stood out from the landscape, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's not like the surrounding topography, which is very much eroded. This looks very young. It looked artificial to us," Natawidjaja explained.

Using an array of techniques to peer underground — including ground-penetrating radar surveys, X-ray tomography, 2D and 3D imaging, core drilling, and excavations — the researchers gradually uncovered several layers of a sizable structure. It spread over an area of around 15 hectares (150,000 square meters) and had been built up over millennia, with layers representing different periods.

At the very top were pillars of basalt rocks framing step terraces, with other arrangements of rock columns "forming walls, paths and spaces," the scientists reported at AGU. They estimated this layer to be about 3,000 to 3,500 years old.

Underneath the surface, to a depth of about 10 feet (3 m), was a second layer of similar rock columns, thought to be 7,500 to 8,300 years old. And a third layer, extending 49 feet (15 m) below the surface, is more than 9,000 years old; it could even date to 28,000 years ago, according to the researchers. Their surveys also detected multiple chambers underground, Natawidjaja added.

Today, local people still use the exposed site at the top of the structure as a sacred destination for prayer and meditation, and this could also be how it was used thousands of years ago, Natawidjaja said.

- 25 Cultures That Practiced Human Sacrifice

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- In Photos: Enormous Ancient Mexican Temple

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.