Lionfish: Beautiful and Dangerous Invaders

Turkeyfish. Butterfly cod. Feather fins. A lionfish (Pterois) by any other name looks just as lovely. Adorned in bold maroon, brown and white stripes, lionfish drift through the water by gently waving their fan-like fins. Floating tentacles frame their faces, making lionfish appear soft and delicate. But beware! These mysterious beauties come armed with venomous spines, and they are invading tropical waters around the world.

Fast fishy facts

Lionfish hail from the South Pacific and Indian oceans, their habitat stretching from Australia up to Japan and South Korea. Twelve different lionfish species swim through this region, feasting on shrimp and smaller fish. Lionfish corner their prey against reefs and rocks, then strike suddenly to swallow the prey whole. A voracious species, lionfishes' stomachs can expand to up to 30 times their normal size after a meal, according to Smithsonian magazine, leaving the fish plenty of room for seconds.

Lionfish not only have huge appetites, but also breed with similar gusto. They reproduce year-round, meaning a mature female can release about 2 million eggs per year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Juveniles measure less than an inch (2.5 centimeters) long and grow to about 13 to 15 inches (33 to 38 cm) long as adults. Unusually large lionfish have been found swimming at depths of up to 300 feet (91 meters), and these mega-specimens breed and eat even more than their smaller counterparts do. Lionfish can survive for up to 15 years in the wild, according to National Geographic.

No matter the size, all lionfish sport spines along their back, pelvis and underside, and they use these protrusions for defense. According to National Geographic Young Explorer Erin Spencer, when a lionfish spine punctures flesh, the pressure pushes out toxin from two venom glands along the fish's backbone. The poison rushes through channels on either side of the backbone, through the spine and into the victim.

A painful sting

In humans, lionfish stings cause intense pain and sweating, and in extreme cases, respiratory distress and paralysis. The intensity and duration of these effects depend on an individual's sensitivity to the toxin and how many spines have stabbed them. The only known remedy is to remove the spines and soak the wound in hot water, no hotter than 114 degrees Fahrenheit (45.6 degrees Celsius), which helps break down the toxin, according to Medscape. The pain usually subsides after one or two days but can sometimes persist for weeks.

Few studies have investigated what makes lionfish stings so painful. Some toxins act nonspecifically and punch pores through cell membranes indiscriminately. However, a 2018 study published in the journal Pain suggested that lionfish venom specifically targets nerve cells that relay pain signals throughout the body.

"You can apply lionfish venom to a dish of cells isolated from the dorsal root ganglia [a cluster of sensory nerve cells in the spinal cord], and they act on a subset of those cells that are specifically responsible for sensing pain," said Stephanie Mouchbahani-Constance, first author of the study and a graduate student at McGill University in Montreal. "It shows the venom has evolved just to cause pain — it doesn't want to kill, it doesn't want to paralyze."

Mouchbahani-Constance said that future research will explore how the venom works on a molecular level and how predators of the lionfish consume the species safely. Further research into how lionfish venom causes pain could lead to the development of an antidote, she said.

Lionfish invasion

Though known for their venom and flowing fins, lionfish have also earned notoriety as an aggressively invasive species. Far from the Indo-Pacific region, lionfish now abound in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coast of the Eastern U.S., from Florida to North Carolina. The invasion was initiated off the coast of South Florida in 1985, where lionfish were likely released after being purchased as aquarium fish, according to NOAA. By the early 2000s, the Eastern Seaboard teemed with lionfish fins.

But the spread didn't stop there; studies now suggest that the lionfish invasion has also struck the Mediterranean Sea.

Lionfish have no natural predators beyond the Indo-Pacific, so invasive populations swell unchecked by nature. Not even sharks go after the ornate invaders.

Meanwhile, lionfish gobble down native fish species at alarming rates. In the Bahamas, lionfish decimated about 65 to 95 percent of the endemic small-reef fish in just 30 years, according to Oceana. Thanks to their prolific feeding and breeding, lionfish appear in densities of over 350 fish per hectare on some reefs, according to a 2009 report.

Since invasive lionfish lack predators, humans have stepped in to curb their spread. Scientists want to deplete lionfish populations so that native fish species can recover. Research suggests that lionfish are eating up rare fish before humans even discover them.

In addition to eating ecologically important fish, lionfish chow down on commercial species that might otherwise be destined for someone's dinner table. Professional fishers, too, have a huge stake in this game.

Fighting the flood

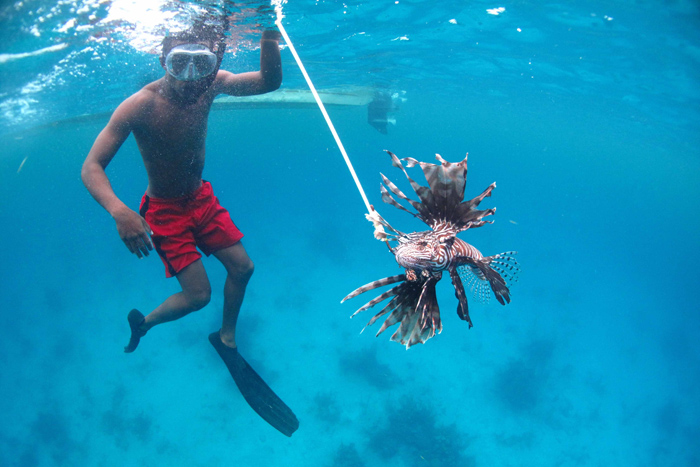

Organizations hold fishing competitions called derbies to rapidly purge many lionfish from an area. At these competitions, participants win prizes for catching the most, biggest or smallest lionfish in the designated time. Divers can pull in thousands of lionfish in just one day, and research suggests that these efforts pay off. Thinning the lionfish populations consistently from specific locations is enough to boost native fish populations.

But many lionfish live beyond the reach of spear fishers. A 2017 study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science suggested that lionfish flourish in depths below conventional diving limits, growing larger and reproducing at higher rates than fish that dwell in the shallows. These deep-water fish flee from humans on sight, suggesting that the animals spend part of their lives at shallower depths and learn to avoid capture.

To reach these deep-dwelling lionfish, the company iRobot designed a diving robot armed with a lethal shock. Other scientists are developing deep-sea drones, modified lobster traps and traps that lure lionfish in with tantalizing sounds, according to WFSU News in Florida. As the lionfish invasion persists, efforts to stymie it will have to get more and more creative.

If you can't beat 'em, eat 'em!

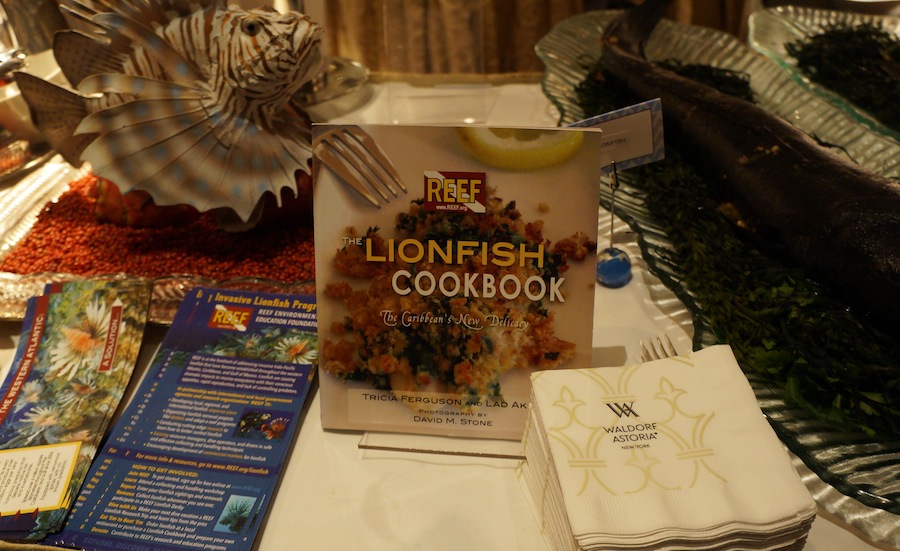

Lionfish are venomous, not poisonous, which means they deliver their toxin through needles, namely their spines. Toxin from poisonous creatures, on the other hand, must be ingested to work its magic. Without their spines, lionfish have no way to inject venom. This trait means that people can safely catch, cook and consume lionfish as long as they avoid the offending spines.

With hopes of encouraging seafood lovers to help curb the lionfish population by eating them, NOAA launched its "Eat Lionfish" campaign and Reef Environmental Education Foundation released a lionfish cookbook. Cooking a lionfish breaks down the toxins housed along its spine, leaving nothing except delicate, flaky flesh.

Conservation groups hope to generate a transient market for lionfish — that is, one that will eradicative the invader without generating long-term demand. Some invasive species experts doubt that this culinary control strategy will work, as it's been employed against other species in the past and failed, according to VOA News. However, a number of restaurants have caught on to the trend.

Additional resources:

- List of restaurants that serve lionfish in Florida, from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

- More on lionfish, from the CABI Invasive Species Compendium.

- Upcoming lionfish culling events, from the Reef Environmental Education Foundation.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.