21 Totally Sweet Spider Superlatives

Super spiders

Spiders are incredibly diverse creatures. They can be the size of the period at the end of the sentence… or the size of your face. They can live in deserts, in the tropics, in Siberia and even underwater. They can be docile or deadly, ground-dwelling or web-spinning.

To highlight the incredible accomplishments of arachnids, biologist Stefano Mammola of the University of Turin and his colleagues rounded up 99 of their most mind-boggling records in a publication in the open-access journal PeerJ. It's a wide-ranging list, but we've picked 21 of our favorite entries and paired them with pictures of the spiders that deserve a little bit of recognition. These records might just make you see arachnids in a whole new light.

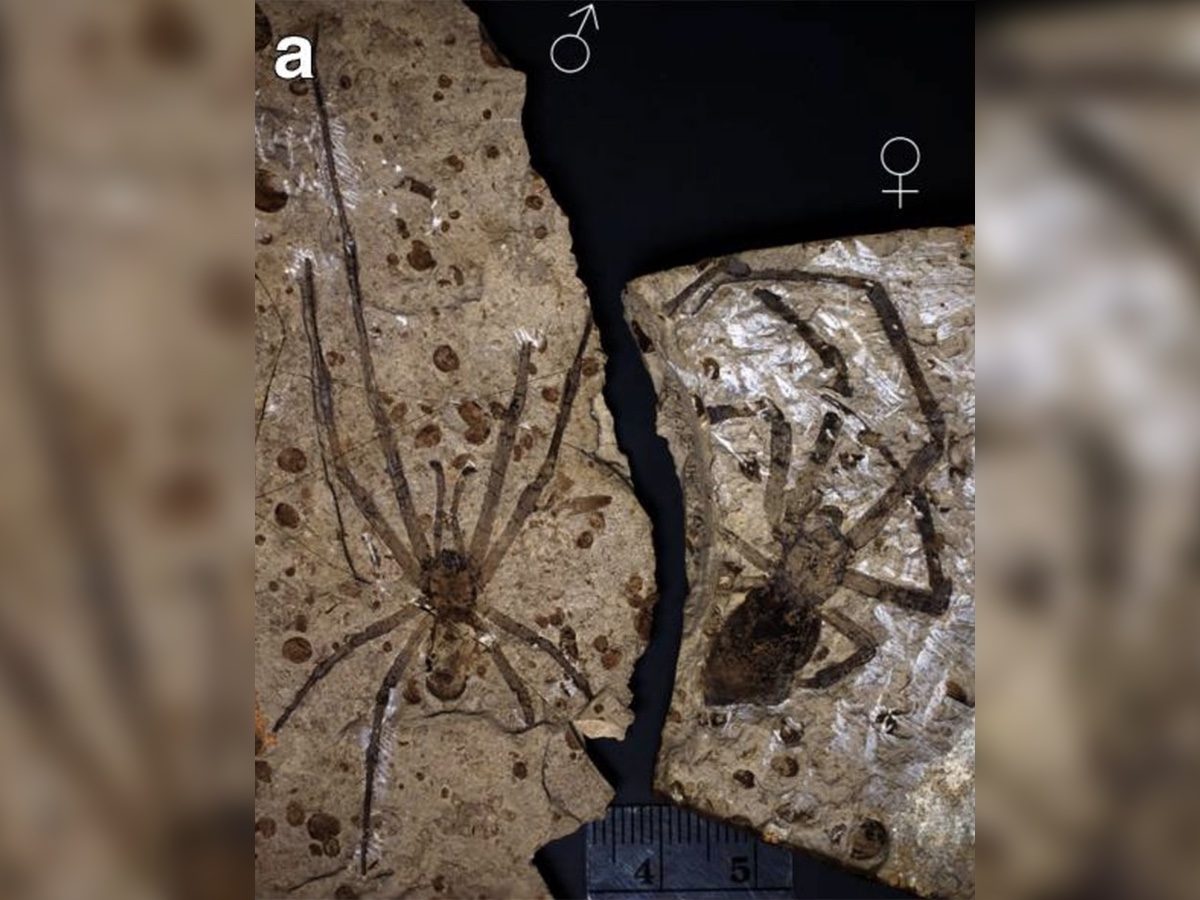

Largest fossil spider

Now here's a new twist on Jurassic Park: The largest fossil spider ever found comes from the middle of that era, some 163 million to 174 million years ago.

The species is Mongolarachnidae jurassica. Found fossilized in Inner Mongolia, China, this species had a body length of 0.7 inches (1.65 centimeters) and legs up to 2.4 inches (6 cm) long.

Oldest fossil spider

Spiders are eight-legged old souls. These arachnids have witnessed the breakup of Pangaea, the rise and fall of the dinosaurs, and the expansion and retreat of the polar ice caps. The oldest fossilized spiders date back around 300 million years, with the trophy for oldest going to a species called Palaeothele montceauensis. Discovered in Montceau-les-Mines, France, the fossil shows an impression of a spider about 0.5 inches (1.2 centimeters) long.

Biggest family

The prize for most unwieldy family reunions goes to … Saltidicae! This group, better known as the jumping spiders, includes more than 6,000 individual species. Jumping spiders are a fascinating bunch. They have the best vision of any spiders and often put on fantastic mating displays, complete with snazzy dances. One fuzzy little jumping spider in England even learned to jump on command.

Most star-studded names

They'll never know it, but a group of "smiley-face spiders" found in the Caribbean now boasts star-studded monikers.

Researchers and students at the University of Vermont gave six new species of Spintharus spiders names to honor those who had stood up for human rights and warned about climate change. These spiders are known for their distinctive markings, which look a bit like a happy face. The arachnid-honored individuals? Figure them out from these scientific names: Spintharus davidattenboroughi, S. barackobamai, S. michelleobamaae, S. davidbowiei, S. leonardodicaprioi, and S. berniesandersi. (The researchers also named one species, Spintharus skelly, after a pet cat.)

Largest web

The Darwin's bark spider (Caerostris darwini) spins its webs across rivers, ponds and lakes, trawling for the insects that flutter over water. By necessity, these webs can be huge — up to 30 square feet (2.8 square meters) in area and some 82 feet (25 m) across. That's a lot of work for a little spider: Females measure about an inch (2.5 cm) in body length, and males just a quarter of an inch (6 millimeters).

The webs are also extremely tough and elastic, researchers have found. A 2010 study revealed that the spider's silk is about twice as stretchy as other related spiders that spin smaller webs. It was also 10 times more resistant than Kevlar to breaking from being stretched.

Longest leg span

Heteropoda maxima, the giant huntsman, is sometimes considered the largest spider on Earth. These spiders, found in Laos, are more spindly than the Goliath bird-eater, but regularly boast leg spans of at least a foot (30 cm). This dinner-plate-sized arachnid doesn't spin webs; instead, it chases down its prey, delivering a venomous killing bite. Fortunately, the venom isn't very dangerous to humans, causing only minor pain and swelling.

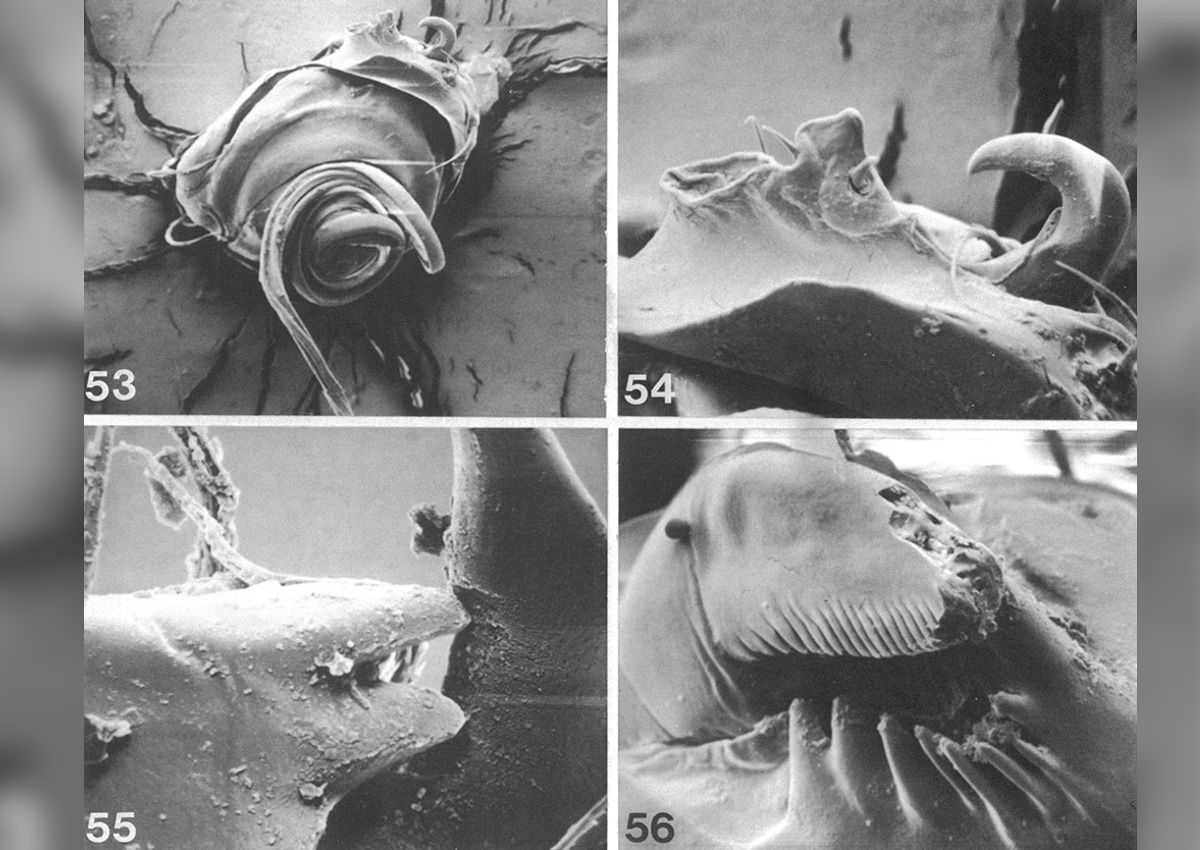

Smallest spider

A little less terrifying than the bird-eater or the huntsman is Patu digua, the smallest spider on record. This pipsqueak is only 0.01 inches (0.37 millimeters) in total length, according to a 1977 paper in American Museum Novitates. The spiders are so small that studying them is a challenge, according to that paper. A light microscope isn't strong enough to allow researchers to see their most diminutive features, so scanning electron microscopy must be used instead.

Longest fangs

The longest fangs-to-body-size award goes to Myrmarachne spiders. Remember the Salticidae jumping spiders and their enormous family tree? Well, Myrmarachne occupy one of the weirder branches. These spiders look almost exactly like ants, an adaptation that helps them avoid spider-loving predators. Male Myrmarachne spiders also have enormous fangs, longer than their head and thorax put together.

Largest venom glands

Most spiders have some form of venom, but very few are actually dangerous to humans; spider venom is generally injected in tiny amounts into insects or other small prey, so hurting people isn't the point. The Phoneutria genus of Brazilian wandering spiders is an exception. Their venom is capable of killing a human, in part because their large venom glands pack a lot of punch. Their venom glands can be up to 0.4 inches (10.2 mm) by 0.1 inches (2.6 mm) in size. But wandering spiders don't typically inject all their venom at one time, so the chance that a bite will actually kill a person is low.

Heaviest spider

With a common name like the Goliath bird-eater, it's no surprise that Theraphosa blondi weighs in as the most massive spider on the planet. These spiders have been known to grow as large as 6 ounces (170 grams), with a leg span up to 1 foot (30 cm) and bodies the size of a clenched fist. Goliath bird-eaters are capable of eating birds, but since they hunt mostly on the ground, their main prey are large earthworms — though they'll chow down on frogs and insects, too.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.