The Polar Vortex Is Collapsing — Here's What That Means for Your Winter Weather

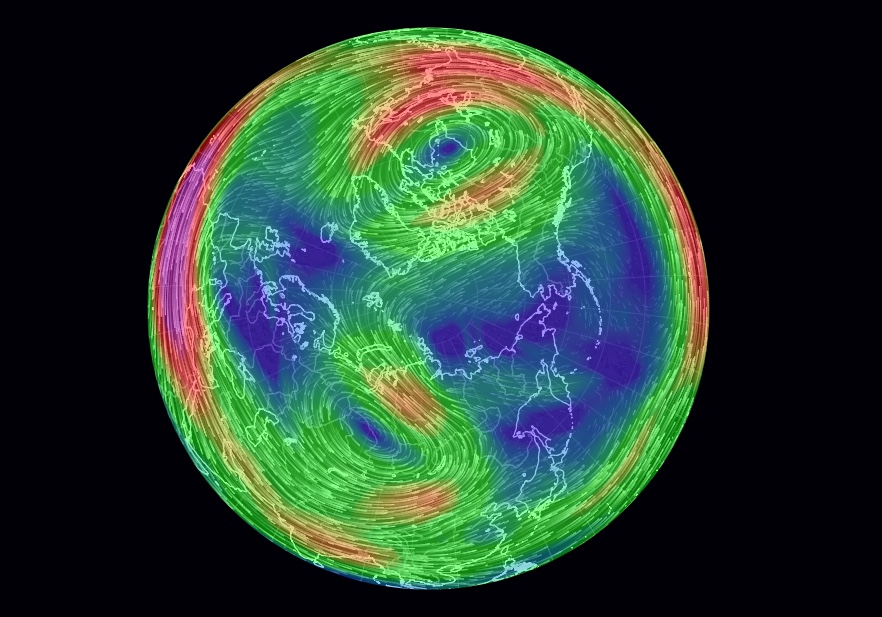

The blast of Arctic weather headed for the United States this weekend could be a first sign of still worse things to come this winter, with signs that a circular low-pressure system of swirling winds that normally keeps frigid air locked up at the North Pole has been disrupted and split into smaller parts.

The disruption in this counterclockwise-spinning beast, called the polar vortex, is thought to be caused in part by a warm summer over the Arctic and a relatively cold fall over Siberia. The result for the United States and northern Europe? A severe winter lasting throughout February and possibly into March.

Meteorologist Judah Cohen agreed that the breaking up of the polar vortex could be the culprit for the coming storm. Cohen, the director of seasonal forecasting for the weather risk management company Atmospheric and Environmental Research (AER), based in Lexington, Massachusetts, told Live Science that the coming snowstorms in the United States this weekend are consistent with weather models that predicted severe wintry weather to come in the coming weeks. [Infographic: Earth's Atmosphere Top to Bottom]

The weather models suggested that the disruptions would follow the pattern of polar vortex disruptions seen during the northern winter last year, which resulted in freezing weather across the United States in December and January, and a severe cold snap in March over the United Kingdom.

"This pattern looks much more active, [with] more winter type storms and Arctic outbreaks — I think I would attribute it to definitely being a polar vortex disruption, because it is very consistent with what we've seen in the past," Cohen said.

Polar winds

The northern polar vortex is a fast-flowing stream of air that circles the North Pole in the upper parts of the atmosphere, known as the stratosphere, about 20 miles (32 kilometers) above the surface.

A similar polar vortex exists over the South Pole, but it is the northern polar vortex that can bring severe winter weather to the United States and Europe.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

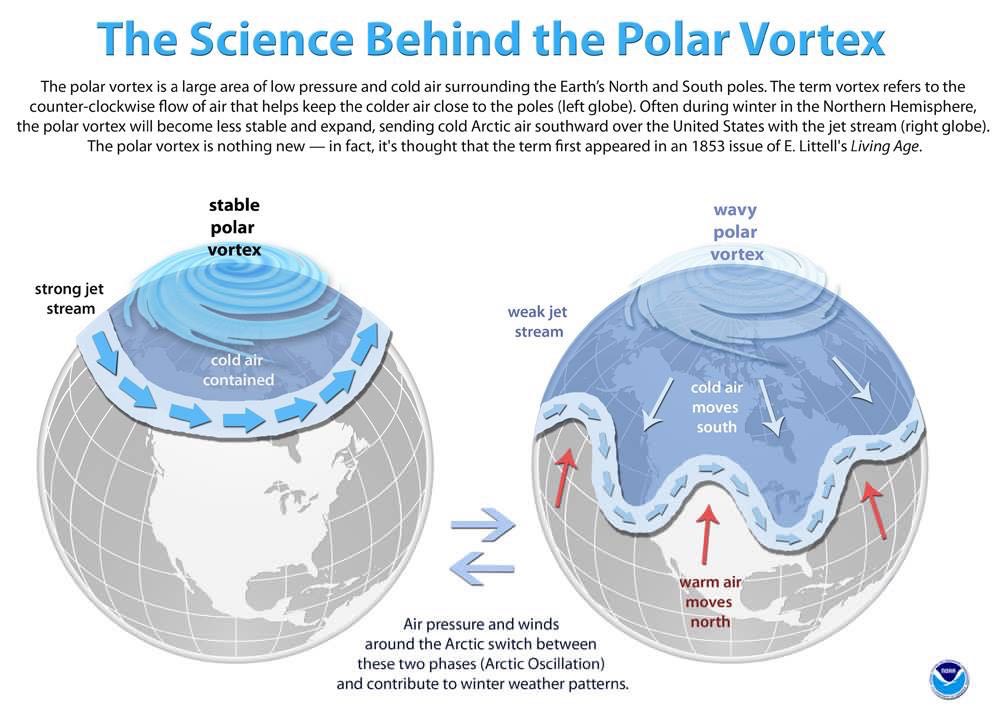

When the northern polar vortex is strong, Cohen explained, it keeps most of the air cooled by the Arctic in the polar region, resulting in mild winter temperatures in the middle latitudes of the eastern United States, and in northern Europe and Asia.

But when the polar vortex weakens, the once-trapped cold air can meander throughout the top of the Northern Hemisphere, bringing polar temperatures and extreme winter weather to lower latitudes, he said.

"Think of the polar vortex as a spinning top, and where the polar vortex goes so goes the cold air," Cohen said. "A strong polar vortex is a fast, tightly spinning top centered over the North Pole, keeping all the cold air with it close by over the Arctic. [But] a weak or perturbed polar vortex is a spinning top that has been banged or bumped into an object multiple times … the top slows down and wobbles and can meander from its location."

As for what knocked into this spinning top, Cohen points, in part, to summer warming in the Arctic region and a relatively cold fall in Siberia.

"I have argued that Arctic change has certainly been a contributor," he said. "The loss of sea ice, especially in the Barents and Kara seas, which are near Scandinavia in north-west Russia … and also an increasing trend in Siberian snow cover in October, I think that has also been contributing.

Winter weather

In recent days, weather scientists have seen the northern polar vortex split into three smaller parts, which have now changed into two giant patches of polar winds in the stratosphere — one over northern Canada and one over central Russia.

Snowstorms have been forecast today (Jan. 18) and tomorrow (Jan. 19) for the central Plains and Midwest of the United States, as part of what's being called winter storm Harper; and the winter weather is expected to hit the mid-Atlantic and Northeast of the United States later in the weekend.

Cohen said these patterns followed the weather patterns seen last winter, which was exceptionally cold in the United States over the New Year and the first weeks of 2018.

But he warned that a cold snap isn't a foregone conclusion; the winter weather could still turn out to be relatively mild if the polar vortex returns to its normal configuration in the coming weeks.

"Right now, the weather looks like it is very consistent with our expectations of how the weather would transition following these type of events, but we'll see," he said. "These [weather patterns] tend to be episodic, so it doesn't come all down once … not every day will be below normal, and we will not have snow every day."

Cohen added, "[But] I think at least through the end of February, and I would think probably into early March, there will be kind of a skewing of the probabilities or the frequency of severe winter weather."

- On Ice: Stunning Images of Canadian Arctic

- The 10 Worst Blizzards in US History

- Image Gallery: Life at the North Pole

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.