Archaeology Discoveries to Watch for in 2019

A new hoard of 1,400 tablets from a lost city in Iraq, new clues to a massive void in the Great Pyramid and the discovery of an ornately decorated Easter egg that belonged to the Russian royal family are just some of the cool archaeological discoveries that we might see in 2019.

Great Pyramid void

In 2019, we can expect to get more information on a large void, discovered above the so-called grand gallery inside the Great Pyramid of Giza — a hallway that leads to the sarcophagus of pharaoh Khufu, for whom the pyramid was constructed. The void is more than 98 feet (30 meters) long. Archaeologists spotted the empty space in 2017, publishing details on their study in November 2017 in the journal Nature. But it's unclear whether that space is a closed-off ancient construction corridor, a hidden burial chamber or a series of small chambers.

They found the void using cosmic particles known as muons. These particles, which form when cosmic rays interact with Earth's upper atmosphere, can travel through stone, but they lose energy and decay when doing so. By measuring the number of muons flowing through an object from a particular direction, the researchers could find out the density of that object (or void).

Additional muon tests that are taking place right now may reveal more information about what exactly the void is. Preliminary results from the new series of tests will likely be released sometime in 2019.

A New Cave near Qumran

In 2019, we may see the discovery of a new cave, possibly containing scrolls, near Qumran, the site where the Dead Sea Scrolls were buried in nearby caves. The Dead Sea Scrolls consist of the fragments of 900 texts discovered in 12 caves. Scholars widely believe that a sect called the Essenes wrote many of the scrolls at Qumran. Both 2017 and 2018 saw the discovery of looted caves that have evidence that they held Dead Sea Scrolls in the past, and another cave will most likely be discovered in 2019.

Archaeologists have been working in the area for several years as part of a project that aims to discover and excavate any caves in the Judean Desert that may contain artifacts. The program launched after a surge in looting that saw some scrolls appear on the antiquities market. Aside from excavation, archaeologists are using a variety of remote-sensing techniques to peer beneath the surface before deciding where to excavate.

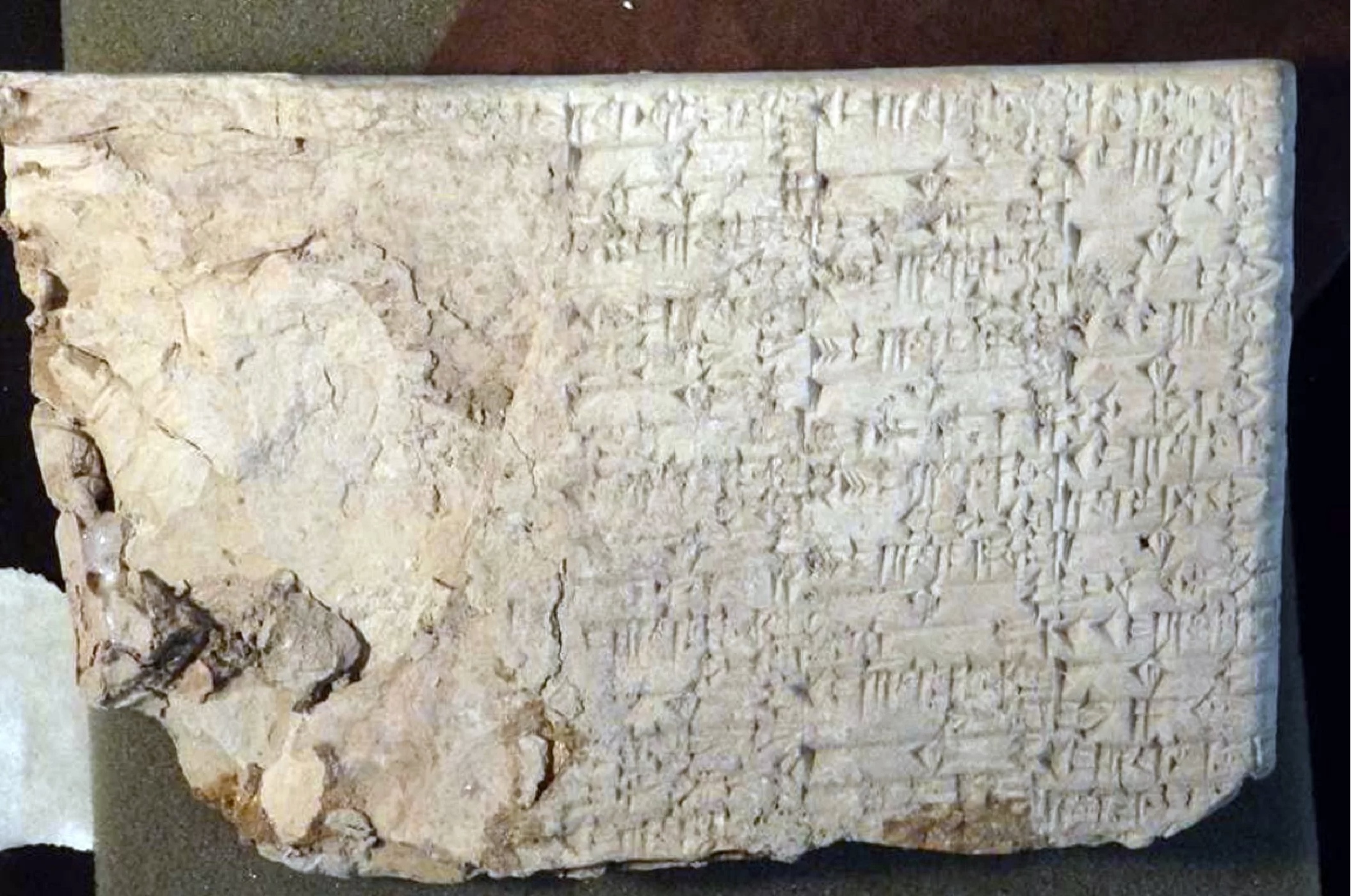

Immense hoard of tablets from lost city in Iraq

In 2019, an immense hoard of 1,400 tablets from the lost city of Irisagrig, in Iraq, may be revealed in the United States. They will be found in a private collection held by an owner who will want to maintain anonymity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2018, news broke that the looted artifacts seized from the retail chain Hobby Lobby (whose owners also founded the new Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C.) included about 200 cuneiform tablets that are from the lost city of Irisagrig in Iraq. This new hoard will not be owned by Hobby Lobby but rather will have a different owner.

Tablets from Irisagrig have been appearing on the antiquities market over the past two decades. While looters know the city's location, archaeologists don't. The tablets that have appeared on the antiquities market tell of a city that flourished 4,000 years ago, containing palaces with well-fed dogs. It's possible that some of the new tablets will contain clues that may allow archaeologists to find this lost city.

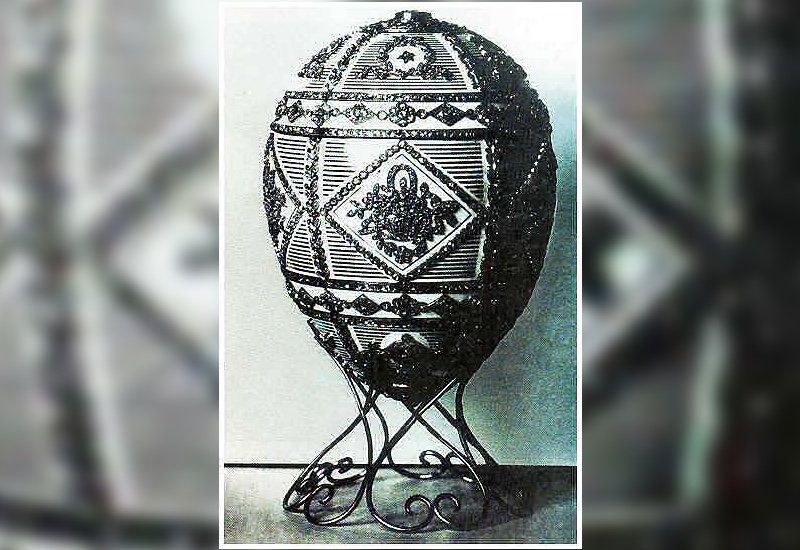

Lost Easter eggs of the czars

Between 1885 and 1916, the jewelry company Fabergé crafted about 50 ornately decorated Easter eggs for the Russian royal family. In the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution, some of these eggs went missing.

In 2017, Live Science revealed the existence of documents that show that two massive hoards of art and antiques were sent to New Orleans from the Soviet Union and Turkey in 1991 and 1992. The combined value of the two shipments was $164 million, which amounts to $285 million today. While the documents don't state precisely what was in those shipments, it's possible that one of the missing Easter eggs was among the treasures sent to the United States. There have been rumors over the years that some of the eggs made their way to private collections in the United States, and, in 2019, we may see one of the missing eggs come out of hiding.

Khufu Papyri

In 2013, archaeologists working at the site of Wadi al-Jarf, by the Red Sea, announced the discovery of papyri dating back about 4,500 years, to the reign of Khufu, the pharaoh who built the Great Pyramid. A study of the papyri has revealed that it contains a logbook of an inspector named Merer, who led a team that performed tasks that aided in the construction of the Great Pyramid and other building projects in Egypt.

So far, only part of this logbook has been deciphered and analyzed, with the results yielding information on an ancient harbor located near the Great Pyramid and on the movement of limestone from the site of Tura to the Great Pyramid. In 2019, we may learn more about other sections of the logbook that are currently being deciphered and analyzed.

- Archaeologists Are Hot on the Trail of These 16 Spectacular Mysteries

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- 25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.