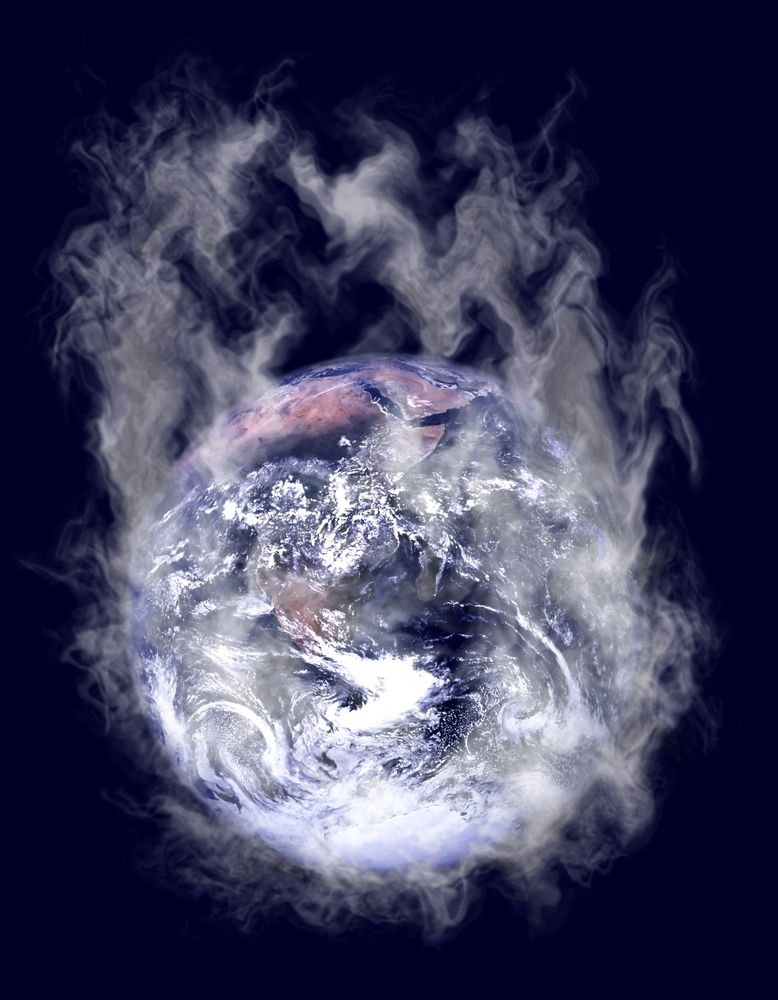

The news is dire. Ocean temperatures are at their highest since accurate measurements began in the mid-20th century. And, thanks to human-induced climate change, things are only going to get worse in the coming years.

But even if humans keep spewing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, could the oceans ever get so hot that they begin to boil? Thankfully, humanity's current practices could likely never heat up the world enough to make that happen.

"Even if we burned all known fossil-fuel reserves, we wouldn't get nearly that warm," Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at Berkeley Earth, a temperature data analysis nonprofit organization, told Live Science. "Though, it's worth mentioning that there are plenty of bad climate impacts that happen a long, long way before the surface is literally hot enough to boil water."

Greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane raise Earth's temperatures by trapping the sun's energy in the planet's atmosphere and surface — energy that would otherwise radiate away into space. About 93 percent of this extra heat gets absorbed by the surface of the ocean, Hausfather said. The heat quickly mixes through the top 330 feet (100 meters) of water, a region known as the "mixed layer," taking much longer to reach farther down, he added. But in recent years, scientists have observed rising temperatures in even the ocean's deepest realms, Live Science previously reported. [The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted]

Because water is thicker than air, it has the ability to absorb a great deal of heat. "The top 2.5 meters [8.2 feet] of the ocean holds the same amount of heat as the entire atmosphere above it," Hausfather said.

So, it's theoretically possible that Earth's oceans could get hot enough to start boiling. Warm water molecules vaporize from the ocean's surface all the time. Water vapor is itself a greenhouse gas, so greater amounts of water in the atmosphere will create a vicious feedback cycle — and a hotter world overall. Something similar is thought to have happened on Venus long ago, Hausfather pointed out, causing our sister planet's oceans to boil away. But because Earth is farther from the sun than Venus is, it would take a great deal more greenhouse gas for our planet to reach that dismal point, he said.

A 2013 paper in the journal Nature Geoscience suggested that, to induce this "runaway greenhouse" effect, Earth would need an amount of carbon dioxide that's about 10 times greater than what could be released from burning all known coal, oil and gas reserves. While this type of analysis has many caveats and uncertainties, Hausfather said, historically, our planet's oceans have been fairly resilient when it comes to climate extremes. For instance, hundreds of millions of years ago, our world experienced a “snowball Earth” scenario during which the entire surface was covered in ice, while around 55 million years ago, global temperatures were an average of 9 to 14 degrees Fahrenheit (5 to 8 degrees Celsius) hotter during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), but each time relatively stable temperatures returned, said Hausfather.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dying sun, dying Earth

But humanity is not the only thing that could possibly do in the oceans. One day, in the far future, the sun will reach the end of its life and begin to expand outward as a giant red star, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com. Over the course of the next 7 billion years, Earth's temperature will slowly rise, astronomer Robert Smith, an emeritus reader at the U.K.'s University of Sussex, told Live Science in an email.

In 2008, Smith, along with his colleague Klaus-Peter Schroeder of the University of Guanajuato in Mexico, performed calculations to figure out how Earth would meet its maker. But exactly when the oceans would begin to boil was hard to pin down, Smith said. Instead, this ocean vaporization could happen around 1 billion years from now, but added that there is a great deal of uncertainty in that figure, Smith added.

At that point, humanity might have stopped adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere and may have long gone the way of the dodos. But even once the oceans are done for, that doesn't mean life will disappear immediately.

"It's perfectly possible that some simple life-forms might survive for a while without water, but in due course (and don't ask me exactly what that means!) the surface is likely to become molten, which would almost certainly remove the last traces of life," Smith said.

- Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

- Top 9 Ways the World Could End

- Big Bang to Civilization: 10 Amazing Origin Events

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.