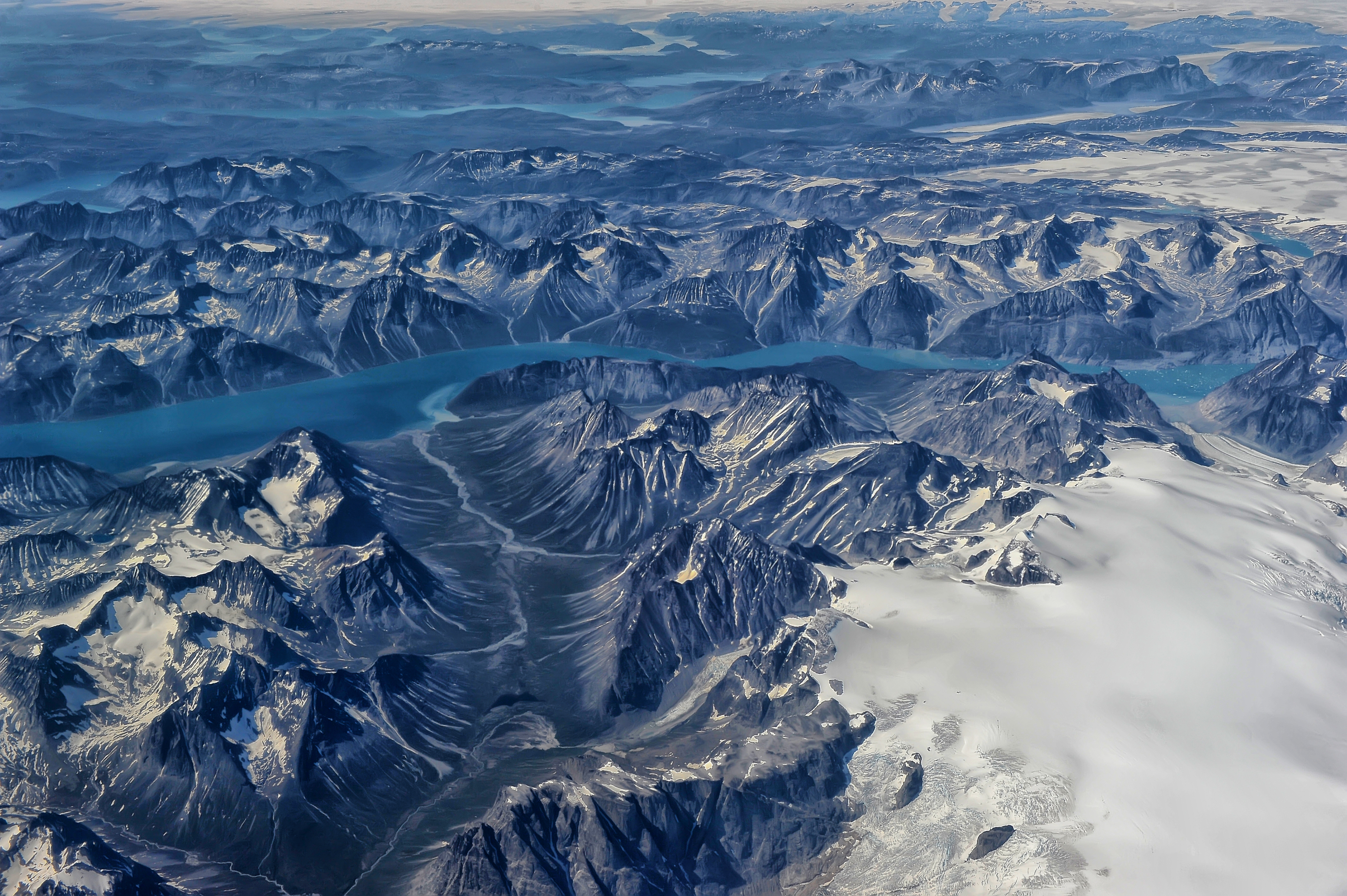

The Greenland Ice Sheet Is Melting at Astonishing Rate

Last week, a cauldron of concerning news articles made two things very clear: The ocean is warming and Antarctica's ice is melting.

Now, a new study shows how much global warming is pounding another area: Greenland.

Greenland's ice sheet is not only melting, but it's melting faster than ever because the area has become more sensitive to natural climate fluctuations, particularly an atmospheric cycle, a group of scientists reported today (Jan. 21) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers found that the ice is vanishing four times faster than it was in 2003 — and a good chunk of that acceleration is happening in southwest Greenland.

This area was previously not considered at as much risk of melting because it doesn't host large glaciers like the southeast and northwest regions do. While glaciers are smaller rivers of ice that creep across the landscape and can break apart and melt from warm ocean water, the actual gigantic ice sheet was thought to be more resistant to that kind of melt. [Images of Melt: Earth’s Vanishing Ice]

But since the southwest part of the ice sheet is devoid of glaciers, the melting must be happening via another mechanism: A warmer atmosphere would melt the ice more inland, and the resulting water would run off into the ocean.

"In terms of rate of transfer of ice to oceans, both mechanisms are important," said lead author Michael Bevis, a geophysicist at The Ohio State University. But the fact that the ice is melting faster and faster, even inland, and running out as a river of water, "that's a surprise," he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bevis and his team hypothesize that Greenland's melting is accelerating so much because the effects of a natural atmospheric circulation cycle, called the North Atlantic Oscillation, are being amplified by the broader warming that the planet is facing. Here's how it works: When the North Atlantic Oscillation is in what scientists call a "positive" phase, the skies above Greenland tend to be cloudy, and thus don't encourage melting, Bevis said. But when it's in a "negative" phase, warm air gets pulled from the south all along the west of Greenland, leading to blue, clear skies that allow more sunlight to reach the ice and cause more melting.

These oscillations have been happening for thousands of years and before recently, they didn't have a large impact on Greenland's ice: The ice would melt when the cycle was negative and form again when it was positive. "But suddenly, because of this global warming, this relatively small fluctuation can push you over the top [and cause] a degree of melting we haven't seen before."

What's more, if the atmosphere continues to warm, this degree of melting will start to happen on its own, without the help of the cycle, he added. Though glaciers are still the major contributor to sea-level rise, the researchers predict that at the rate that it's increasing, melting in southwest Greenland will become a major player in the future.

The sensitivity of Greenland's ice sheet to a warming atmosphere (due to global warming) can perhaps be viewed as a "ray of hope," said Luke Trusel, a professor in the department of geology at Rowan University who was not part of the study. The sensitivity "means that we, as humans, can control how rapidly the ice sheet changes in the future," he added, referring to the idea that humanity can reduce greenhouse gas emissions that ultimately warm the atmosphere.

Trusel and his team had published a similar paper in December in the journal Nature that found the Greenland ice sheet to be more sensitive to global warming than it has been even a few decades ago and that Greenland's melting and runoff are the highest they've been in centuries.

"By limiting greenhouse gas emissions we will limit warming, and thus also limit how rapidly and intensely Greenland affects our coastal communities through sea level rise," Trusel said.

- Ancient Ice And Our Planet's Future

- 8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World

- Earth in the Balance: 7 Crucial Tipping Points

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.