Opal-Filled Fossils Reveal Timid, Dog-Size Dinosaur That Lived Down Under

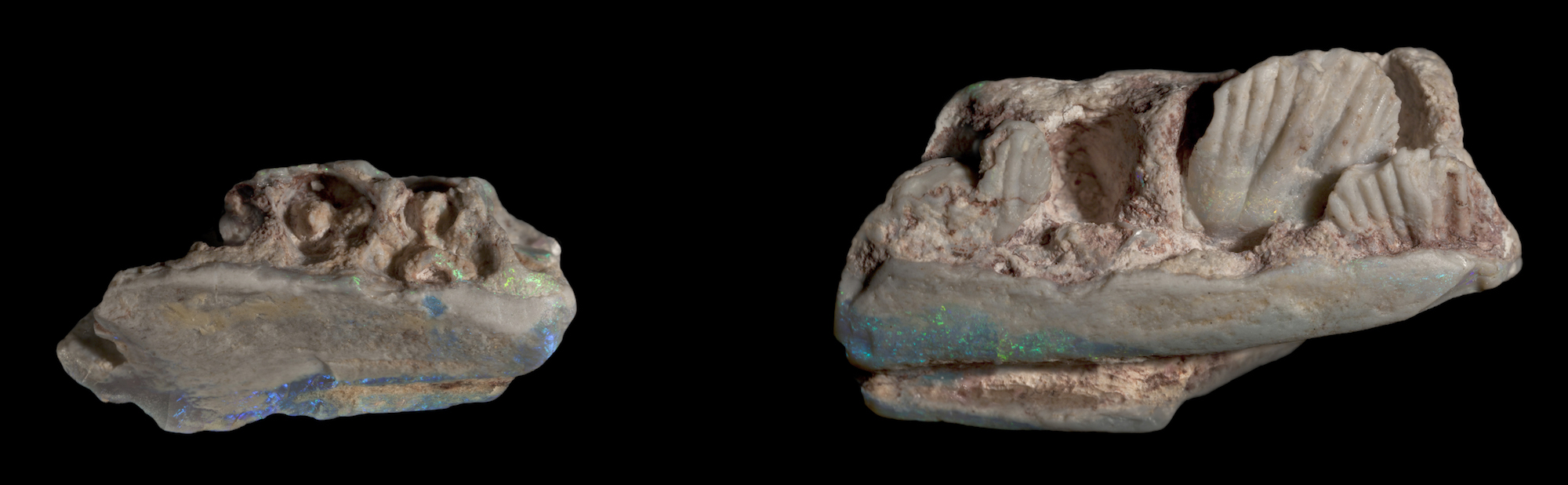

When Mike Poben, an opal buyer and and fossil fanatic, bought a bucket of opal from an Australian mine, he was surprised to find to find what looked like an ancient tooth in the pile.

Later, he also found a fossilized jaw piece — one that was shiny and glistening with opal.

After showing the two opalized specimens to paleontologists in 2014, Poben learned that they were part of a previously unknown dog-size dinosaur species, a new study finds. This dino lived about 100 million years ago in Australia, back when the landscape was lush and dotted with lakes. [Photos: Meet Wade, the Long-Necked Dinosaur from Down Under]

The fossils originally came from a mine in Wee Warra, near the town of Lightning Ridge in New South Wales. The mine's amazing name gave the paleontologists an opportunity that was too good to pass up, so they named the newfound Cretaceous-age dinosaur Weewarrasaurus pobeni.

"Weewarrasaurus was a gentle herbivore about the size of a kelpie dog [a type of Australian herding dog]," said study lead researcher Phil Bell, a senior lecturer of paleontology at the University of New England in Australia. "They got around on two legs and had a long tail used for balance. Because they were small and didn't have horns or particularly sharp claws for defense, they were probably quite timid and would have traveled in small herds or family units for protection."

In that sense, these dinosaurs were likely the kangaroos of Cretaceous Australia, Bell told Live Science. "I think I would have liked one as a pet."

The finding is remarkable, and not just because Poben happened across the fossils in an opal-filled bucket. It's extremely rare to find opalized fossils in general, though "Lightning Ridge is the only place in the world where you find opalized dinosaurs," Bell said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During the Cretaceous, Lightning Ridge was a flood plain where dinosaurs lived, Bell said. Most of the opalized fossils found there came from marine creatures that lived in a nearby ancient sea. These iridescent fossils include shells, cephalopods known as belemnites and marine reptiles called plesiosaurs.

But sometimes, an opalized dinosaur is also uncovered.

"Occasionally, a bone from a land animal, like a dinosaur, would wash out to sea" and fossilize, Bell said. There, they may encounter silica minerals in the water, the solution that makes opal. Sometimes when these bones fossilized into rock, these minerals would accumulate in in the fossils' cavities, laying down opal. Other times, if the organic bone was still present, these silica minerals could take its shape, preserving its internal structure as opal, according to Geology In, a news site focused on Earth sciences.

Unfortunately, the rest of W. pobeni, at least this particular specimen, is likely lost and gone forever.

"Because these things are exhumed by opal miners, lots of other information is often lost, like their exact position in the mine and any other fossils that were found around it," Bell said. "We know of plenty of cases where a miner has brought up a handful of bones from a single animal. The rest of the thing might have been destroyed in the mining process or sitting in a waste pile at the bottom of the mine."

Poben has since donated the fossils to the Australian Opal Centre, a museum that holds the world's largest collection of opalized fossils, according to National Geographic.

The study was published online in December in the journal PeerJ.

- Images: Denali National Park's Amazing Dinosaur Tracks

- Photos: New Triceratops Cousin Unearthed

- Photos of Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.