Ancient Sea Monster's Head Holds Big Teeth … and Fake Bones

A new analysis of a nearly 200-million-year-old sea-monster skull has surprised scientists, but not merely because the skull was enormous or because it was exquisitely preserved and not squashed, like many other Jurassic-period fossils are.

What took scientists aback was that the fossil had fake "bones" inside it.

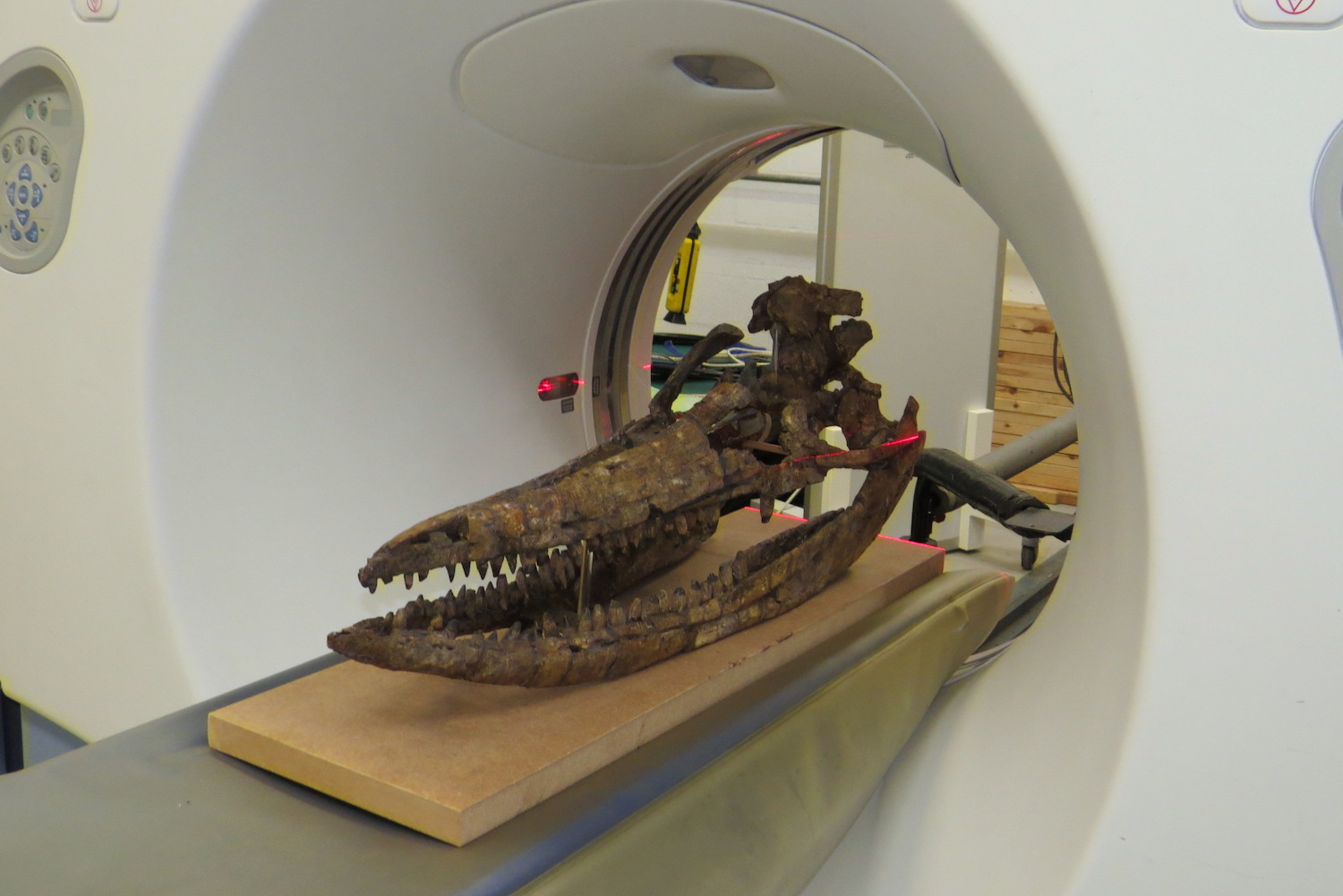

The researchers already knew that, decades ago, curators added wood, clay and plaster to the skull of the ichthyosaur — a dinosaur-age marine reptile that looks like a modern dolphin — to help stabilize the specimen. But after the researchers removed this clay and looked at computed tomography (CT) scans of the skull, they were startled to learn that the skull contained still more fake material. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

"We were unaware of clay and reconstructed materials that still remained, including in some of the braincase bones," said study lead researcher Dean Lomax, a paleontologist and visiting scientist at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at The University of Manchester, in England. "So, based on the CT scans, I was surprised to see how particularly well the bones had been sculpted to match the color and shape."

Unfortunately, the researchers weren't able to remove the newly discovered clay, "because it may result in those bones becoming fragmented or damaged," Lomax told Live Science in an email.

Even so, the new analysis is still a big step forward in ichthyosaur research. It's the first time researchers have shared a digital reconstruction of a large marine-reptile skull and mandible (lower jaw) with both scientists and the public, Lomax said.

The giant skull was found in a farmer's field in Warwickshire, England, in 1955. But it was never formally studied until now.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Over the years, researchers thought the skull represented a newfound species, though they later attributed the skull to the common ichthyosaur species, Ichthyosaurus communis. Now, the new analysis reveals that the fossil is neither: Instead, it's Protoichthyosaurus prostaxalis, a rare, early Jurassic ichthyosaur that used its pointy teeth to dine on fish.

And it's not just any P. prostaxalis skull; it's the largest on record. The newly analyzed skull is almost twice as long as any other known P. prostaxalis skull, Lomax said. The fossil is at least 2.6 feet (0.8 m) long, with its lower jaw extending 2.8 feet (0.87 m). Given that P. prostaxalis' skull length is usually between 20 and 25 percent of its total body length, this individual was likely between 10.5 and 13 feet (3.2 and 4 m) long during its lifetime in the dinosaur age, the researchers wrote in the new study.

The project, which began in 2014, took a few unexpected turns. At first, the researchers simply planned to clean the specimen, CT scan it and put it back on display, said study co-researcher Nigel Larkin, an affiliated researcher at the University of Cambridge's Museum of Zoology in England. But soon, they realized that the fossil was one of the best-preserved ichthyosaur skulls from the Jurassic period and that it even contained preserved pieces of the braincase (the bone that holds the brain).

"Only a handful of similar-aged ichthyosaur braincase bones are known, and most are known from isolated elements — that is, individual bones not associated with the skull or skeleton," Lomax said. The newly studied fossils show how this ichthyosaur's braincase bones fit together, where the brain would have sat and how these bones differ from those of other ichthyosaurs. The CT scans even showed the "long canals within the skull bones that originally contained blood vessels and nerves," study co-researcher Laura Porro, a lecturer in cell and developmental biology at University College London, said in a statement.

So, what did the sea monster's brain look like? It's hard to say.

"As for the brain itself, unfortunately, the braincase isn't complete enough that we can give specific measurements of the brain's size or shape. But what we can say is that, based on the shape of the bones around the brain (and from preserved impressions of structures that surrounded the brain), its braincase was quite different [from those of] other ichthyosaur species," Lomax said.

The skull is now on display at Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum. The study was published online today (Jan. 8) in the journal PeerJ.

- Photos: Uncovering One of the Largest Plesiosaurs on Record

- In Images: Graveyard of Ichthyosaur Fossils in Chile

- Image Gallery: Photos Reveal Prehistoric Sea Monster

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.