Laser-Blasted Plasma Is Cooler Than Deep Space...Literally

Researchers who make the coldest plasmas in the universe just found a way to make them even colder — by blasting them with lasers.

The scientists cooled the plasma to around 50-thousandths of a degree above absolute zero, about 50 times colder than in deep space.

This chilly plasma could reveal how similar plasmas behave at the centers of white dwarf stars and deep in the core of gas planets like our cosmic neighbor, Jupiter, researchers reported in a new study. [The Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics]

Plasma is a type of gas, but it's different enough to be recognized as one of the four fundamental states of matter (alongside gas, liquid and solid). In plasma, a significant number of electrons have been separated from their atoms, creating a state where free electrons zip around ions, or atoms that have either a positive or negative charge.

Temperatures in naturally occurring plasma are typically very high; for example, plasma on the surface of the sun seethes at 10,800 degrees Fahrenheit (6,000 degrees Celsius). By cooling plasma, scientists can make more detailed observations in order to better understand its behavior under extreme conditions, like those roiling our gas giant neighbors.

Be more chill

So why use lasers to help the plasma chill out?

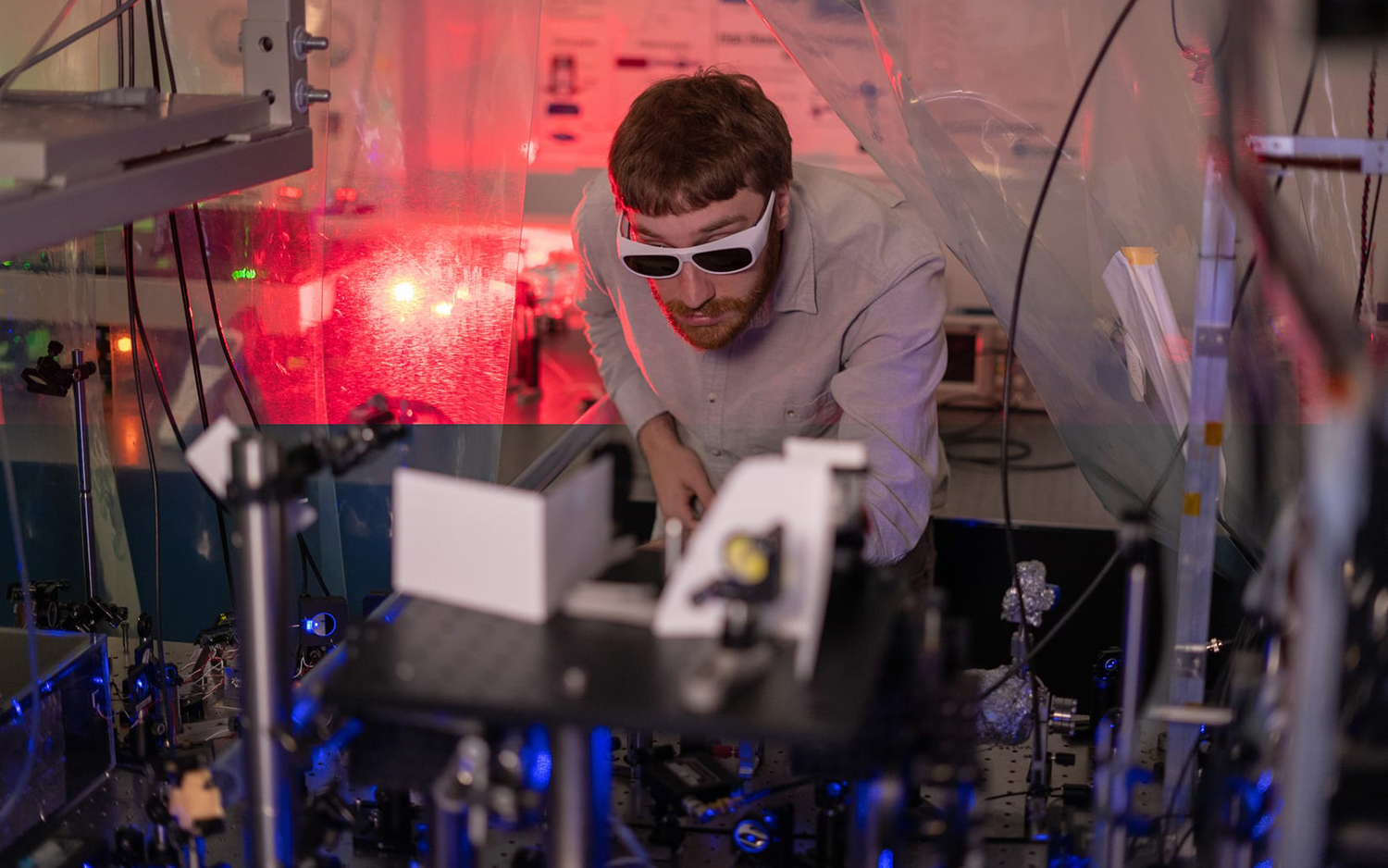

"The laser cooling takes advantage of the fact that light has momentum," lead study author Thomas Killian, a professor of physics and astronomy at Rice University in Texas, told Live Science. "If I have an ion in the plasma and I have a laser beam scattering light off that ion, every time that ion scatters a photon it gets a push in the direction of the laser beam," Killian said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This means that if a laser beam opposes the ion's natural motion, every time the ion scatters light it loses some momentum, which slows it down.

"It's like walking uphill or in molasses," he said.

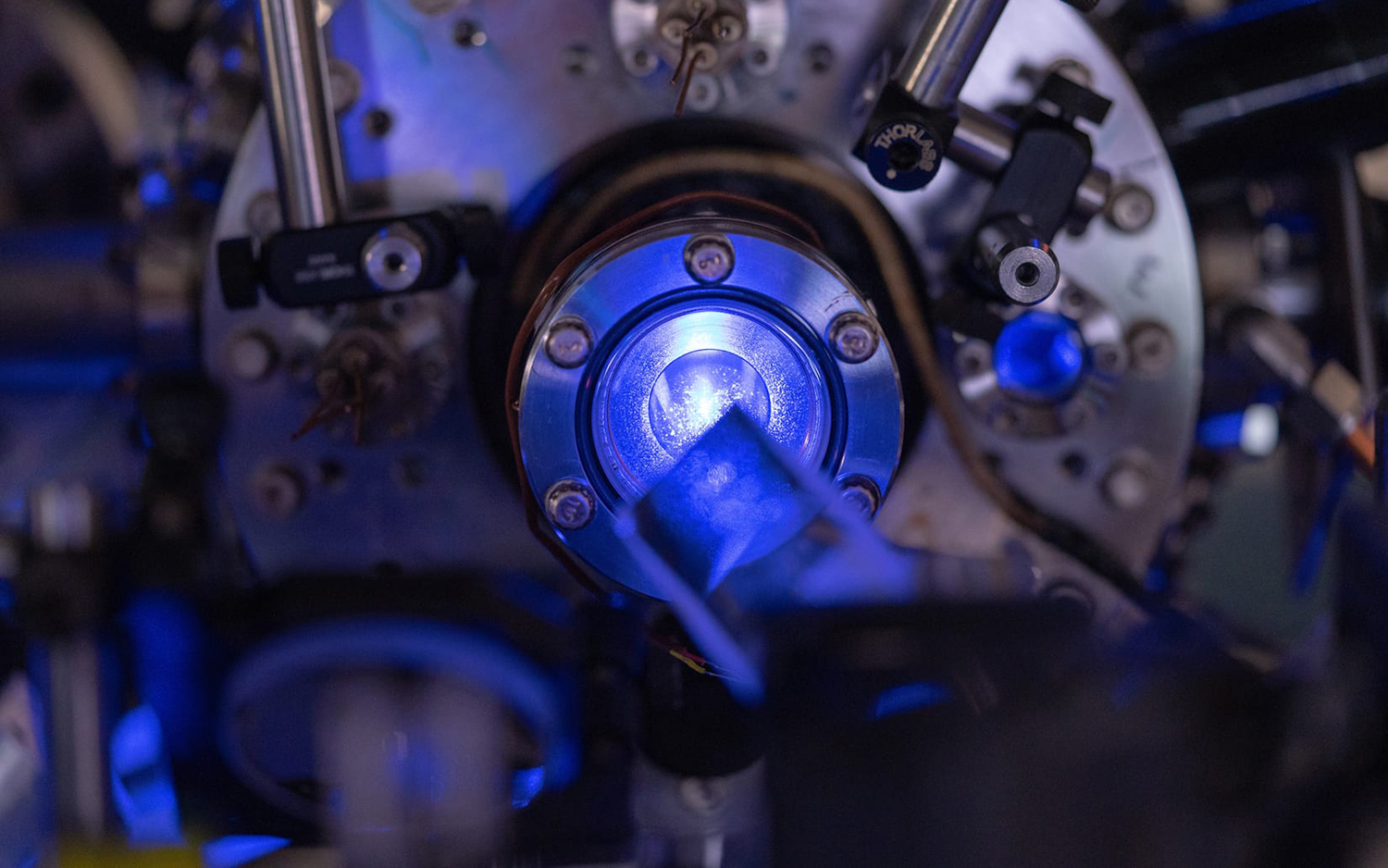

For their experiments, Killian and his colleagues produced small amounts of neutral plasma — plasma with a relatively equal number of positive and negative charges — vaporizing strontium metal and then ionizing the cloud. The plasma dissipated in less than 100 millionths of a second, which didn't leave the scientists much time to cool it down before it disappeared. For the laser cooling to work, they needed to precool the plasma, slowing the ions down even more. In the end, the resulting plasma was about four times colder than any that had ever been created before, the study authors reported.

Assembling the pieces needed to generate highly cooled plasma took about 20 years, though the experiments themselves lasted less than a fraction of a second — and there were thousands upon thousands of experiments performed, Killian said.

"When we create a plasma it only lives for a couple hundred microseconds. Every 'make a plasma, laser-cool it, look and see what happened' is less than a millisecond," he said. "It takes days and days to actually build up enough data to say, 'Ah, this is how the plasma is behaving.'"

Going colder

The study's findings invite plenty of questions about how ultracold plasma may interact with energy and matter; finding answers could help to create more accurate models of white dwarf stars and gas giant planets, which have plasma deep in their interiors that behaves similarly to the plasma cooled in the lab.

"We need better models of those systems so we can understand planet formation," Killian said. "This is the first time that we've had a tabletop experiment in which we can actually measure things to feed into those models."

Creating plasma that's even colder may also be within reach, which could further transform scientists' understanding of how this mysterious form of matter behaves, Killian told Live Science.

"If we can cool it another order of magnitude, we can can get close to predictions of where the plasma may actually become a solid — but a bizarre solid 10 times less dense than any solid that people have ever made," Killian said.

"That would be very, very exciting," he added.

The findings were published online Thursday (Jan. 3) in the journal Science.

- States of Matter: Plasma

- Science Fact or Fiction? The Plausibility of 10 Sci-Fi Concepts

- Is a Real Lightsaber Possible? Science Offers a New Hope

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the temperature of the surface of the sun from 3.5 million degrees Fahrenheit (2 million degrees Celsius), which represents the star's hotter interior.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.