Here's Where J.K. Rowling Got Her Magical Ideas for Harry Potter (Photos)

A History of Magic

Harry Potter fans rejoice — there are two tours about our wizarding hero in New York City right now. Harry Potter: A History of Magic is showing at the New-York Historical Society through the end of January. And Museum Hack’s The Boy Wizard tour is magicking at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as the de Young Museum in San Francisco year round.

Both delve into the history of magic seen at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. For instance, did you know "hocus pocus" — seen in "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets" when Harry menacingly teases his cousin Dudley — likely comes from the religious blessing "Hoc est corpus meum"? According to Museum Hack, the shorter "spell" is likely a perversion of the original Latin phrase, which means "this is my body."

Bezoar stone

In Harry's first potions class, Professor Snape exposes our hero's ignorance of the wizarding world by asking him about bezoars (BE-zors), supposedly powerful antidotes to poison. But these stones aren't unique to witches and wizards; bezoars also also appear in the Muggle (non-magical) world. Bezoars are indigestible fibers that clump together in the digestive system, especially in those of goats, cows and elephants. Here is one encased in a 17th-century gold filigree case. There are other bezoars at the Met, Museum Hack pointed out.

But don't expect bezoars to cure you if you're poisoned. They're not really antidotes.

Sorcerer's stone

In "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" (Scholastic Press, 1998), the evil wizard Voldemort is after something powerful (beware, spoiler ahead): A stone that makes gold and bestows immortality on its owner.

But the sorcerer's stone — also known as the philosopher's stone — isn't a new idea. The famous 16th century Ripley Scroll, shown here, is a nearly 20-foot-long (6 meters) scroll that offers a detailed recipe about how to make such a prize. You can see the whole scroll here. In real life the stone was also thought to convey immortality upon its finder.

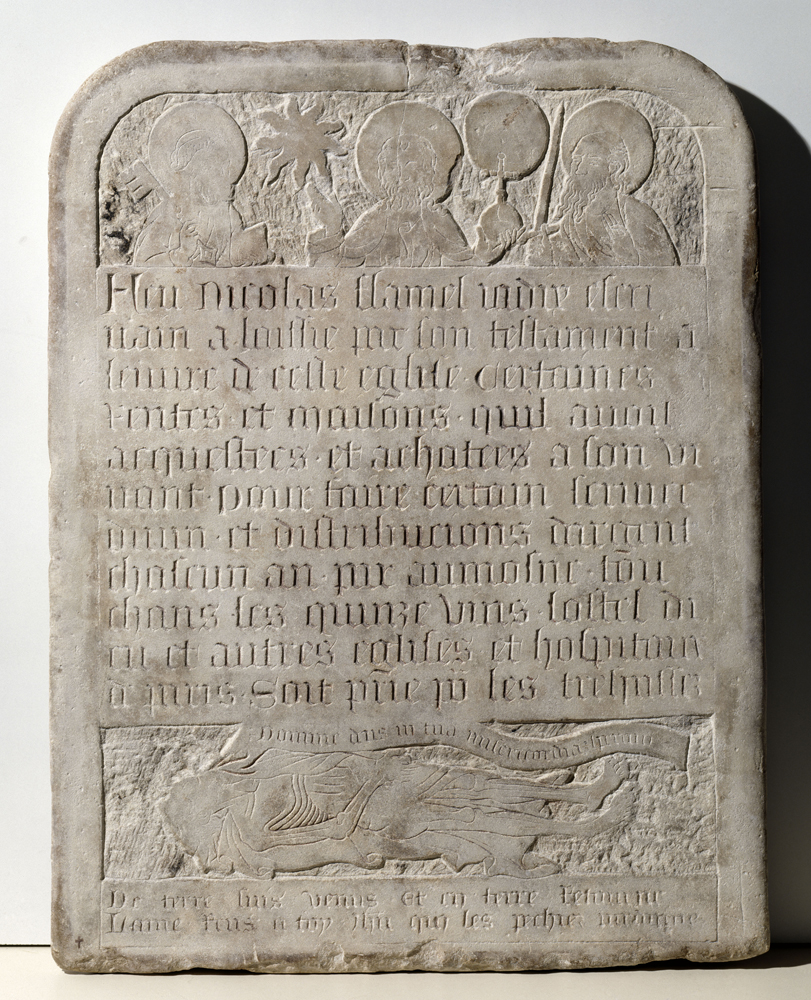

Nicolas Flamel

Nicholas Flamel is a key character in the Potterverse. After all, he created the Sorcerer's stone.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Flamel was actually a real person who died in 1418. His tombstone is above. Flamel was a landlord in medieval Paris, and there were many rumors that he had discovered the Sorcerer's stone. Even more intriguing, when his grave was exhumed, the body was missing.

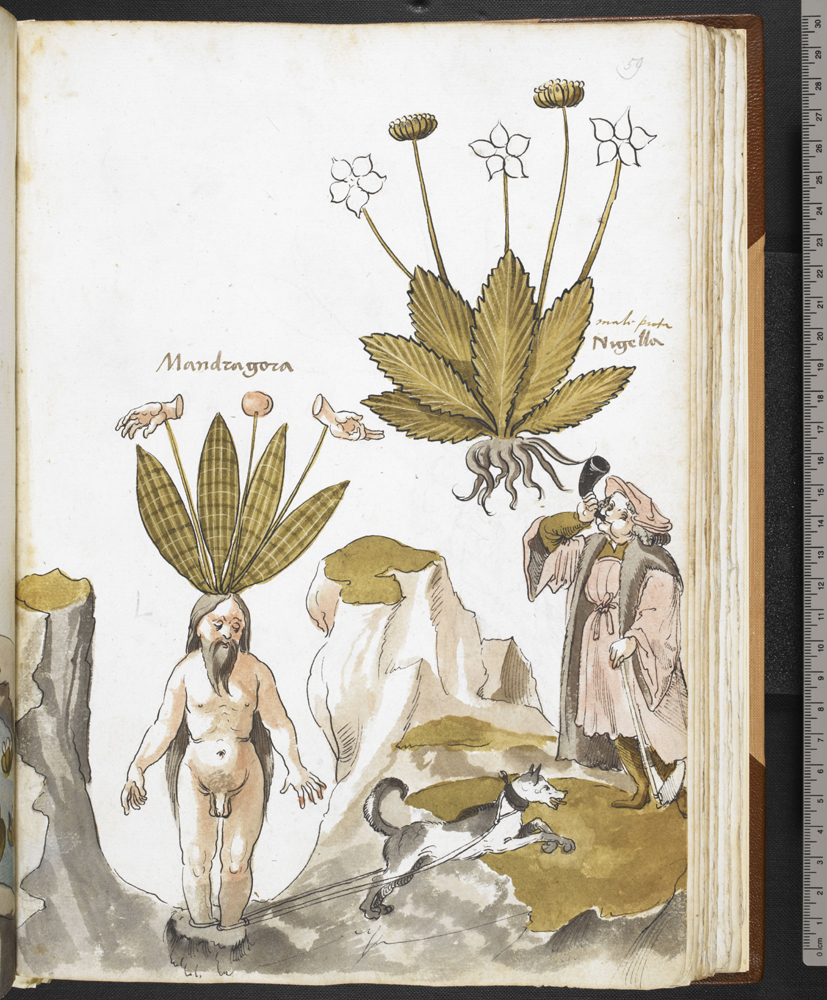

Mandrakes

Harry Potter and his friends come across the mandrake when they take herbology at their magic school. It is truly a peculiar plant. Harry learns that its cries can kill a person, so he dons earmuffs to protect himself. Luckily, these magical plants can also cure people who have been petrified, as we learn in "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets" (Scholastic Press, 2000).

In antiquity, the resemblance of the mandrake's root to the human form prompted many cultures to attribute special powers to the plant, according to the New-York Historical Society. In reality, the mandrake's roots and leaves are poisonous and can cause hallucinations.

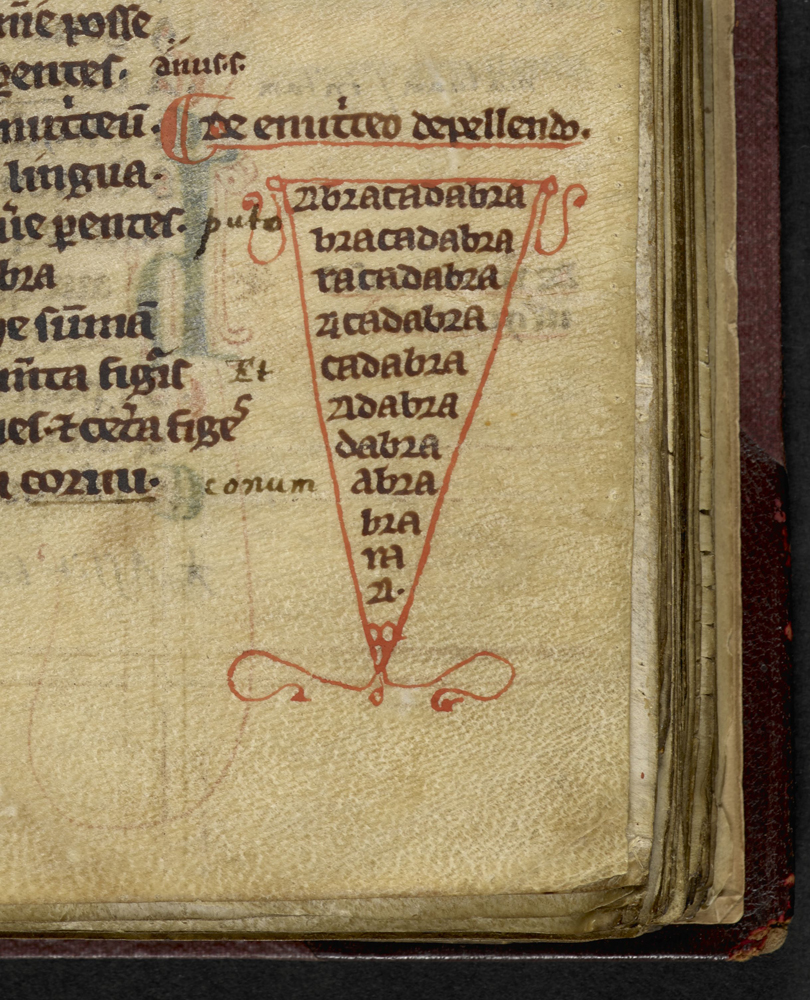

Abracadabra

In ancient times, "abracadabra" was thought to be a charm with healing powers. In the 13th-century medical book "Liber Medicinalis," readers are instructed to write out the entire word and omit one letter on each subsequent line. Then, the charm could be worn as an amulet around the neck to drive out malaria-induced fever.

According to a 2004 interview, Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling revealed that the killing curse "avada kedavra" comes from abracadabra.

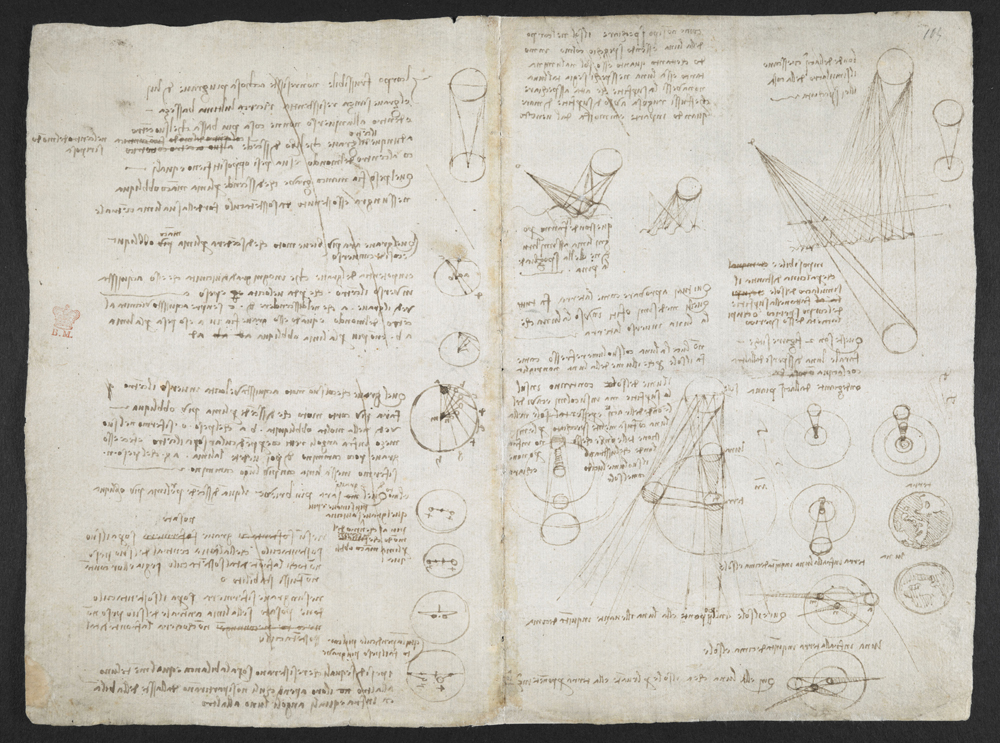

Astronomy

Harry Potter studied astronomy at Hogwarts, and he was in good company. Here's the notebook of Leonardo da Vinci's, one of history's great astronomers and innovators. In the notebook, written between 1506 and 1508, da Vinci wrote backwards in Italian from right to left, so that his work wouldn't be plagiarized.

Here, da Vinci shows the sun and moon revolving around Earth, reinforcing the (incorrect) view that Earth was at the center of the universe. Da Vinci also (wrongly) believed that the moon was covered with water and that its surface reflected light like a convex mirror, according to the New-York Historical Society.

Star-filled map

Harry Potter studied the night sky with Professor Aurora Sinistra, the witch who taught astronomy at Hogwarts. Perhaps he would have benefited from this celestial globe, which shows the position of the stars in the sky, created in Venice in 1699. It was made by Vincenzo Coronelli, a Franciscan friar and cosmographer who was considered one of the greatest globemakers in the world.

Oracle bones

Forever logical, Professor Minerva McGonagall calls divination "one of the most imprecise branches of magic." But J.K. Rowling didn't conjure this branch of magic out of thin air. Here is a Chinese oracle bone dated to the Shang Dynasty, which lasted from 1600 B.C. to 1046 B.C.

The oxen shoulder blade was engraved and then heated with metal sticks, which caused the bone to break. Then, a shaman read the resulting patterns (reportedly made from the spirits of ancestors) to answer questions about the emperor's health and affairs, as well as warfare, agriculture and natural disasters, according to the New-York Historical Society.

Werewolves

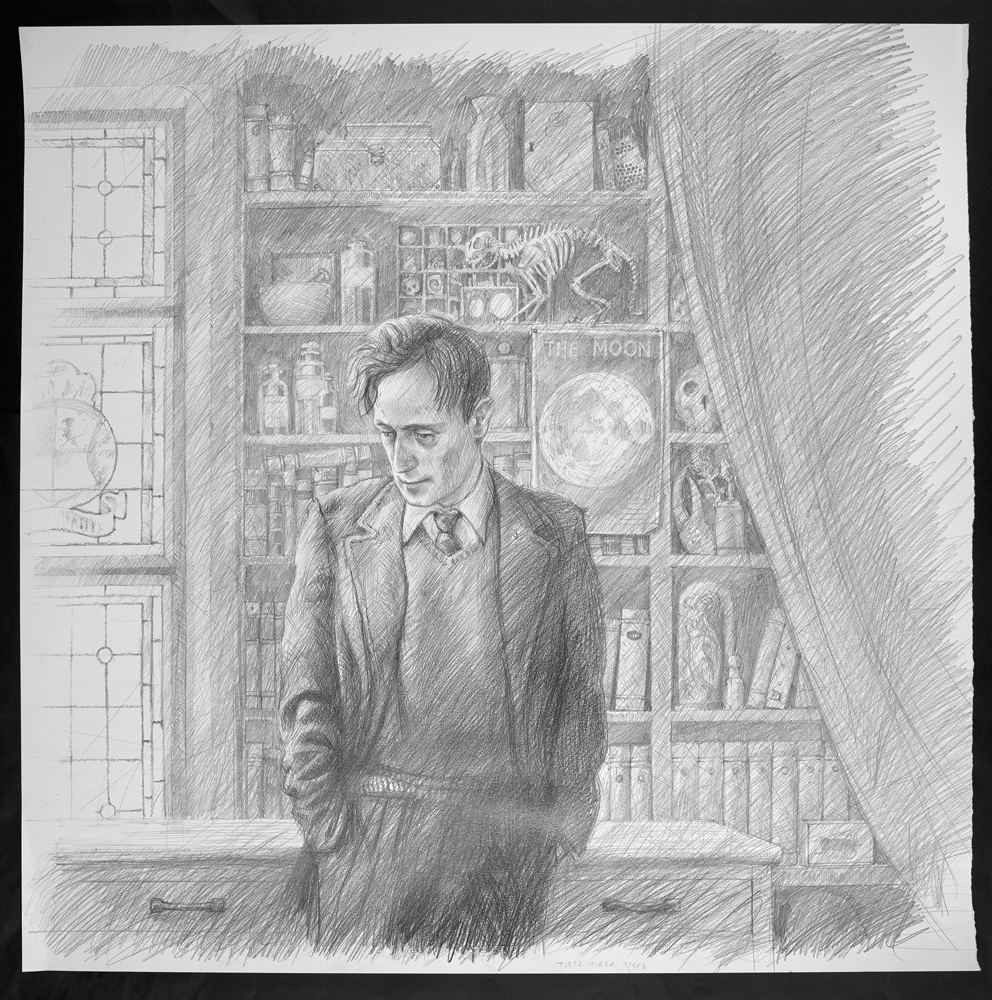

Remus Lupin, who teaches defense against the dark arts, is one of Harry's favorite professors. But Lupin is also (spoiler ahead) a werewolf. In this illustration, Lupin averts his gaze from the viewer while the full moon is ominously shown in the background.

The surname Lupis is Latin for wolf and the name Remus is from one of the legendary founders of Rome, who was suckled by a wolf.

Owls

Students at Hogwarts can have a pet cat, toad or owl, Harry learns as he prepares for his first year at school. Much to Harry's delight, Hagrid, the Hogwarts groundskeeper, buys him a snowy owl named Hedwig.

Snowy owls (Bubo scandiacus) — shown here in a 1829 watercolor painted by John Audubon — hunt during the day and the early evening. In this watercolor, the owls are shown at twilight with a gathering snowstorm in the background.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.