Ominous Cracks Form in the Northern Hemisphere's Longest Floating Glacier

A floating "tongue" of ice in one of Greenland's biggest glaciers suffered a bad break in 2012, releasing an iceberg about the size of Manhattan. Now, new cracks in the glacier hint that another sizable chunk could break away..

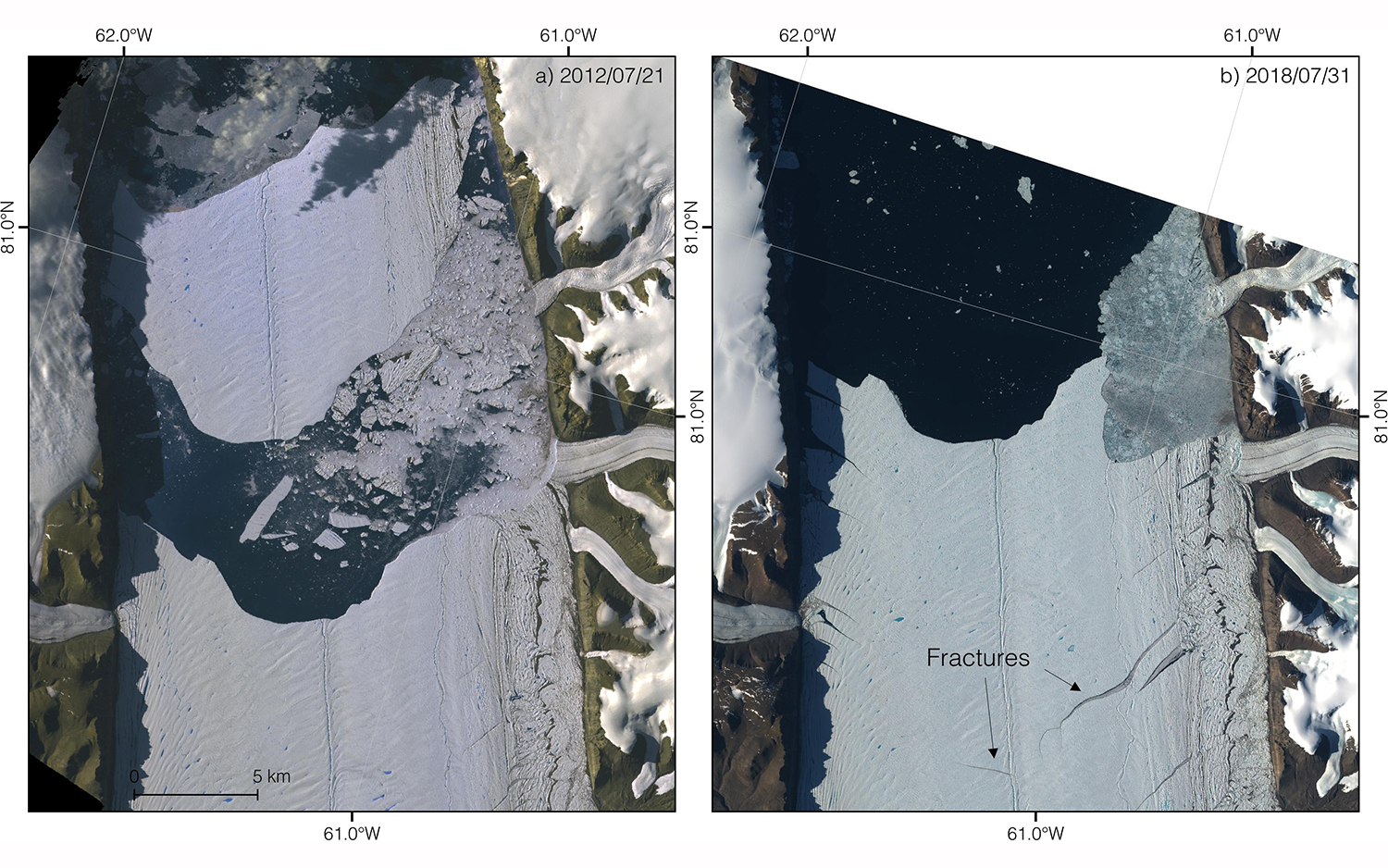

After a massive iceberg separated from Petermann Glacier in 2012, the glacier's slow but steady momentum toward the sea accelerated; since then, its flow rate has increased by an average of 10 percent, according to a new study.

Should the new cracks widen and fracture into an iceberg, the glacier's flow would likely speed up even more, leading to greater ice loss. [Photo: Giant Iceberg's Birth Snapped from Space]

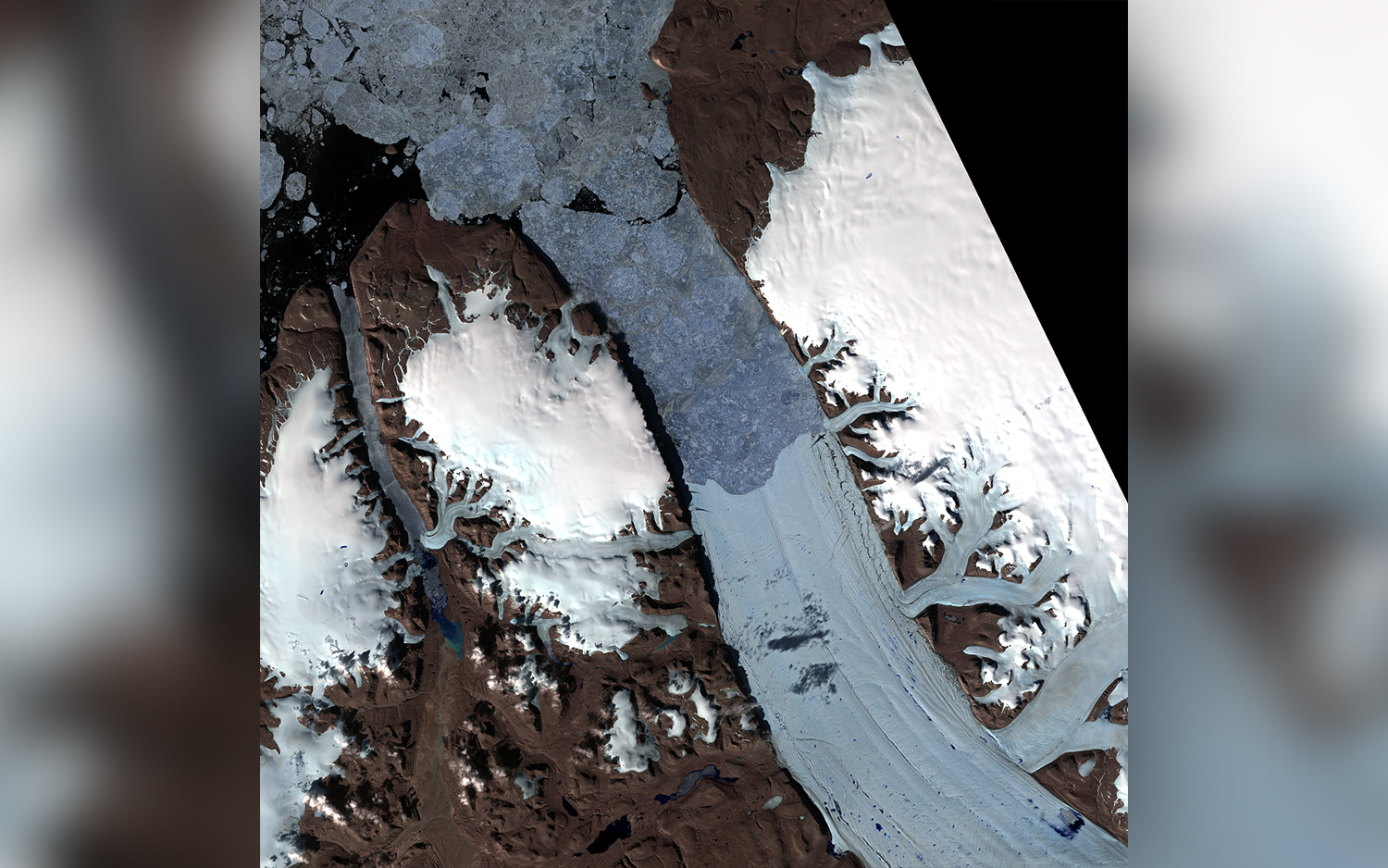

Petermann Glacier spans about 500 square miles (1,295 square kilometers) in northwestern Greenland, and it is one of only three Greenland glaciers with an icy "tongue," which lolls across the fjords and into the North Sea. Measuring 9 to 12 miles (15 to 20 km) wide and approximately 44 miles (70 km) long, Petermann's tongue is the Northern Hemisphere's longest floating glacier, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

In 2010, Petermann Glacier lost about 25 percent of its tongue in a single break. The ice island that broke off measured at least 100 square miles (260 square km) long and over 700 feet (213 meters) thick — about half the height of the Empire State Building, Live Science previously reported.

The 2010 incident didn't significantly affect the glacier's flow. However, the 2012 break was another story, producing "a detectable glacier speedup," the study authors wrote in the study. In 2016, the glacier's flow speed was about 3,000 feet (1,135 m) per year — an increase of around 10 percent from 2011, study co-author Niklas Neckel, a glaciologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven, Germany, said in a statement.

When the glacier flows to the ocean, the rock walls on either side of the long tongue act as a drag and reduce its speed. But the shorter the tongue, the less lateral pressure and friction there is holding the glacier back. This limits the braking effect "so that the glacier begins flowing faster," lead study author and AWI ice modeler Martin Rückamp said in the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now, new cracks have recently emerged in the tongue, about 8 miles (12 km) from the new edge. The computer models that demonstrated the glacier's accelerated flow after 2012 also predict that Petermann's rush toward the sea will speed up if more ice breaks off it, the researchers wrote in the study. The resulting ice loss could cause sea levels to rise.

"We can't predict when Petermann Glacier will calve again, or whether a calving event would actually calve along the cracks we identified in the ice tongue," Rückamp said. "But we can safely assume that, if it does come to a new calving event, the tongue will retreat considerably, and the rock's stabilizing effect will further decline."

The findings were published online Jan. 11 in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

- Images: Greenland's Gorgeous Glaciers

- Photos of Melt: Glaciers Before and After

- The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.