Extinct Human Relative from 'Miracle' Excavation Moved Like a Chimp

An ancient human relative known as "Little Foot" likely walked more like a chimpanzee than like a modern human.

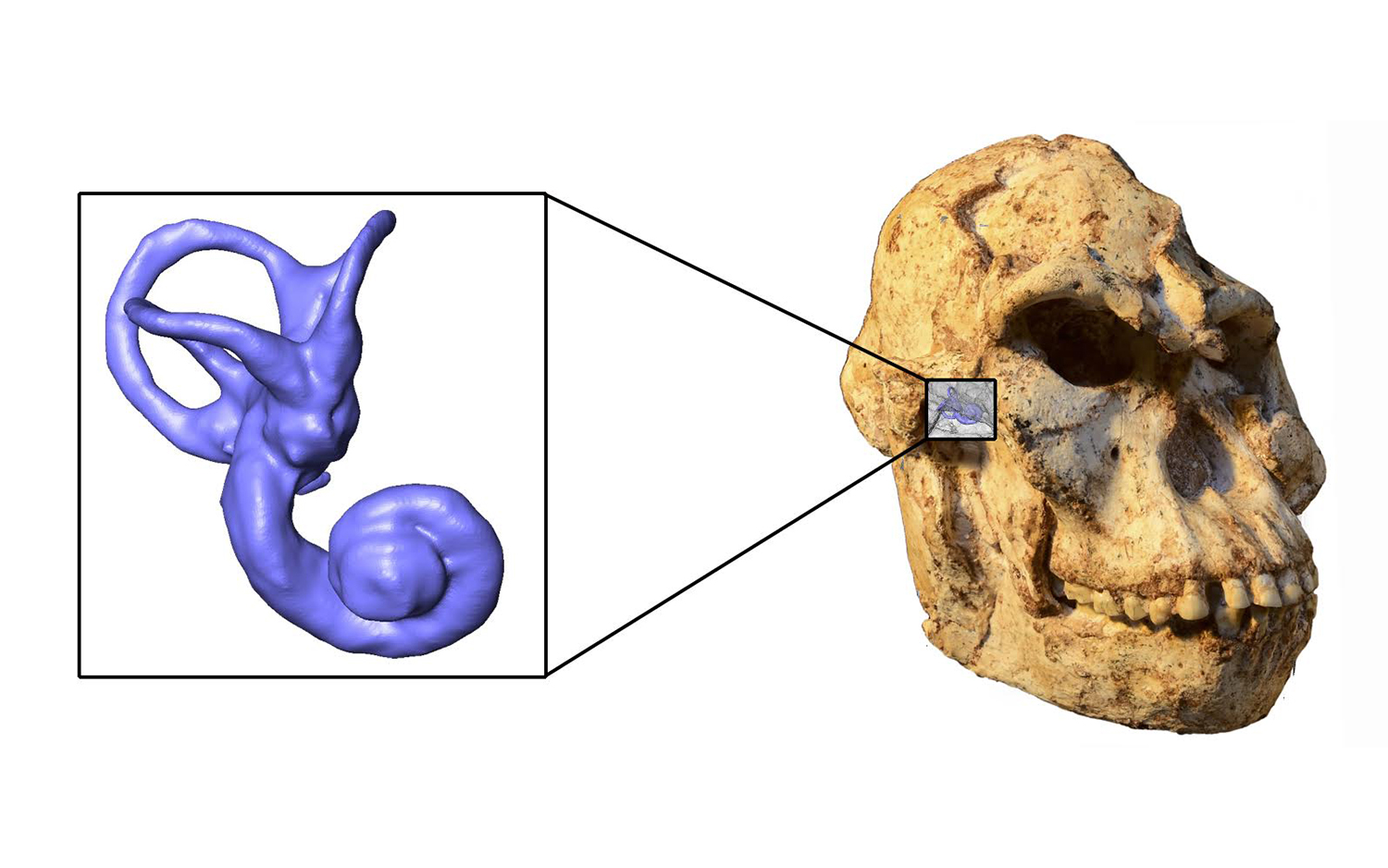

Little Foot is an exceptionally well-preserved female Australopithecus — a genus in the human family tree — dating to 3.67 million years ago. Her near-complete skeleton, discovered in a cave in South Africa in 1994, was finally excavated in December after a 20-year effort (which the scientists described as a "miracle"), and close analysis of her skull enabled scientists to create 3D models of the tiny structures in her inner ear.

This "bony labyrinth" holds important clues about balance and movement, researchers reported in a new study. In shape, Little Foot's inner-ear structure is "substantially different" from early Homo species, suggesting that she moved differently — perhaps more like our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees. [In Photos: 'Little Foot' Human Ancestor Walked With Lucy]

Because Little Foot's skeleton is so well-preserved, it presents scientists with a unique opportunity to investigate Australopithecus' bipedal locomotion. Experts have previously interpreted how early hominins moved by examining skeletal features such as the length and shape of leg bones, and the shape of the feet, pelvis and spine.

However, the shape of the inner ear, which is critical for balance, can also provide valuable information about locomotion. In humans, the inner ear evolved to facilitate "unique activities" like running, and the shape of Little Foot's inner ear offered similar insights into Australopithecus movement, lead study author Amélie Beaudet, a researcher with the School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, said in a statement.

Distinctly "ape-like"

For the study, the researchers scanned the interior of Little Foot's skull and used the data to construct 3D models of her inner ear. They then compared the models with the inner ears of 17 early hominin specimens, 10 extant humans and 10 chimpanzees.

The scientists discovered that Little Foot's ear canals differed greatly from those in human ears, and they were also very different from another hominin group known as Paranthropus, which lived at the same time as early humans. In fact, Little Foot's canals were distinctly "ape-like," resembling those of chimpanzees. This suggests that the way Australopithecus moved likely had something in common with chimps, according to the study.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Our analysis of the inner ear might be compatible with the hypothesis that Little Foot and the Australopithecus specimens in general were walking on two legs on the ground but also spent some times in the trees," Beaudet said.

The shape of Little Foot's cochlea — a hearing organ deep inside the ear that senses vibrations — also differed from that in Homo species, implying that Australopithecus interacted with their environment differently than their human cousins, the researchers reported.

"This organ is related to sound perception and to ecological factors such as diet, habitat or communication," Beaudet said in the statement. "Little Foot differed in this regard with early members of our own genus, implying some difference in behavior."

The findings were published online in the February 2019 issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

- Human Origins: Our Crazy Family Tree

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

- How Hominids Evolved (Infographic)

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.