Going viral: 6 new findings about viruses

Researchers are still uncovering new secrets about these tiny invaders.

Viruses were discovered in 1892, and yet even in 2022, researchers are still uncovering new secrets about these tiny invaders. Viruses are not quite living things and have no way to reproduce on their own. Instead, they're made of genetic material, usually DNA or its chemical cousin RNA, that's wrapped in a protein coating. Because of their ability to integrate their genetic code into the code of their host, viral genes are found hidden in the genetic codes of many living things all over the world, from bacteria to humans, in habits from deep in the ocean to inside Arctic ice, and even sometimes falling from the sky.

The dawn of the COVID-19 pandemic has also led to a surge in research on coronaviruses — especially SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 — as well as research into which pathogens may cause the next pandemic. .

Here are six new things scientists have recently learned about viruses:

The novel coronavirus mutates in a sneaky way

Since SARS-CoV-2 first appeared in Wuhan, China, in 2019, it has developed multiple mutations resulting in numerous variants popping up around the world. A study published in February 2021 in the journal Science shed light on how the virus mutates so easily and why these mutations help it "escape" the body's immune response.

The study researchers found that SARS-CoV-2 often mutates by simply deleting small pieces of its genetic code, Live Science previously reported. Although the virus has its own "proofreading" mechanism that fixes errors as the virus replicates, a deletion won't show up on the proofreader's radar.

What's more, for SARS-CoV-2, these deletions frequently show up in similar spots on the genome. These are sites where people's antibodies would bind to and inactivate the virus. But because of these deletions, many antibodies cannot recognize the virus.

These deletions are like a string of beads where one bead is popped out. That might not seem like a big deal, but to an antibody, it's "completely different," study senior author Paul Duprex, director of the Center for Vaccine Research at the University of Pittsburgh, told Live Science. "These tiny, little absences have a big, big effect."

Which virus will cause the next pandemic?

SARS-CoV-2 is the latest pathogen to "spill over" from animals to people, but hundreds of thousands of other viruses lurking in animals could pose a similar threat. A new online tool called SpillOver, described in a study published in April 2021 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, ranks viruses by their potential to hop from animals to people and cause pandemics.

To come up with the rankings, the researchers created a credit-like score for viruses as a way of assessing and comparing their risks, Live Science previously reported. Then, they used the tool to rank 887 wildlife viruses, including some that are already zoonotic (meaning they've hopped from animals to people, including Ebola and SARS-CoV-2) and others that haven't yet jumped from animals to people.

Among viruses that aren't yet zoonotic, the top-ranking virus — or the one that is most likely to both hop from animals to people and cause a pandemic — was coronavirus 229E (bat strain), which belongs to the same viral family as SARS-CoV-2 and infects bats in Africa. Another top-ranking virus is coronavirus PREDICT CoV-35, which also belongs to the coronavirus family and infects bats in Africa and Southeast Asia.

The researchers hope their open-access tool can be used by other scientists, policymakers and public health officials to prioritize viruses for further study, surveillance and risk-reducing activities, such as possibly developing vaccines or therapeutics before a disease spills over.

Thousands of new viruses found in the world's oceans

Researchers recently identified more than 5,000 new virus species in the world's oceans.

The study researchers analyzed more than 35,000 water samples from around the globe, hunting for RNA viruses, or viruses that use RNA as their genetic material, Live Science previously reported.

The diversity of the newfound viruses was so great that the researchers have proposed doubling the number of taxonomic groups needed to classify RNA viruses, from the existing five phyla to 10 phyla. (Phylum is a broad classification in biology just below "kingdom.")

The five newly proposed phyla are named Taraviricota, Pomiviricota, Paraxenoviricota, Wamoviricota and Arctiviricota, according to the study, published in April 2022 in the journal Science.

All RNA viruses contain an ancient gene called RdRp, which is billions of years old, and it helped the researchers home in on RNA sequences in the ocean. Because this gene is so old, studying how it evolved over time could lead to a better understanding of how early life evolved on Earth, the authors said.

Viruses' "Z genome" more common than thought

Some viruses have DNA with a unique genetic "letter" known as Z, and new research has found that this "Z-genome" is more common than previously thought.

DNA is made up of chemical compounds called nucleotides, and each nucleotide contains one of four nitrogen bases: guanine (G), cytosine (C), thymine (T) and adenine (A). Together, these "letters" make up the genetic code of DNA.

But in the 1970s, scientists discovered a type of virus called a cyanophage that used a chemical called 2-aminoadenine, dubbed "Z," in place of adenine. So instead of using the genetic alphabet "ATCG", these viruses used the alphabet "ZTCG," Live Science previously reported.

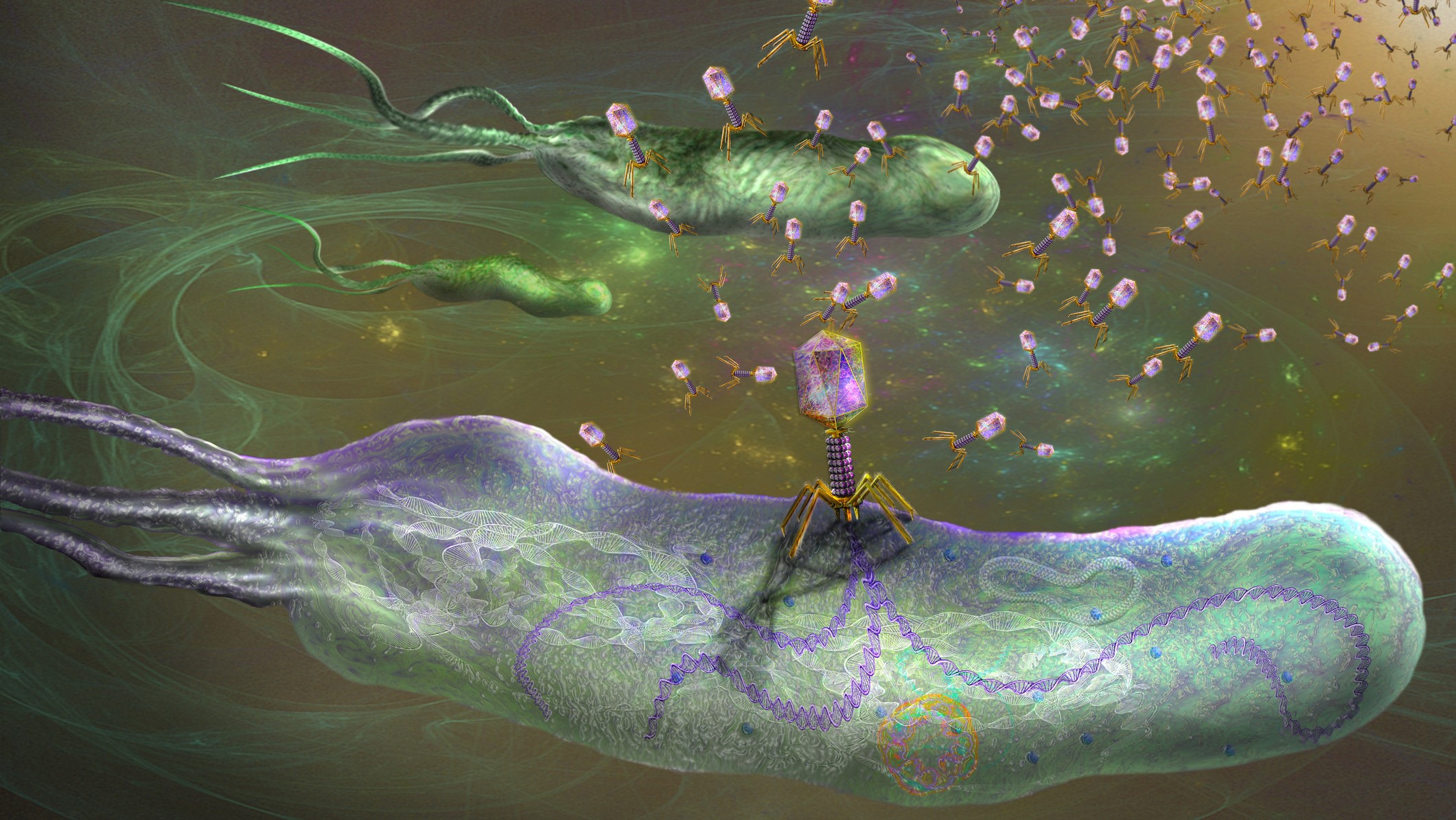

Researchers initially believed that the Z genome was very rare, present in only one species of virus, but a study published in April 2021 in the journal Science found that the Z genome was more common than thought, present in more than 200 types of viruses. All of the viruses that contain the Z genome are bacteriophages, or viruses that infect bacteria.

The Z genome may give these viruses some advantages, including making their DNA more stable at higher temperatures, the researchers said.

Human gut has thousands of never-before-seen viruses

Sometimes, to discover new microorganisms, scientists need not look farther than our own bodies. In a study published in February 2021 in the journal Cell, researchers described more than 70,000 previously unknown viruses hidden in the human gut, Live Science previously reported.

The researchers analyzed more than 28,000 human-gut microbiome samples from 28 countries. All of the newfound viruses were bacteriophages (or phages), or viruses that infect bacteria.

The researchers note that a single person would carry around only a fraction of the newly discovered viruses, and that the vast majority of these viruses are not likely harmful to people.

"As bacterial communities are a critical component of our gut, it's not difficult to imagine that phages could be playing a key role in maintaining a healthy equilibrium in our intestine," study lead author Luis Camarillo-Guerrero, a bioinformatics scientist at the biotech company Beam Therapeutics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and former postdoctoral candidate at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the U.K., told Live Science.

Viruses are literally falling from the sky

For years, researchers wondered why viruses that are genetically similar to each other can be found great distances apart on Earth. Recently, they found the answer: Viruses can travel through the atmosphere on air currents, Live Science previously reported. In a paper published in January 2018 in the Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology, researchers reported that viruses can hitch rides on particles of soil or water and swing high into a layer of the atmosphere called the free troposphere, and then eventually plop down in a completely new spot.

The researchers also found that when viruses reach the level of the free troposphere, which is found approximately 8,200 to 9,800 feet (2,500 to 3,000 meters) above Earth's surface, they can travel much farther than would be possible at lower altitudes. It turns out that the free troposphere is teeming with viruses, and due to the action of the air currents within it, a given square meter of Earth's surface may be showered with hundreds of millions of viruses in a day, the researchers said.

"Every day, more than 800 million viruses are deposited per square meter above the planetary boundary layer — that’s 25 viruses for each person in Canada," study co-author Curtis Suttle, a virologist and professor with the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia, said in a statement.

Karen Rowan contributed to this article.

This article was originally published on Dec. 30, 2018. It was rewritten on April 18, 2022.

Original article on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents