480-Million-Year-Old Mystery Creature Finally Identified from Its Preserved Guts

For the past 150 years, scientists have hotly debated a mysterious creature that lived hundreds of millions of years ago. And now, with the discovery of stunningly detailed fossils in Morocco, paleontologists have finally ID'd the bizarre life-forms.

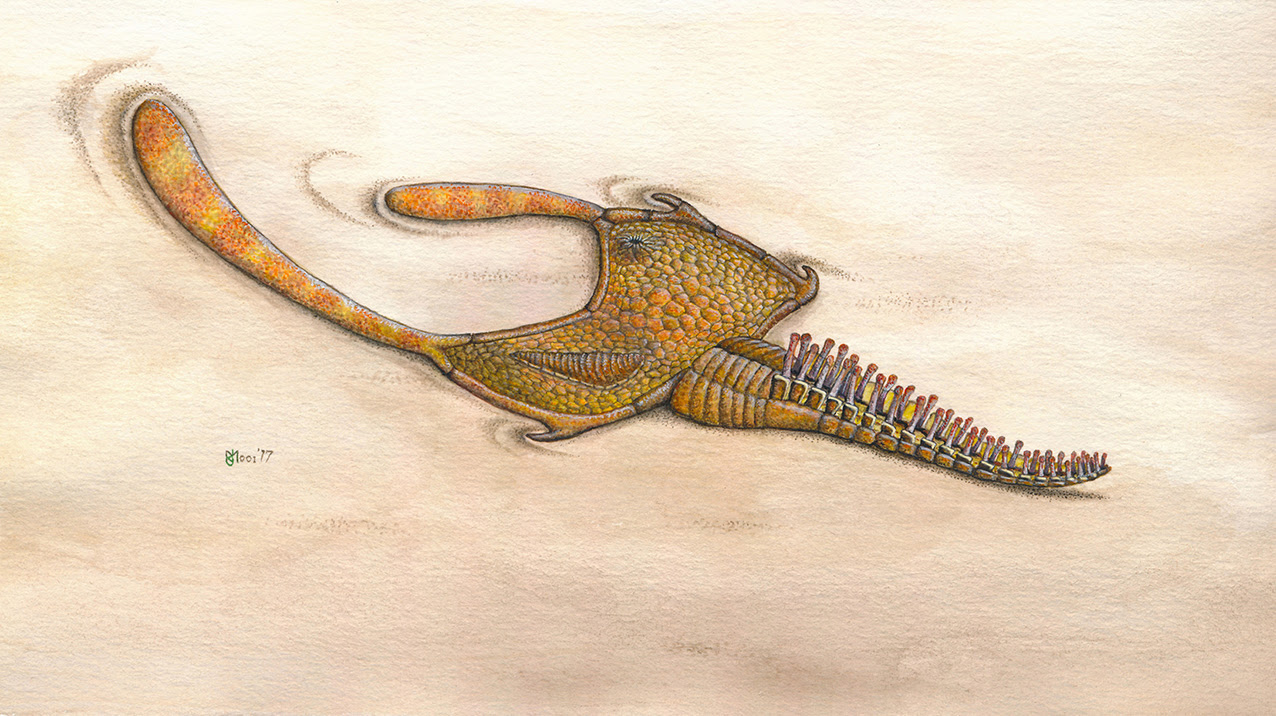

The creatures, known as stylophorans, looked like flattened and armored wall decorations that had a long arm poking off their sides. But while it was previously unclear where they fit in the animal family tree, the new study revealed that they are echinoderms, the ancient relatives of modern animals such as sea urchins, starfish, brittle stars, sea lilies, feather stars and sea cucumbers.

The finding was made possible thanks to fossils with "unequivocal evidence for exceptionally preserved soft parts, both in the appendage and in the body of stylophorans," said study lead researcher Bertrand Lefebvre, a National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) researcher at the Laboratory of Geology of Lyon in France. [Photos: Trove of Marine Fossils Discovered in Morocco]

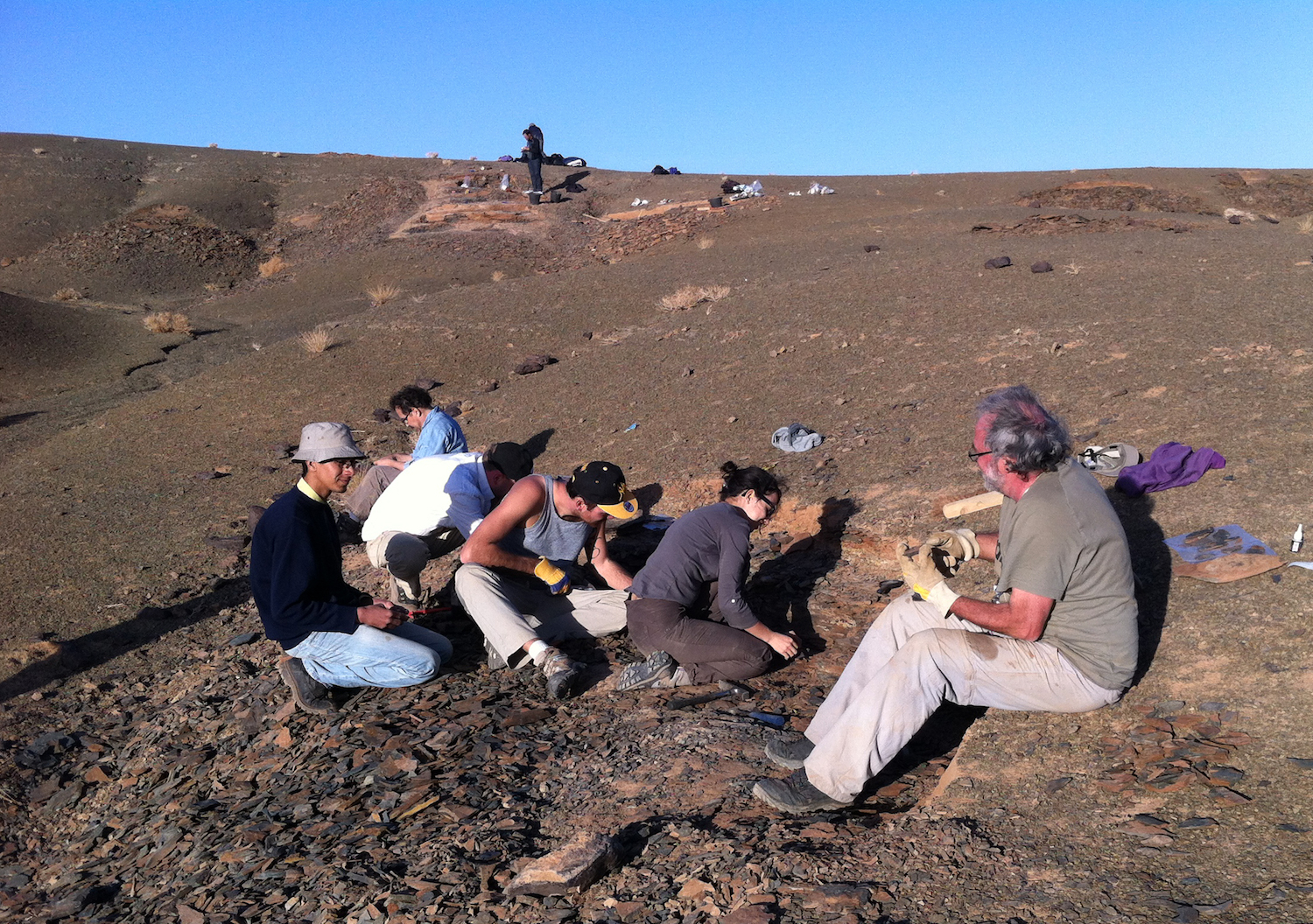

The incredible fossils were unearthed during an excavation in 2014 at the Fezouata Formation, located along the edge of the Sahara Desert in southern Morocco. The excavation yielded a bounty of fossils, including about 450 stylophoran specimens, each dating to about 478 million years ago.

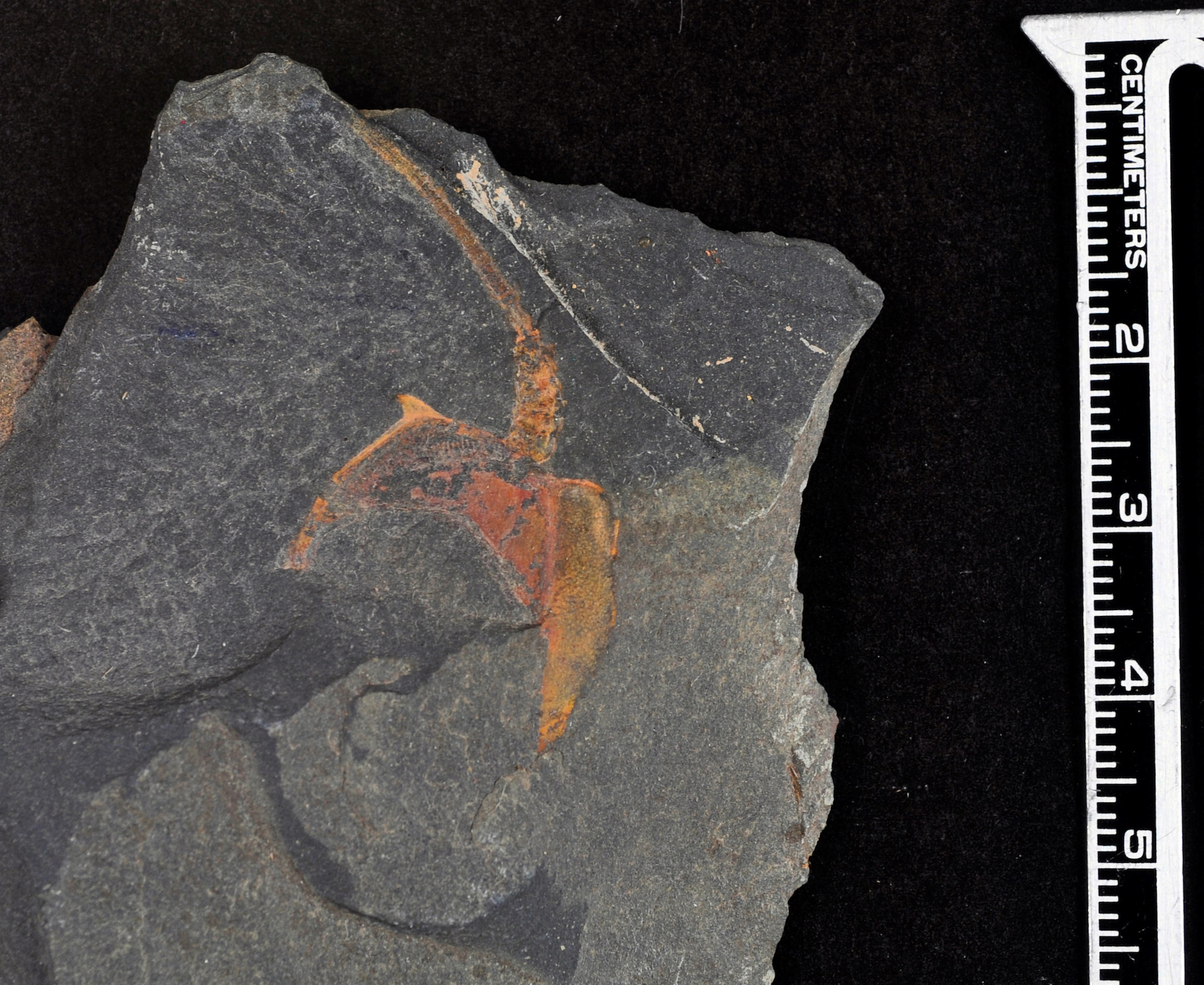

But the researchers didn't immediately realize that some of the fossils included preserved soft tissues. "It is only when we unpacked and looked at them under the binocular [microscope], back in the laboratory in Lyon, that we could see the soft parts," Lefebvre told Live Science in an email. "Their presence and identification were then confirmed by SEM (scanning electron microscope) observations and analyses."

The soft tissue finding was unprecedented. Stylophoran fossils have been found worldwide since the 1850s, allowing researchers to determine that these creatures lived from the middle Cambrian to the late Carboniferous periods, or about 510 million to 310 million years ago, when the creatures went extinct. But because soft tissues so rarely fossilize, the stylophorans were known only from their hard skeletal parts and not their squishy innards.

"Their internal anatomy was not only entirely unknown, but also — and mostly — highly controversial," Lefebvre said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What did they look like?

Stylophorans had two main parts: a core body and a weird appendage attached to it. Both the core body and the appendage were small, each about 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) long, Lefebvre said.

Previously, other researchers came up with all kinds of ideas about stylophorans.

From the 1850s to 1950s, most researchers thought that stylophorans were "normal" echinoderms. Their weird appendage was interpreted as the equivalent to the stem of sea lilies.

Normal echinoderms have internal skeletons made of mineralized, calcitic plates (although this is extremely reduced in sea cucumbers) and so-called water vascular systems that help them move and breathe, said Peter Van Roy, a paleobiologist at Ghent University in Belgium, who was not involved with the study.

Most echinoderms, including starfish, have a five-rayed symmetry. They're closely related to another invertebrate group, the acorn worms, and to vertebrates (animals with backbones). Together, echinoderms, acorn worms and vertebrates make up an overarching group known as deuterostomia, Van Roy said. [Deep-Sea Creepy-Crawlies: Images of Acorn Worms]

Then, in the early 1960s, Belgian paleontologist Georges Ubaghs noticed that the appendage was different from a stem but similar to a feeding arm, as seen in modern starfish.

In the late 1960s, British paleontologist Richard Jefferies proposed an entirely different idea. He thought that the stylophoran main body was a head (holding a pharynx and brain) and that the appendage housed muscles and a notochord (a type of primitive backbone). Jefferies thought that stylophorans were the "missing link" between echinoderms and chordates (a group that includes vertebrates).

In the 2000s, British paleontologist Andrew Smith suggested yet another interpretation. He said that stylophorans were probably not the "missing link" between echinoderms and vertebrates but were more likely primitive deuterostomes, filling the gap between acorn worms and echinoderms.

The new discovery of the fossilized soft tissue, however, has changed everything. Researchers could test, for the first time, whether the soft tissue matched what you would expect from any of these different scenarios, Lefebvre said.

Hard evidence

The newfound fossils align most closely with Ubaghs' interpretation. The stylophorans' flat bodies contained intestines, and the appendage was not closed off as a stem would be and rather looked like a starfish arm. This arm contained a water vascular system that would have helped the creatures move and eat, just like the arms of starfish do, Van Roy said.

Because stylophorans don't have five-rayed symmetry, they likely lost it, meaning they were more "advanced" evolutionarily than other five-rayed echinoderms, Van Roy added.

"This discovery is of particular importance, because it brings to an end a 150-year-old debate about the position of these bizarre-looking fossils in the tree of life," Lefebvre said.

The study is "very thorough," Van Roy said, "and I have no reservations about any of the methods used or conclusions drawn." Moreover, it highlights the importance of the well-preserved fossils of the Fezouata Formation, a place where Van Roy has previously found spectacular specimens.

The study was published online in the February issue of the journal Geobios.

- Images: Morocco's Rugged Beauty

- Photos: 'Hat'-Wearing Ancient Slug May Explain Mollusk Family Tree

- Photos: 'Naked' Ancient Worm Hunted with Spiny Arms

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.