This 2.1-Billion-Year-Old Fossil May Be Evidence of Earliest Moving Life-Form

About 2.1 billion years ago, a blob-like creature inched along on an early Earth. As the organism moved, it carved out tunnels, which may be the earliest evidence of a moving critter on the planet.

Until this discovery, the earliest evidence of motility — that is, an organism's ability to move independently using its own metabolic energy — dated to about 570 million years ago, according to fossils from different locations. That's a good 1.5 billion years younger than the new finding.

Whatever left the teeny, tiny tunnels was likely a cluster of single cells that joined ranks to form a slug-like multicellular organism, the researchers said. And perhaps, this sluggy conglomerate tunneled through the mud in search of greener pastures or food to gobble up, the international team of scientists said. [In Images: The Oldest Fossils on Earth]

However, not everyone agrees that these tunnels were made by complex life, and one researcher, who was not affiliated with the study, called the claims "imprecise."

Tunneling life?

The researchers found the trace fossils in Gabon, along Africa's west coast. A trace fossil is a fossil that was not part of an organism's body that it leaves behind, such as a footprint, a burrow or even poop. In this case, the trace fossils are a series of slender tunnels that were made in what was once called the Francevillian inland sea — an oxygenated and shallow marine environment that existed during the Paleoproterozoic, an era lasting from about 2.5 billion to 1.6 billion years ago.

After collecting hundreds of specimens from the ancient inland sea, the scientists in the recent study found fossilized tunnels. These structures indicated that some ancient multicellular organisms were complex enough to scoot through the mud, said first author Abderrazak El Albani, a professor of paleobiology and geochemistry at IC2MP, an institute of the University of Poitiers and the the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in France.

There is a modern analogue to this weird slug-like creature. During times of starvation, some cellular slime molds aggregate together in what is called a "migratory slug phase," so they can look for food together, El Albani said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

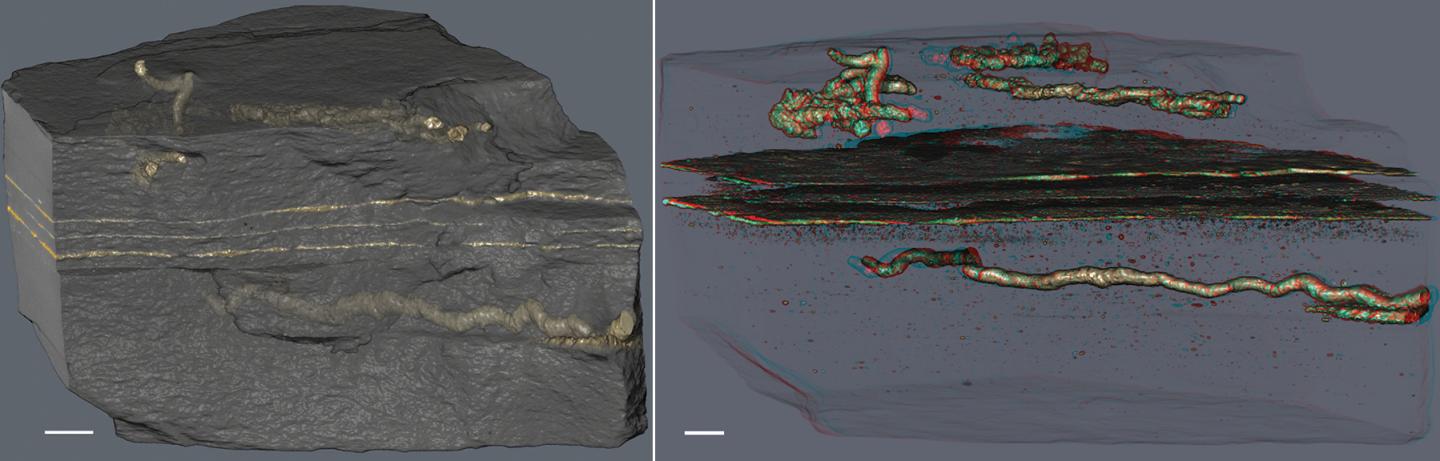

The tunnels these ancient critters left behind are small, with a diameter of up to 2.3 inches (6 centimeters) and a length of up to 6.7 inches (17 cm). What's more, the tunnels appear to be made by something that moved laterally and vertically through the muck, El Albani told Live Science. To determine for sure that these tunnels were left by living creatures, the researchers analyzed the structures in several ways. For starters, the scientists used an X-ray computed microtomography (micro-CT) scan to analyze the specimen in 3D (see the above video).

The team also analyzed the chemical components in the trace fossils, finding that these traces were biological in origin and also matched the age of the 2.1-billion-year-old sediment around them. Moreover, the tunnels were next to fossilized microbial mats, known as biofilms. Perhaps the strange, slug-like beast grazed on these microbial "carpets," the researchers said.

While much about this critter remains a mystery, its existence raises new questions about the history of life, El Abani said. Was this the first time a complex organism moved, and was movement perfected later on? Or was this creature's experiment cut short when atmospheric oxygen levels dropped drastically about 2 billion years ago, only for this kind of movement to resurface much later? [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

But not everyone thinks these tunnels represent the oldest proof of motility.

"The claim sounds really imprecise," Tanja Bosak, an associate professor of geobiology in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Live Science in an email. "Perhaps they are referring to something macroscopic moving — there are much older rocks (stromatolites) with shapes and textures that require the former presence of motile microbes."

She emphasized that while she didn't have time for an in-depth reading of the study, Bosak told Live Science, "I hope that they discuss this somewhere and tone down the splashy claims at least a little."

The study was published online yesterday (Feb. 11) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Images: Bizarre, Primordial Sea Creatures Dominated the Ediacaran Era

- In Photos: Ancient 'Baby' Animals Preserved in Ash

- Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.